Colonisation is the process by which a country, group, or people settle in and establish control over another territory, often far from their original homeland. To argue that anyone other than rich and powerful people have done this in Britain is beyond ludicrous. Only ignorant racists would believe that.

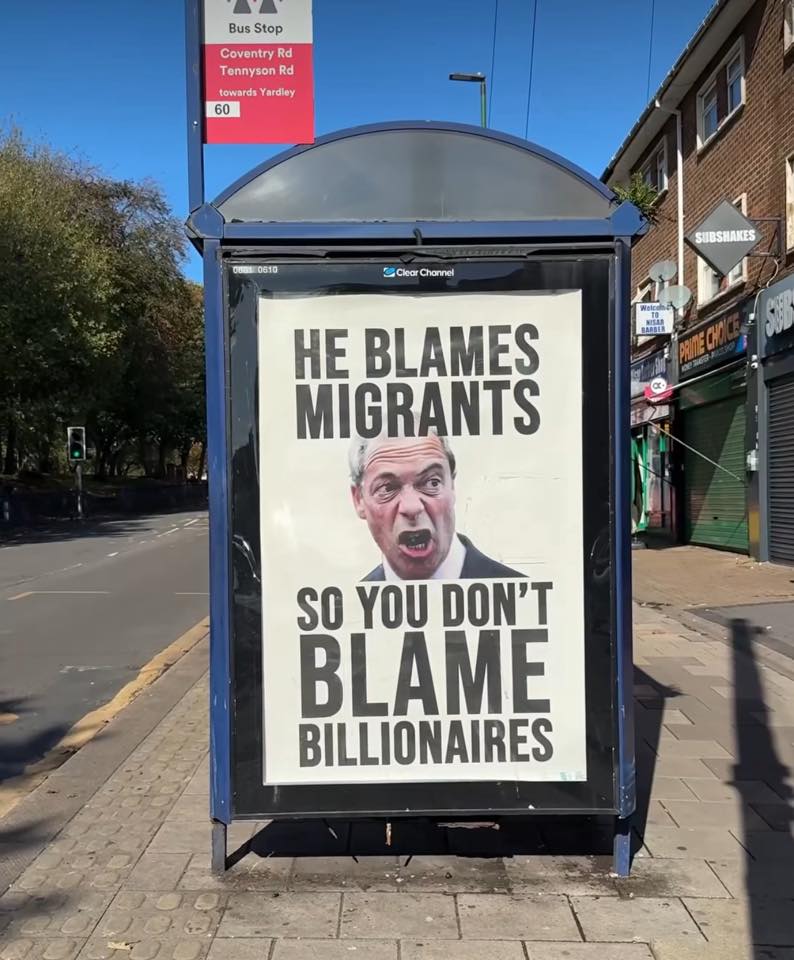

The reality is very different and those who tell you otherwise have an agenda to distract you from what has really happened.

The polite fiction is that Britain is an open, confident, global nation, attracting investment because it is stable, democratic and well-governed. The less comfortable truth is that it has become a showroom for global capital and a laboratory for elite power. The question is no longer whether foreign billionaires own large parts of Britain. It is why Britain was so deliberately redesigned to make that possible and who truly benefits from it.

The language of “colonisation” unsettles because it reverses the imperial gaze. Britain once exported power; now it imports capital and calls it strength. But ownership is power. When the most valuable postcodes in Kensington, Mayfair and Belgravia function less as neighbourhoods and more as safety deposit boxes in the sky, something has shifted. Once Hyde Park was not simply a luxury development. Now it is a signal flare announcing that London had been repurposed: from a city to live in to a vault in which wealth can sleep undisturbed.

The lights are often off because the purpose is not habitation. It is asset preservation. In sociological terms, housing has been detached from use value and inflated into pure exchange value. Homes are no longer primarily places of social reproduction, where families grow, communities form and identities root. They are instruments in a global portfolio. Meanwhile, those who actually work in the city are pushed further out, commuting longer distances to service wealth they will never touch.

This transformation did not happen accidentally. It was engineered. From the 1980s onwards, successive governments embraced privatisation, deregulation and the financialisation of everyday life as articles of faith. The “Big Bang” reforms in the City were celebrated as modernisation. In reality, they marked the consolidation of a new settlement: Britain would be governed as a marketplace first and a polity second. Nigel Farage and the Reform UK leadership are as much part of this as the other establishment political parties.

Non-dom tax status, investor visas and light-touch regulation were not oversights. They were invitations. The message was clear: bring your capital, and Britain will ask few questions. Opaque corporate structures could acquire land. Shell companies could park money in property. Political donations could flow through respectable channels. In return, the state gained short-term inflows and the illusion of prosperity.

The same logic reshaped cultural institutions. Football clubs such as Chelsea F.C., Manchester City F.C. and Newcastle United F.C. became vehicles not only for sporting success but also for geopolitical branding. Fans celebrate trophies, understandably, but the ownership structures embed clubs within global power networks. These are not merely businesses; they are civic symbols. When they answer to distant sovereign wealth funds or oligarchic fortunes, local accountability becomes ornamental.

Infrastructure tells an even starker story. Heathrow Airport, energy grids, water companies and rail franchises have all passed into complex webs of international ownership. In theory, this is simply globalisation at work. In practice, it diffuses responsibility. When bills rise or services fail, who answers? A multinational board? A foreign state-backed fund? The abstraction of ownership makes democratic control harder to exercise.

The deeper issue is not nationality. It is class power. British billionaires are hardly innocent bystanders; they too benefit from the same structures and own assets abroad. The system is transnational. Wealth circulates freely, while labour and community remain rooted and constrained. The elite, whether domestic or foreign, share more in common with one another than with the populations over which their capital flows.

What has emerged is a Britain bifurcated. On one side, a narrow stratum of asset-holders, global in outlook, mobile in residence, lightly taxed and politically connected. On the other hand, a majority whose wages have stagnated, whose housing costs soar and whose public services have been pared back in the name of fiscal prudence. The rhetoric of national sovereignty rings hollow when economic sovereignty has been quietly auctioned.

Critics are often told to be grateful. Foreign investment creates jobs. Regeneration projects revive derelict land. Pension funds rely on global returns. All true and yet partial. The gains are concentrated, while the risks are socialised. When property bubbles inflate, it is local people who are priced out. When utilities falter, it is customers who pay more. When political influence is purchased through donations and lobbying, it is democracy that is diluted.

Britain has not been conquered by foreign flags. It has been integrated into a global system in which capital outranks citizenship. The rich and powerful, wherever they originate, shape planning law, tax policy and regulatory frameworks to protect and extend their position. Parliament remains sovereign in theory. In practice, policy too often bends towards those who can move money at speed and scale.

The polemic, then, should not be against foreigners. It should be against a political economy that treats the country as an asset class. Sovereignty is not merely the right to pass laws. It is the capacity of a people to determine the conditions of their common life. When land, infrastructure and culture are primarily valued for their yield to distant investors, that capacity erodes.

Britain’s challenge is not to retreat into nationalism but to confront the concentration of ownership and influence that cuts across borders. Transparency, tighter regulation of political finance, limits on speculative vacancy and a reassertion of public interest in critical infrastructure are not radical fantasies. They are, at the very least, democratic necessities. For some, this is not nearly enough. Many aspire to a revolutionary change. Unfortunately, when one is trapped in a global system of capital, it takes much more than domestic radicalism to make a real difference. Too many forces are at play that seek to prevent it, often by any means possible.

The real question is simple and uncomfortable: who is Britain for? If it is primarily for those who can afford to buy it, whether they live here or not, then the drift will continue. If it is for those who live and work within it, then the structures that privilege the rich and powerful must be challenged, not merely managed. New models are required in which the ownership is transferred to us and the generations that follow us.

Until then, the skyline of empty luxury flats will stand as monuments to a deeper reality: that in modern Britain, capital has found a home, even as many citizens struggle to find one of their own. Money will continue to be drained outwards to the few while the great many continue running and jumping the hurdles created for them.