The alarming rise in the number of prisoners being accidentally released is more than a simple administrative error; it is a stark symptom of a prison service stretched to breaking point. A deep dive into the latest figures reveals a system buckling under the combined pressures of long-term austerity, chronic staffing issues, and the complex challenges of a part-privatised service.

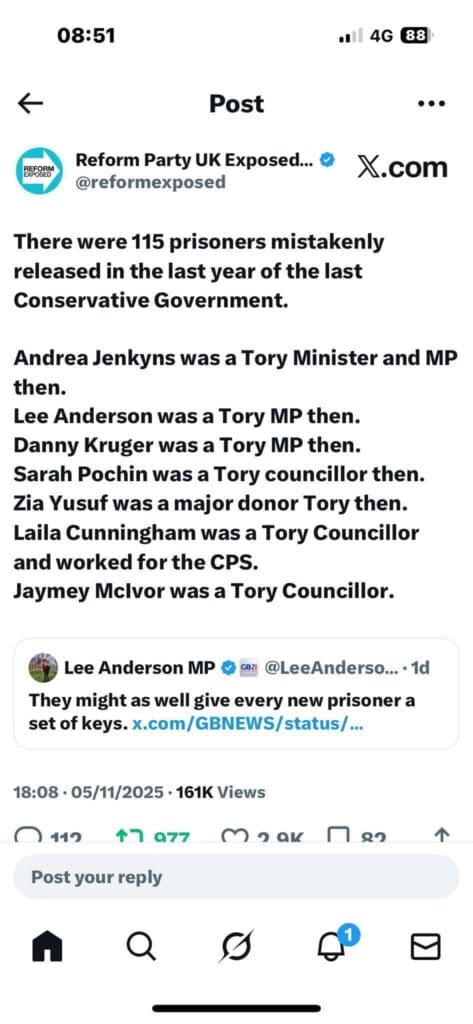

The statistics are startling. In the 12 months to March 2025, 262 prisoners were accidentally released, a dramatic increase from 115 the previous year. To put this into perspective, while the overall number of releases rose by about 13%, the number of errors more than doubled. This disproportionate surge suggests a system where procedures are failing at a rate that far outpaces its growing workload. The problem is widespread, with 72 of the 121 prisons across England and Wales releasing at least one prisoner by mistake.

The examples are stark. Pentonville Prison in London, for instance, accidentally released 16 prisoners in 2024-25, up from six the year before. For a prison with a population of just under 1,200, this is equivalent to mistakenly letting out more than one in every 100 inmates. Furthermore, the issue is not confined to prison gates; around one in 10 erroneous releases occurred from “escort areas”—zones managed by private contractors responsible for transporting prisoners between courts, jails, and immigration centres.

The Human Factor: A Demoralised and Depleted Workforce

Beneath these alarming figures lies a deep-seated staffing crisis. While overall staff numbers are higher than in some previous years, the service is haemorrhaging experienced personnel. In the year to June 2025, nearly 13% of staff left the prison service, a turnover rate almost twice that of the wider Civil Service. Most concerningly, half of those who left had been in the job for a year or less, indicating a struggle to retain new recruits.

Those who remain are under immense strain. Prison staff missed an average of 12 days of work due to sickness in the same period, with two in five absences related to mental health issues. This is three times the national average for UK workers. This combination of high turnover and high sickness rates creates a perfect storm: an inexperienced, overstretched workforce operating in a high-stakes environment where fatigue and understaffing directly compromise public safety.

The Funding Chasm: Austerity’s Long Shadow

This operational meltdown has prompted renewed questions about government funding. As former Conservative justice secretary Alex Chalk highlighted, the Ministry of Justice (MoJ)—responsible for prisons, probation, courts, and legal aid—has a budget that pales in comparison to other departments.

This financial squeeze is not new. According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the MoJ is expected to be 5.6% smaller than it was in 2010 by the end of the current parliament, a testament to over a decade of austerity. This long-term reduction in real-terms funding has forced the service to do more with less, leading to heavier workloads, lower pay relative to the private sector, and an over-reliance on often costly agency staff.

The consequences of this underfunding are now impossible to ignore. The accidental release of prisoners is one of the most serious failures a justice system can make, representing a direct threat to public confidence and safety. It is the clearest indicator yet that years of austerity, combined with the operational fragilities of a fragmented system, have pushed the prison service to its limit. Without a significant reinvestment in both its infrastructure and, most importantly, its people, these critical errors are likely to become an ever more frequent feature of a service in perpetual crisis.