Throughout history, instances of oppression and captivity have repeatedly demonstrated a disquieting truth: the majority of people, when subjected to significant coercion or authority, often fail to fight back against their oppressors or captors. This phenomenon has intrigued and perplexed scholars across disciplines. It has prompted investigations into the psychological, sociological, and philosophical dimensions of human behaviour to better understand why people submit to authority, even when it is harmful or unjust. The following will examine key theories and empirical examples that shed light on this issue, drawing from the fields of psychology, sociology, and philosophy.

Psychological Explanations

- The Power of Learned Helplessness Learned helplessness is a psychological condition in which individuals who have been subjected to prolonged control or trauma come to believe they are powerless to change their situation, even when opportunities for escape or resistance arise. The theory was developed by psychologists Martin Seligman and Steven Maier in the 1960s through experiments on dogs. They found that when animals were exposed to inescapable shocks, they eventually stopped trying to escape, even when escape became possible later. This concept applies to humans in oppressive conditions as well, where prolonged exposure to adversity diminishes the perceived ability to fight back.

An example of learned helplessness in human captivity is the experience of domestic abuse victims. Often, individuals in abusive relationships exhibit behaviours indicating that they feel incapable of leaving, even when external help is available. They become conditioned to believe that resistance is futile, having experienced failure in previous attempts to assert control over their situation.

- The Stockholm Syndrome Phenomenon One of the most widely known psychological responses to captivity is Stockholm Syndrome. First identified after a 1973 bank robbery in Stockholm, Sweden, this phenomenon describes the emotional bond that can develop between captors and captives. Hostages may come to sympathise with their captors, even to the point of defending them or refusing to escape when given the chance. Psychologists attribute this reaction to a survival mechanism in which victims align themselves with the oppressor as a way to reduce harm.

Stockholm Syndrome highlights the paradox of emotional dependence on one’s oppressors, where hostages begin to see their captors as protectors rather than aggressors. This counterintuitive attachment can be explained through a combination of trauma bonding, fear, and the natural human desire for safety and predictability, even if it comes from a harmful source. The case of Patty Hearst, an American heiress kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army in 1974, provides a notable example. She later appeared to support her captors’ ideology and even participated in their criminal activities. Her case remains one of the most infamous examples of Stockholm Syndrome.

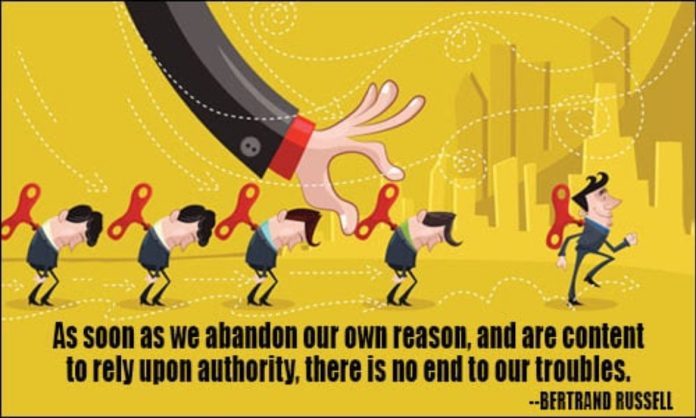

- The Role of Obedience and Authority Psychologist Stanley Milgram’s landmark obedience experiments in the 1960s provide a powerful illustration of how ordinary individuals can be compelled to comply with authority figures, even to the point of committing harmful acts. In the experiment, participants were instructed by an authority figure to administer increasingly painful electric shocks to a person in another room (who was, in reality, an actor). Despite the actors’ cries of pain, many participants continued to follow instructions.

Milgram’s findings suggest that the social structure of authority plays a significant role in determining how people behave under oppression. When faced with an authoritative figure or a structured system, people tend to conform to their roles within that system, often placing responsibility for their actions onto the authority figure. This diffusion of responsibility makes it easier for individuals to accept harmful actions, as they no longer feel personally accountable for their decisions.

Milgram’s work is further supported by real-world examples, such as the behaviour of Nazi soldiers during World War II. Many claimed that they were simply “following orders” when committing atrocities, underscoring how individuals can become agents of violence without personal moral reflection when directed by a superior power.

- The Bystander Effect Psychological studies also highlight the bystander effect as a factor in why people do not resist their oppressors or captors. The bystander effect, first examined by social psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley, posits that individuals are less likely to take action in a group setting, as they assume someone else will intervene. The diffusion of responsibility in larger groups means that individuals feel less personal obligation to act.

This phenomenon can explain why populations under oppressive regimes or groups of captives do not always fight back. In group scenarios, individuals may assume that others are better suited to lead resistance efforts, or they may simply be paralysed by the fear that acting alone will lead to harsher reprisals.

Sociological Explanations

- Social Conformity and Group Dynamics Sociologist Émile Durkheim’s work on social cohesion and collective consciousness offers insights into why people may submit to oppression. Durkheim argued that society functions on shared beliefs and norms, which individuals internalise and follow in order to maintain social order. When people are part of a group, they are strongly influenced by the expectations and behaviours of others in that group.

This sociological insight is essential for understanding why individuals under authoritarian regimes often do not resist. Social conformity pressures make individuals reluctant to challenge the prevailing system, as doing so would risk social ostracism, punishment, or worse. Durkheim’s theories are particularly relevant when examining oppressive societies, where dissent is criminalised, and conformity is equated with survival.

An example of this can be seen in totalitarian regimes such as North Korea, where an entire population has been systematically conditioned to conform to a rigid social order. Under such extreme circumstances, individuals are dissuaded from resistance not just through direct fear of punishment, but also through the collective mindset that loyalty to the state is a moral duty.

- Marxist Theory and the Role of Ideology Karl Marx’s concept of “false consciousness” offers a different perspective on why people may not resist oppression. According to Marx, the ruling class controls not only the means of production but also the ideological structures that shape people’s beliefs and values. Through institutions like the media, education, and religion, the oppressors instil a worldview that makes the existing power structures appear natural and just. This prevents the oppressed from recognising their exploitation and rising up against it.

For instance, in capitalist societies, workers may not fight back against exploitative conditions because they have internalised the idea that such conditions are part of the natural order of life, or they may believe in the possibility of personal success within the system (the “American Dream”). This kind of ideological control is subtle but deeply effective in maintaining the status quo.

An empirical example of false consciousness can be found in the class dynamics of Victorian Britain. Workers in the Industrial Revolution often endured harsh working conditions and meagre pay but did not organise against their capitalist employers on a large scale. The pervasive belief that hard work could lead to social mobility and that the system itself was inherently just played a significant role in quelling widespread resistance.

- Fear of Social and Economic Repercussions Sociologists also point out that fear of social or economic repercussions is a powerful deterrent to resistance. Oppressive systems often maintain control by threatening individuals with loss of livelihood, imprisonment, or even death. The consequences of rebellion are not merely personal but can extend to one’s family or community, creating a collective fear that paralyses action.

This dynamic is evident in many historical instances of oppression, such as apartheid in South Africa. Many black South Africans did not actively resist the regime for fear of violent reprisals, imprisonment, or economic deprivation. Similarly, during the era of McCarthyism in the United States, the fear of being labelled a communist sympathiser led many to remain silent, as speaking out could result in the loss of employment, social status, and personal freedom.

Philosophical Explanations

- Thomas Hobbes and the Desire for Security Philosophical explanations for why people do not resist their captors or oppressors often draw on the work of political theorists such as Thomas Hobbes. In his seminal work Leviathan (1651), Hobbes argues that human beings, in their natural state, are driven by fear of death and a desire for self-preservation. As a result, they willingly submit to authority in exchange for security and order. According to Hobbes, people will tolerate significant amounts of oppression as long as it ensures their survival and protects them from the chaos of anarchy.

Hobbes’ theory can explain why people under tyrannical regimes or in captivity often choose submission over resistance. The desire for security and stability may outweigh the perceived benefits of rebellion, particularly when the consequences of failure are severe. For many, the risk of violent retaliation or societal collapse is too great to justify resistance.

- Jean-Paul Sartre and the Notion of “Bad Faith” Jean-Paul Sartre, a 20th-century existentialist philosopher, introduced the concept of “bad faith” to describe the human tendency to deny one’s freedom and responsibility by conforming to societal expectations. Sartre argued that people often choose inauthenticity and self-deception because true freedom is a burden. The freedom to act also brings with it the responsibility for the consequences of one’s actions, and many people prefer to avoid this weight by submitting to external forces.

Sartre’s concept of bad faith can be applied to scenarios of oppression, where individuals may avoid the moral and practical burden of resistance by convincing themselves that they have no choice but to submit. They may believe that their situation is unchangeable or that any effort to resist would be futile or dangerous. This avoidance of authentic action serves as a coping mechanism, allowing people to live within an oppressive system without confronting the uncomfortable truth of their own freedom.

- Friedrich Nietzsche and the “Slave Morality” Friedrich Nietzsche offers another philosophical lens through his concept of “slave morality,” which he contrasts with “master morality.” According to Nietzsche, slave morality is characterised by passivity, humility, and a resentment of the powerful. This mindset arises in oppressed populations who, unable to assert their own power, develop a moral framework that justifies submission and frames it as virtuous.

Nietzsche’s ideas provide insight into why people may not fight back against oppression. Slave morality allows the oppressed to rationalise their lack of resistance by viewing it as morally superior to the violent or assertive behaviour of their oppressors. In this way, Nietzsche suggests that oppressed people may psychologically compensate for their lack of power by embracing values that encourage passivity and submission, rather than rebellion.

Empirical Examples and Historical Contexts

- Nazi Germany and the Holocaust The Holocaust is one of the most harrowing examples of large-scale oppression where many victims did not resist. While there were instances of rebellion, such as the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the majority of Jews and other targeted groups did not fight back against the Nazis. This can be attributed to a combination of factors: fear of violent reprisals, the breakdown of social structures, and the systematic dehumanisation of victims. Psychological factors, such as learned helplessness and the bystander effect, combined with the sociological weight of group conformity and fear of authority, played a significant role in the widespread submission to Nazi control.

- The African Slave Trade During the transatlantic slave trade, millions of Africans were captured, transported, and enslaved in the Americas. While there were numerous instances of resistance and rebellion, the majority of enslaved individuals endured their oppression without organised revolt. This is largely attributable to the brutal conditions of slavery, the destruction of cultural and familial ties, and the overwhelming power imbalance between the enslaved and their captors. Moreover, sociological factors such as false consciousness and the fear of brutal punishment further explain why resistance was not more widespread.

Challenging Is The Exception Not The Rule

The reluctance of most people to fight back against their oppressors or captors is a complex phenomenon with roots in psychology, sociology, and philosophy. Psychological mechanisms such as learned helplessness, Stockholm Syndrome, and obedience to authority can make resistance seem impossible or unwise. Sociological factors like social conformity, false consciousness, and fear of repercussions help maintain the structures of oppression. Finally, philosophical insights from thinkers such as Hobbes, Sartre, and Nietzsche provide further understanding of the human desire for security, the evasion of personal responsibility, and the moral frameworks that justify submission.

In combination, these theories highlight the deeply ingrained tendencies that prevent resistance, even in the face of extreme adversity. While individual and collective rebellion is possible and does occur, these barriers demonstrate why it is the exception rather than the rule.