Former Shadow Minister Christ Williamson explains why the small rise in the minimum wage will not remove the poor from poverty, whilst reminding us that the UK economy could a lot more.

THOUGHT FOR THE DAY

— Chris Williamson (@DerbyChrisW) November 3, 2024

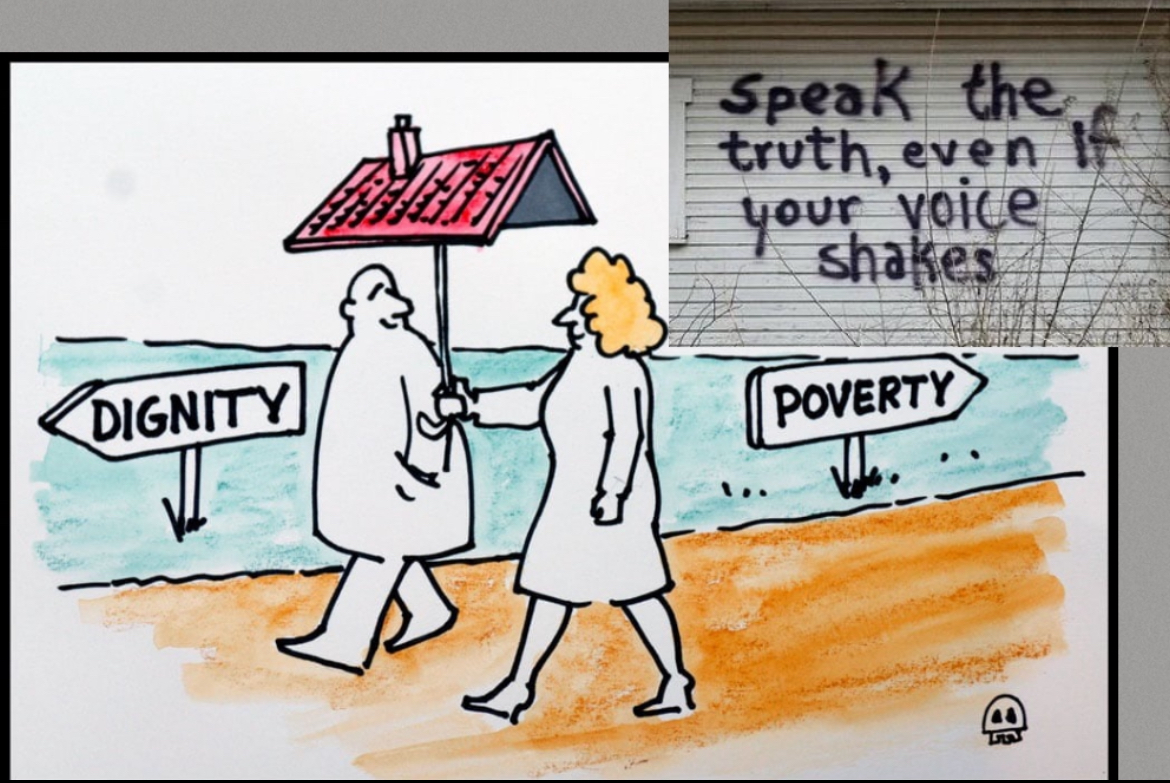

Poverty pay in the world's sixth biggest economy is totally unjustifiable, yet the increase in the minimum wage won't lift the lowest paid workers out of poverty. pic.twitter.com/AAZaGmOp4P

The Awful Truth Revealed

Poverty persists in the world not because of a lack of resources or because humanity is inherently incapable of addressing it. Rather, poverty exists within a system that has built-in mechanisms to maintain it. Many believe that capitalism, the dominant economic system, provides pathways to upward mobility, even for those at the bottom. After all, the notion of “rags to riches” is celebrated in capitalist societies. Yet, despite decades of technological advancement, increases in production, and wealth accumulation, poverty remains as entrenched as ever. Indeed, for all its promises, capitalism cannot eliminate poverty.

For those unfamiliar with economic theory, capitalism can appear to be an economic model that encourages competition and rewards hard work. Theoretically, the capitalist market should allow everyone to compete and prosper. Yet, in practice, the concentration of wealth in the hands of a few continues to grow. The 2022 Oxfam report revealed that the wealthiest 1% had pocketed almost twice as much wealth as the rest of the world combined during the COVID-19 pandemic. The average worker, meanwhile, struggles to make ends meet, faced with stagnating wages, rising costs, and dwindling social services.

Capitalism, fundamentally, is a system that requires inequality. Its champions, such as Adam Smith and later economists, acknowledged that capitalism relies on competition and profit maximisation. However, this profit does not benefit all equally; it accumulates with those who own the means of production, the capitalists, while the workers receive only a fraction. This unequal distribution is not a flaw in the system but a feature, necessary to incentivise labour and maximise productivity. But here lies a contradiction: if the goal of a system is to generate profit, then reducing poverty and raising the incomes of the poorest undermines the very basis of profit-making.

It’s here that we must ask: Do our political leaders know this? Of course they do. In Britain, the Labour and Conservative parties alike, while rhetorically sympathetic to the plight of the poor, operate within the same economic framework. Both parties benefit from maintaining the system as it is. The establishment, regardless of its political leaning, relies on the stability and predictability that capitalism provides. Radical measures that could genuinely eradicate poverty are unlikely to be proposed, let alone implemented, because they would disrupt the flow of wealth to those at the top.

The notion that politicians will do nothing substantive about poverty may sound cynical, but examples bear it out. Consider austerity policies introduced by the Conservative government after the 2008 financial crisis. These cuts were justified as necessary to reduce national debt, but in reality, they disproportionately affected the poorest communities. Public services were slashed, benefits cut, and support systems dismantled, all while the wealthy saw their tax rates stabilise or decrease. This was not a random occurrence; it was an intentional decision to protect capital interests by shifting the burden onto those least equipped to bear it.

Even Labour, often seen as a champion for working people, has failed to offer a genuine alternative. Tony Blair’s New Labour platform in the 1990s embraced neoliberal policies, deregulating the financial sector and allowing the unchecked expansion of private enterprise. Blair famously declared, “We are all middle class now,” as if the structural barriers to upward mobility had magically disappeared. In reality, by the end of his government, inequality had increased, as had reliance on precarious, low-wage jobs. The hope for a “Third Way” between capitalism and socialism proved to be little more than a rebranding exercise, allowing Labour to appear progressive while reinforcing the very structures that kept people poor.

To examine why capitalism cannot solve poverty, we need to look at the motivations that drive the system. In a capitalist economy, corporations are designed to maximise profit, and this objective inherently contradicts the goal of poverty alleviation. Profit is generated by minimising costs, which often means paying workers as little as possible. If companies are forced to increase wages significantly, their profit margins shrink, and this is something capitalists, and the politicians they lobby, actively resist. Companies outsource jobs to countries where labour is cheap, pressuring even wealthier nations to lower wages and reduce benefits to remain “competitive.” This constant race to the bottom keeps wages suppressed and workers in a state of financial precarity.

Take the case of Amazon, one of the world’s most profitable companies. While CEO Jeff Bezos accumulated billions, many of Amazon’s warehouse workers struggle to survive on minimum wage, working under grueling conditions with limited benefits. In the UK, Amazon has resisted unionisation efforts and has consistently underpaid its workers, despite being worth hundreds of billions. Capitalist logic dictates that reducing worker pay boosts profits, and thus, companies like Amazon are incentivised to perpetuate poverty, not eliminate it. This is not an aberration; it is the system working as designed.

Some might argue that progressive taxation or corporate responsibility initiatives could address these issues within a capitalist framework. However, history shows that these measures are often superficial at best. In the UK, large corporations routinely evade taxes through legal loopholes and offshore accounts. In 2020, an investigation by The Guardian revealed that several of the UK’s wealthiest individuals and corporations had paid little to no tax over the previous decade. This revenue could have funded social programmes to alleviate poverty, but instead, it remained in private hands, protected by policies enacted by successive governments.

One could argue that the solution lies in increasing social mobility, providing education, and creating opportunities. But the statistics tell a different story. Despite widespread access to education, those born into poverty remain disproportionately represented among the poor. In the UK, the Sutton Trust reported that only one in eight children from disadvantaged backgrounds would achieve professional careers, while nearly half of those from wealthier backgrounds would. The notion that hard work and education alone are enough to rise out of poverty ignores the structural barriers that keep the poor in their place.

The political establishment is well aware of these realities. It’s not that they lack insight or that they are simply ineffective. Rather, they are complicit in maintaining the system. To truly address poverty, politicians would need to challenge the foundations of capitalism itself; a move that would alienate their wealthiest supporters, risk market instability, and disrupt the established order. Consequently, they offer limited reforms, such as slight increases to the minimum wage or incremental welfare adjustments, which are often inadequate to meet the needs of the poorest.

This brings us to the heart of the issue: poverty cannot be cured within a capitalist framework because capitalism is predicated on inequality. Capitalism needs a “reserve army” of unemployed or low-wage workers to maintain a flexible labour market. This surplus of labour keeps wages low and ensures that there is always someone willing to work for less, pressuring employed workers to accept lower wages and fewer benefits to avoid losing their jobs. Karl Marx, one of capitalism’s earliest critics, described this phenomenon well, explaining that “accumulation of wealth at one pole” is accompanied by the “accumulation of misery, agony of toil, slavery, ignorance, brutality, [and] mental degradation at the opposite pole.”

Even the few politicians who occasionally discuss wealth redistribution or raising taxes on the rich often do so in a way that is palatable to the capitalist class. They suggest minor adjustments, framing their proposals as beneficial for everyone, including corporations. Real measures that could disrupt wealth concentration—such as substantial taxes on capital gains, caps on CEO pay, or strict limits on profit distribution, are rarely considered, as they would fundamentally alter the mechanics of the market.

There is a long history of political figures acknowledging these realities, often with surprising candour. In 1967, American civil rights leader Dr Martin Luther King Jr remarked, “We must recognise that we can’t solve our problem now until there is a radical redistribution of economic and political power.” King understood that poverty was not simply an unfortunate byproduct of capitalism but a requirement. For those in power, any suggestion of “radical redistribution” is dangerous, as it threatens the structures that uphold their influence and wealth.

So, why won’t establishment political parties tackle poverty head-on? The answer lies in the mutual dependence between the political elite and the wealthy. Elections are expensive, and in most capitalist societies, campaign financing is heavily influenced by wealthy individuals and corporations. Politicians rely on these entities for funding, and in return, they align their policies to favour capital interests. This is evident in the way political lobbying shapes legislation. In the UK, numerous MPs have ties to corporations, serve on corporate boards, or receive donations from business magnates. Consequently, policies that could genuinely address poverty are unlikely to gain traction, as they would upset the very interests that finance political careers.

Moreover, capitalism’s influence extends beyond just political financing. The media, largely owned by wealthy individuals or corporations, shapes public perception, often framing poverty as a failure of the individual rather than a systemic issue. This narrative supports the capitalist ideal: if poverty is the result of laziness or poor choices, then there’s no need to change the system; only to encourage people to work harder. It’s a convenient story, but it ignores the structural forces at play, allowing the wealthy to escape responsibility for the system that sustains their wealth.

Despite the evidence, some people still believe that capitalism can be reformed to end poverty. They argue that incremental changes, such as universal basic income or enhanced welfare, will address the issue. Yet these measures, while potentially beneficial, do not resolve the fundamental contradiction of capitalism. As long as profit is the ultimate goal, and wealth accumulates in the hands of a few, poverty will persist. Wealth redistribution on a significant scale is incompatible with capitalism as we know it, and so these efforts remain limited in scope, offering temporary relief rather than long-term solutions.

In summary, poverty is not an accident or an unfortunate consequence of capitalism; it is a systemic necessity. Political leaders, whether they are declared ‘left’ or ‘right’, remain tethered to the mechanisms of capitalism, aware that to dismantle the structures that create poverty would mean undermining the very system that supports their power. For them, poverty serves a purpose: it provides a steady labour force, keeps wages down, and allows the accumulation of profit to continue unabated.