Hilary and I just got back from Northern Ireland where we spent the week with family and close friends. While we were driving up to the north coast with the children Hilary let out a howl like a wounded animal. “No! David Graeber is dead.” She had been on Twitter and come across the terrible news from his wife – love and collaborator, artist Nika Dubrovsky. I swerved, I disbelieved, I hoped it was all wrong as I gripped the wheel, wondering what had happened.

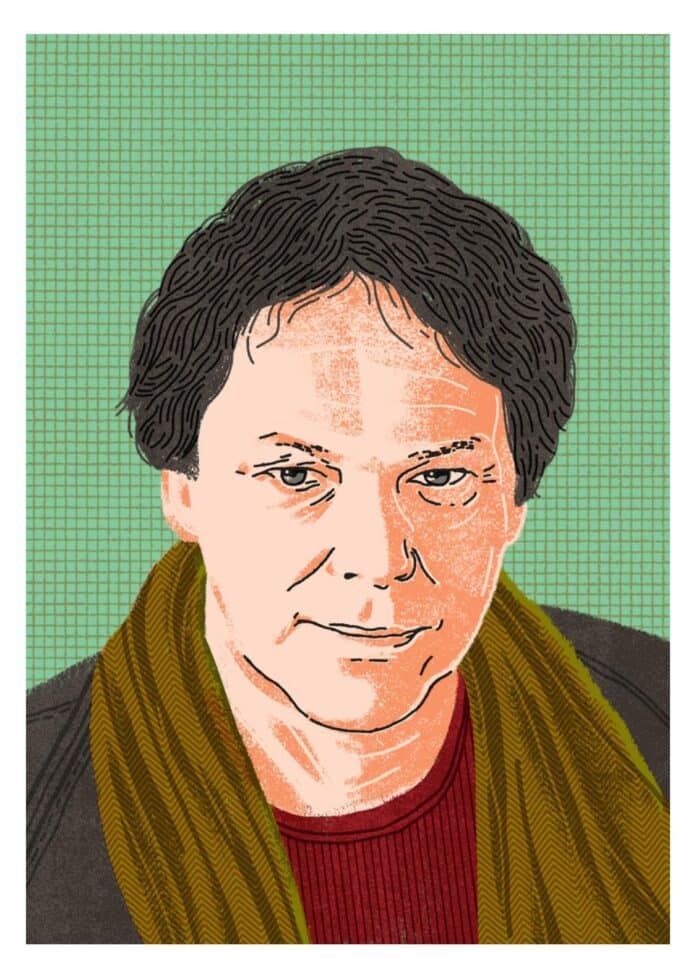

When I first met David Graeber, it was in much the same way as I met Tolstoy, George Orwell or Aristotle – words on the pages of one of his books: Debt The First 5000 Years. The difference was that he was alive – but to me he took on the majestic proportions of those other writers. Graeber was an anthropologist who had moved to England after losing his post at Yale – most people agree that this was due to his political activities (he was one of the most prominent thinkers in the Occupy movement). Despite huge academic success, Graeber could find no new postings in the US post Yale but was inundated with offers from universities overseas, and subsequently moved to London – first working at Goldsmiths (2007-13) and then offered a professorship at LSE (2013-20)

His book about debt was recommended to me soon after I learned about Strike Debt, who had been buying up and abolishing millions of dollars of student and medical debt. I hadn’t expected the literary treasure within, I sorted through revelations like jewels, I sent copies to friends around the world. Graeber – and Andrew Ross – two writers who I will always associate, were responsible for fundamentally changing the way I understood history, economics and philosophy.

As Roald Dahl writes in ‘Matilda’ –“authors ..[send].. their books out into the world like ships on the sea” – where they end up and what actions they inspire and provoke is beyond their control. This book had found its way into my hands, and through that into my mind and heart. The words on the page contain the infectious spirit of rebellion and of hope changing our minds, hearts and our understanding of the world around us forever.

If there had been a straightforward way to adapt Graeber’s book into a film, I would have done it – but like Charlie Kaufman’s attempt to adapt a technical book about orchids in ‘Adaptation’ – it wasn’t quite possible despite my best attempts to bring the stories and images it contained to life in a scrapyard in Purfleet. However, Graeber’s book has brought to life a film and an outpouring of joyous rebellion in a community in Walthamstow – years after its publication.

When he came to visit the bank in Walthamstow he was clearly very moved. His father had been a printer, and the smell of the inks, and the sight of the drying banknotes affected him. Perhaps too, he recognised the impact of his philosophical ideas on a community, something that as an author he could not possibly have predicted. We were so delighted to see him here, inside an artwork – It was like glimpsing Lewis Carrol wandering through Wonderland.

We arrived at the beach in Port Stewart. Our children ran out onto the sand. The sky was dark and filled with swirling wind and rain. Our hearts were shot through and bewildered by the news. We went through the motions of a day at the beach – everything was exquisitely tragic, messages came in – friends wrote to us, more information cascaded. Venice. Totally unexpected. Mysterious illness. I held Hilary’s hand – she wrote his name in the sand as defiant monument to impermanence and moments later as I tried to photograph it, the letters were already blowing away.

Through these last few years in Britain and America we’ve lived through Trump, Johnson, Farage and all these terrible nouveau Fascists, we’ve experienced hope in Corbyn and McDonnell, only for it to be shot down amid shameful smears from the centre right. Graeber played such an important part for us in the movement to refuse these people – he has played a huge role in helping us to formulate our hopes to resist. His steady brilliance, his anarchism mixed with his authority as a professor of anthropology at LSE gave us a champion we could rally around. His willingness to enter the fray on Twitter and his ability to articulate what so many of us felt with clarity, wit and economy. More than anything Graeber was a lighthouse – he threw his beam out across hypocrisy, double-speak and sheer hot air, illuminating the world – and thereby, our lives in a totally unique way.

Towards the end of his book Debt – Graeber writes that he believes that over the last three to four decades there has been a sustained attempt to create an atmosphere of total hopelessness, leading people to paralysis and despair, removing all agency to change things for the better.

“Hopelessness isn’t natural. It needs to be produced. To understand this situation, we have to realize that the last 30 years have seen the construction of a vast bureaucratic apparatus that creates and maintains hopelessness. At the root of this machine is global leaders’ obsession with ensuring that social movements do not appear to grow or flourish, that those who challenge existing power arrangements are never perceived to win. Maintaining this illusion requires armies, prisons, police and private security firms to create a pervasive climate of fear, jingoistic conformity and despair. All these guns, surveillance cameras and propaganda engines are extraordinarily expensive and produce nothing – they’re economic deadweights that are dragging the entire capitalist system down.”

But if Graeber’s life illustrates anything, it’s that a life of action and imagination is possible, even amid these very dark and apparently hopeless times. Hopelessness is manufactured. And there’s a strange machine churning it out.

Seeing the tributes and obituaries pouring in across the internet reminds us of the loss, but it also moves us to a feeling of thankfulness. We’re lucky to have had David Graeber in this world, we’re lucky to have his books, his essays, his humour and intelligence. We’re lucky to have had his support, his mentorship. Like staring at a light before it goes off, we are left with a clear impression of the bulb, it shines on in our minds eye – but leaves us temporarily blinded too. And eventually you have to open your eyes and find yourself in a dark room.

To share a world view with someone is incredibly intimate. To have lived through the same disappointments, to have felt the same outrages….we’ve lost the person who could most coherently express the way we felt, who always showed up and did the work, the person who we could rely on to keep the fires of hope stocked with the fuel to keep them burning brightly.

Will the old divisions come back? Or will we take the hands of our friends, colleagues and distant cousins in the progressive movement? Will we all take a moment to share in the thought that life is so fleeting? Will we mend or even create bridges and find our way back to one another? Will we bury our hatchets on the left and come together to help the legacy of Graeber and the other great writers not only of the past – but of the future – and not just the great writers – the great campaigners, the great lawyers, the hopers and dreamers – the artists.. Could we use this devastating moment to reflect on the journey each of us has to look forward to – the journey towards our own ending? The ongoing fight for a better, happier and fairer world..?

While we search for the answers to these questions, we feel the jagged edges of loss. Since the news came, we have been reeling. We have felt challenged to honour his memory by raising our game and continuing despite all the difficulties, to create more work with meaning and passion in the very brief time we have. Coming ‘home’ for a few days, to the skies and shores of my childhood I find that the purpose of life remains fairly simple and straightforward. If Graeber’s death has anything good to offer us, shouldn’t it be in the all too painful reminder that we must all up our games, that for ever is only an illusion and that we are all briefly illuminated and we must shine and signal forth in a relay of beacons linking humanity across history.

Daniel Edelstyn