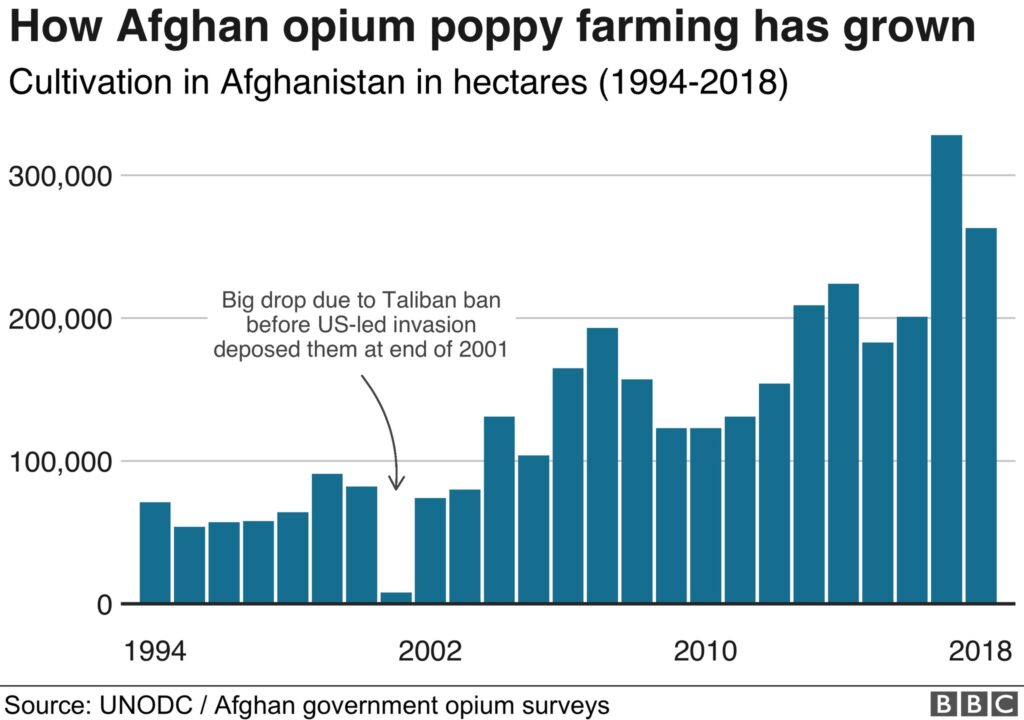

The Taliban banned production of the poppy in 2000. After twenty years of war, Afghanistan is now responsible for 82% of the world’s opium supply.

Before the U.S. invaded Afghanistan in 2001, around 82,000 hectares of Afghanistan cultivated poppy, the plant that produces opium which can be turned into heroin and other opiates. United Nations and U.S. estimates put the current poppy crop at around 224,000 hectares. According to the UN, that number is up 37 percent from 2019. The U.S. spent $8 billion trying to eradicate the plant in Afghanistan only to watch as it became the most profitable crop the country produced. Afghanistan now produces 82 percent of the world’s supply, according to the UN.

According to a 2018 SIGAR study of poppy cultivation in Afghanistan, the U.S. lacked a clear understanding of the plant and what it meant to the farmers who grew it. And, like so many other issues in Afghanistan, the strategy around how to handle the plant constantly changed. “Our analysis reveals that no counternarcotics program led to lasting reductions in poppy cultivation or opium production,” SIGAR said. “Eradication efforts had no lasting impact, and eradication was not consistently conducted in the same geographic locations as development assistance. Alternative development programs were often too short-term, failed to provide sustainable alternatives to poppy, and sometimes even contributed to poppy production.”

Emblematic of the failure is a clip of Geraldo Rivera on Fox News interviewing a Marine in the early days of the war that regularly circulates online. In the clip, a soldier explains to Rivera why he is guarding a farmer’s poppy fields, and why farmers there are more interested in growing poppy than cucumbers or watermelon like the U.S. wanted them to.“We are tolerating the cultivation of the opium because we know that if we were to destroy it now, the population would turn against the Marines and it would be a real security risk,” Rivera said.

Poppy cultivation exploded after the invasion and it was good business for Afghans. According to SIGAR, by 2017 “poppy cultivation alone was estimated to provide up to 590,000 full-time equivalent jobs, more than the number of people employed by the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces.”

Conditions in the U.S. and Europe laid the groundwork for an incredible demand for opium. The booming sale of opiates like hydrocodone, fentanyl, and oxycontin created new opium customers. When people lost prescriptions or wanted a bigger high, they turned to heroin and Afghanistan’s poppy fields were ready to meet the demand. If someone buys heroin in Russia or Europe, there’s a good chance it came from a poppy plant in Afghanistan. SIGAR also estimated that 90 percent of heroin seized in Canada came from Afghan poppies.

A few years into the war, the U.S. began to attempt counternarcotics initiatives and discovered that many of its Afghan allies were involved in the trade. Everyone was making so much money there was no incentive for Afghans to work with the Americans to eliminate the plant. In 2005, DEA and Afghan police pulled 9 metric tons of opium out of the offices of the then governor of Helmand Province.

As American troops began to leave, the DEA and international partners began to lose interest in counternarcotics in the country. Afghanistan was too complicated, and American strategy there too inconsistent to get anything done. In one province, aid workers would be bribing landowners into growing soybeans while one province over Marines were launching precision strikes on production facilities.

America’s war in Afghanistan was a tragedy that set the perfect conditions for an explosion in opium production. “As we look back at our misadventure in Afghanistan it’s important to understand that there are second and third order effects to an invasion,” Grazier said. “This is another great cautionary tale about why we need to do absolutely everything possible to avoid these kinds of conflict in the future.”

The future of the poppy in Afghanistan is unknown. Seeking a normalization of relations with the rest of the world in 2000, Taliban banned cultivation of the plant outright. Just like when the U.S. went to war against the poppy, the Taliban faced opposition from Afghan farmers after the ban. Also, during the twenty years of U.S. occupation, the Taliban learned the value of the drug as both a means of quick cash. The Taliban understands Afghanistan better than the U.S. ever did and it knows that banning the crop will hurt people in the rural provinces.

Source: https://www.vicemediagroup.com/

Join us in helping to bring reality and decency back by SUBSCRIBING to our Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQ1Ll1ylCg8U19AhNl-NoTg and SUPPORTING US where you can: Award Winning Independent Citizen Media Needs Your Help. PLEASE SUPPORT US FOR JUST £2 A MONTH https://dorseteye.com/donate/