Morality.

It’s a tricky one.

So many connotations – good and bad.

I reckon morality’s a good thing.

I think it’s useful.

Essential, even.

Morality, in my view, is the greatest, most enabling invention humanity ever made. Or, if not the greatest, then a close second to the development of language.

Greater than the invention of fire. Or the wheel.

You think that’s an extreme claim?

Stay with me. I’ll explain.

What morality is not

Lots of stuff pretends to be morality but isn’t. Stuff like prurience, or ‘good manners, politeness or etiquette. Lists of rules from religions, traditions, or miscellaneous ideologies.

But morality is not a religion, a tradition, or an ideology. These things are often just ways to reinforce hierarchies of power:

“Behave the way I tell you to behave.”

“Do not steal (because all of this is mine).”

“That’s not how you should speak to your betters.”

“Know your place.”

“Honour thy father.”

“Show some respect.”

Essential characteristics

Morality, as distinct from your run-of-the-mill societal norms, has a range of characteristics which make it stand out as different – as something unusual and unique.

I’ll list a few:

???? Morality is universal

???? Morality is rational

???? Morality presupposes sentience

???? Morality requires us to be free

???? Morality needs a compelling source of authority

???? Morality is singular – there’s only one

???? Morality defines what’s right or wrong

With any of these characteristics missing, whatever you’re claiming is morality isn’t morality, it’s something else entirely.

I’ll tell you why.

Essential characteristic 1: Morality is universal

If you take a look at the way we use moral language, the way we talk about what’s good or bad, you’ll quickly notice that morality isn’t just for me, here, in one location. It’s for you, too, wherever you are.

How could it be otherwise?

No one honestly believes that morality changes when you move some arbitrary distance on a map. 10 metres? 100? 1,000? 10,000? Where’s the cut-off point? If it changes at 10,000 metres away, why shouldn’t it change a metre away?

The ordinary use of moral language implies that when you cross a border what was right and wrong on the side you’ve left behind still applies.

Slavery, for example, is universally wrong – not just here and now but in any culture, at any time. If you said, “Slavery is not ok here, but it was ok there,” then what you’re saying isn’t moral. It’s just an expression of preference or resignation.

Choose any border you like – national, cultural, civilisational or just the border between you and I – and morality transcends that border.

When morality says, “This is what you ought to do” or “This is how you should behave” the you isn’t just you. It’s everyone.

Just watch yourself when you’re observing that something’s good or bad. If you’re making a local claim then you’re not really talking about morality. You’re talking about a local custom or tradition or law. Non-universal judgements are not moral judgements, they’re just assertions of local norms.

Essential characteristic 2: Morality is rational

Like science, morality has to be coherent: consistent, logical, rational.

Why?

Because if you’re illogical or inconsistent anyone can say, “You’re inconsistent in what you say and do, so why shouldn’t I be, too?” They can say, “Why can’t I inconsistently call something moral one day but not the next?”

That’s the problem with inconsistency. It leaves convenient loopholes, out of which hypocrisy and conflict emerge.

Inconsistency allows us to say, “Why shouldn’t something be moral over there but not over here?”

If it’s inherent to the concept of morality that it has to be universal, then it has to be consistent and rational, too.

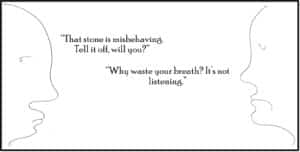

Essential characteristic 3: Morality presupposes sentience

A prerequisite for moral responsibility is that you must be able to understand what morality is asking you to do.

We don’t need to review the way people talk to see this. It’s right there in the concept.

It would be conceptually ridiculous to ask a stone to be moral, or an insect, or a tree.

A person or being needs to be conscious to be held morally responsible for the decisions they make, the actions they take.

We have to have minds to be moral. Mindless things just don’t get morality.

Essential characteristic 4: Morality requires us to be free

A hammer can be used to mostly hammer nails but occasionally hammer heads.

No one says, “Wicked hammer! Why did you hammer that head?”

Morality doesn’t apply to unfree stuff.

Morality applies to agency: not to the hammer but to the person who holds it.

This is similar to the requirement for sentience. Morality doesn’t apply to robots, machines, artefacts or tools. It doesn’t apply to amoebae or insects or fish or birds.

The concept of morality presupposes the creature it applies to is a free agent, an autonomous sentient who can choose to do right or wrong.

This has an important implication. It means that anything which reduces our ability to be moral, to make moral choices, is immoral. It means that freedom is not just a structural requirement for morality – it’s a fundamental moral right.

And it also means you can’t force someone to be moral. It means coercion is immoral. Reducing someone’s freedom limits their ability to make choices, including moral ones. And to stop someone from being able to make moral choices? What else could that be but immoral?

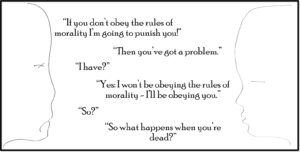

Essential characteristic 5: Morality needs a compelling source of authority

Morality needs a convincing ‘because’ behind the ‘ought’: a reason to be good; a ‘moral imperative’.

“Why ought I?” or “Why must I?” are questions morality has to be able to answer.

If you say, “Universally, across the board, X or Y is wrong,” then you need to have something universal to back you up. And that something has to be more authoritative than one person’s epiphany or another’s cultural norm.

People have tackled this problem by laying claim to intangible powers: ‘Gods A, B or C’, ‘prophets One, Two or Three’, the words of ancient sages or modern cults, a ‘divine purpose’, an ‘intelligent design’, ‘human nature’, ‘the historical imperative’, ‘economic necessity’, ‘the power of love’…

All these suggestions are entirely valid in their intention, since for morality’s ought to have any power we need that because – and it must be a because that is able to convince us, to gain our commitment, to gain our willingness to recognise its authority, and to place it above random impulse or selfish whim.

However, these answers aren’t good enough. Gods and cults and interpretations of human nature or history come and go, but morality continues on. If it needs a source of authority, then it needs a source of authority that is no less universal than itself.

I’ll take a look at what a rational, contemporary, and universal source of moral authority might be in the third article in this series.

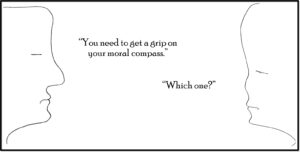

Essential characteristic 6: morality is singular

This is an important characteristic of morality.

No one says, “That’s how moralities tell us how to behave.”

No one says, “Do one of the right things.”

They say, “Do the right thing.”

No one offers you a choice of moral compasses. There’s only one: the universal, rational, authoritative and singular compass of morality.

If morality were plural, and you could have your morality and I could have mine, then morality as a concept would become meaningless. I couldn’t say that anyone – even a serial killer – was bad or should stop their killing spree, because they could always answer, “Why should I? It’s not wrong. It’s not immoral. Not according to my morality.”

Essential characteristic 7: morality defines what’s good or bad

Morality is the measure by which we assess all autonomous sentient behaviour.

Traditions, religions, politics, culture – they don’t outrank morality; they’re all open to moral assessment.

Morality sits outside physical borders, cultural borders, even civilisational borders.

It’s allows you to assess the activity of any group or collective, as if you’re on the outside, looking in.

This aspect of your community, tribe, or civilisation is moral. That aspect? Not so much.

Morality tells us what’s good, what’s bad, what anyone should do, what everyone shouldn’t. And what morality says is not random. It’s at least partly determined by the essential characteristics of morality that we’ve identified here.

But what is morality for?

We’ve looked at what morality IS – it’s shape and form.

Morality is rational, universal, singular, and presupposes freedom and sentience. But can we stop there?

Do we really understand morality with just a list of its characteristics, a description of its parts? A car is not ‘windows, wheels, a motor, and wipers’. We don’t really understand what a car is if that’s all we know. A car is for something. It has a purpose, a function. If you don’t know that a car is for carrying people from place A to place B, you don’t really understand what ‘a car’ means.

So what about morality? What is its function? What is morality FOR?

In my next article in this series, published on Dorset Eye tomorrow, I’ll attempt to answer this incredibly important question.

Luke Andreski

Luke Andreski is a founding member of the @EthicalRenewal and Ethical Intelligence collectives. His books include Intelligent Ethics (2019), Ethical Intelligence (2019), Short Conversations: During The Plague (2020) and Short Conversations: During the Storm (2021).

Intelligent Ethics is available here.

You can connect with Luke on LinkedIn, https://uk.linkedin.com/in/luke-andreski-ethics, or via @EthicalRenewal on Twitter https://twitter.com/EthicalRenewal

With thanks to Gigiextremeno for the delightful ring-tailed lemur image, CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Join us in helping to bring reality and decency back by SUBSCRIBING to our Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQ1Ll1ylCg8U19AhNl-NoTg and SUPPORTING US where you can: Award Winning Independent Citizen Media Needs Your Help. PLEASE SUPPORT US FOR JUST £2 A MONTH https://dorseteye.com/donate/