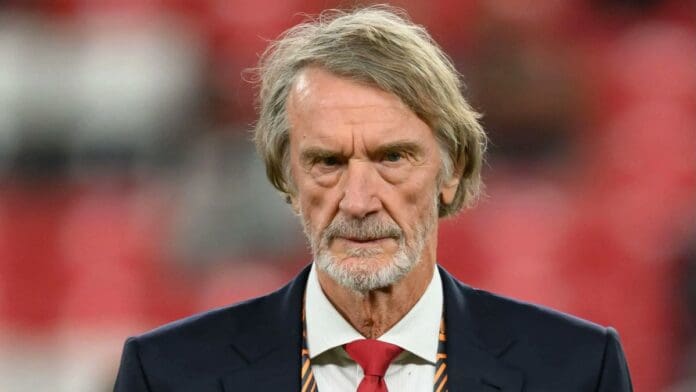

Sir Jim Ratcliffe’s claim that Britain has been “colonised” by immigrants is not just inflammatory rhetoric; it is a revealing glimpse into the mindset of a billionaire industrialist whose own wealth depends, quietly but fundamentally, on the very globalised labour and migration systems he now disparages.

The language matters. “Colonised” is not an economic term. It is a culture-war dog whistle, conjuring images of invasion and dispossession. Yet the numbers he cites do not even withstand basic scrutiny. The UK population was not 58 million in 2020; the Office for National Statistics puts it at around 67 million in mid-2020 and 70 million in mid-2024. The 58.9 million figure dates back to 2000. Compressing 24 years of demographic change into a four-year narrative of “colonisation” is not analysis; it is distortion.

But the deeper irony is this: Ratcliffe’s own business empire — INEOS — is built on global supply chains and cost-competitive labour markets. The chemical industry does not function in a sealed national bubble. It relies on migrant labour at multiple levels: from highly skilled engineers recruited internationally to the low-paid contractors, logistics workers, cleaners, security staff and agency labourers who keep plants running. Across Britain’s industrial estates and distribution networks, migrant workers are disproportionately represented in physically demanding, low-wage roles. They are not “draining resources”; they are producing value.

This is not unique to INEOS. It is the structural model of modern capitalism. Wealth at the top is frequently underpinned by low-paid labour at the bottom. Britain’s hospitality, care, agriculture, construction and logistics sectors, all of which support the lifestyles and investments of the ultra-wealthy, are heavily reliant on migrant workers. The same business class that demands labour flexibility, suppressed wage costs and frictionless trade cannot plausibly turn around and declare the human beings who make that system viable to be a form of “colonisation”.

Then there is Manchester United.

Ratcliffe speaks of making “difficult” and “unpopular” decisions at the club. Yet elite English football is itself one of the most globalised industries on earth. Manchester United’s first-team squad is overwhelmingly international. The Premier League as a whole has, for years, had a majority of non-UK players. That is not an accident; it is the consequence of market logic. Clubs scour the globe for talent because global recruitment increases quality and commercial reach. The league sells broadcasting rights to Asia, Africa and the Americas precisely because it is an international spectacle.

If Britain has been “colonised”, then so too, by that logic, has the Premier League. But no one in the boardrooms of Old Trafford, Stamford Bridge, or the Etihad is proposing a return to an all-English starting XI. Why? Because global talent wins matches and drives revenue. International stars expand shirt sales, sponsorship deals and media markets. Diversity in football is not framed as invasion; it is framed as competitive advantage.

The contradiction is glaring. In industry and sport, globalisation is celebrated when it enhances profit and prestige. In politics, it is condemned when it can be weaponised for populist appeal.

Ratcliffe also invokes the familiar trope of “nine million people on benefits”. This figure includes pensioners, disabled people and those in work receiving in-work support. It is not a simple headcount of able-bodied citizens “opting” not to work. In fact, the majority of working-age benefit claimants are either employed or medically assessed as unfit for work. Meanwhile, migrants are statistically more likely to be of working age and economically active. The fiscal picture is complex, but complexity rarely fits neatly into a soundbite.

There is, of course, a legitimate debate to be had about immigration levels, infrastructure strain and labour market policy. Rapid population growth can put pressure on housing, public services and wages at the lower end of the market if governments fail to invest properly. But those pressures are political choices about distribution and planning, not evidence of “colonisation”.

It is also worth noting that when billionaires speak of “unsurvivable conditions” for European industry, they are usually referring to energy prices, regulation, taxation and global competition. In other words: structural economic forces. Yet when discussing migration, structural analysis gives way to emotive simplification.

If courage is required, as Ratcliffe suggests, perhaps it lies not in scapegoating migrants but in confronting the economic model that keeps wages low while wealth concentrates at the top. Perhaps it lies in acknowledging that globalisation is not a buffet from which the powerful can select only the profitable elements. You cannot champion open markets for capital and closed borders for labour without exposing the hypocrisy at the heart of the argument.

Manchester United’s success, when it returns, will not be built on nostalgic nationalism. It will be built on international scouting networks, multinational sponsorship and a dressing room filled with players from across the globe. British industry, likewise, will not revive through rhetorical border walls but through investment, innovation and a labour force, domestic and migrant, that is paid fairly and treated with dignity.

If Britain faces profound challenges, they will not be solved by framing demographic change as invasion. They will be solved by honest accounting of who benefits from the current system and who quietly sustains it.

The uncomfortable truth is that the modern British economy, from petrochemicals to Premier League football, is already global. The question is not whether that reality exists. It is whether those at the top are prepared to acknowledge the human foundations on which their fortunes rest.