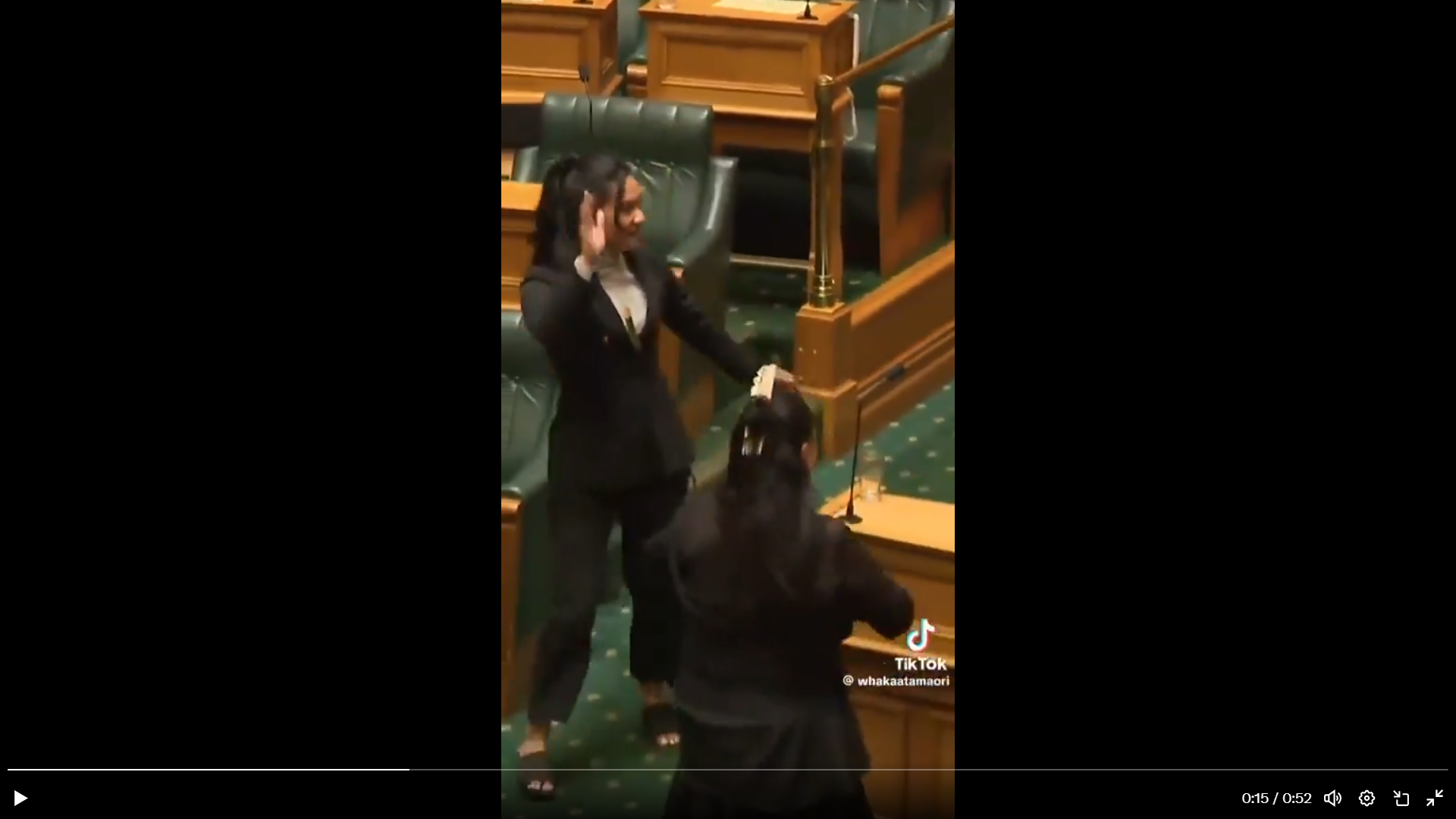

The New Zealand government is pulling back on protecting Māori rights, sparking protests from indigenous lawmakers who oppose the decision with their traditional “haka” chant.

The New Zealand government is pulling back on protecting Māori rights, sparking protests from indigenous lawmakers who oppose the decision with their traditional “haka” chant.

— Suppressed News. (@SuppressedNws) November 14, 2024

This is powerful. pic.twitter.com/ed5OKaDRB1

The Oppression of Maoris In New Zealand

The oppression of the Māori people in New Zealand is a complex and long-standing issue that spans centuries. The Māori, the indigenous Polynesian people of New Zealand, have faced considerable social, political, and economic challenges since the arrival of British settlers and the establishment of British rule. This oppression has been marked by a systematic erosion of Māori land ownership, culture, and language, as well as marginalisation within the socio-economic landscape of New Zealand. From the initial contact in the late 18th century to present-day struggles, the experience of the Māori people encapsulates both resilience and profound challenges. An understanding of the history of Māori oppression requires delving into the interactions between the Māori and European settlers, examining key legislative acts, and exploring ongoing issues faced by the Māori community.

The arrival of British settlers in the late 18th century marked the beginning of a new and increasingly oppressive period for the Māori people. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the Māori lived in tribal communities with complex socio-political structures and a well-established culture deeply connected to the land. However, the advent of European settlers brought a stark shift. Early European explorers, such as Captain James Cook, encountered the Māori in the late 1700s, and soon after, trade relationships began to form. The Māori were initially receptive to trade, exchanging resources like flax, timber, and food for European tools and goods. However, these interactions quickly began to shift the Māori way of life, introducing new technologies, diseases, and social dynamics that would ultimately undermine Māori autonomy.

A pivotal moment in the history of Māori oppression came with the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. The treaty, often viewed as New Zealand’s founding document, was an agreement between the British Crown and various Māori chiefs. The British presented the treaty as a means to protect Māori rights, guarantee ownership of land, and establish a framework for peaceful coexistence. However, the reality of the treaty and its subsequent interpretation differed significantly from its stated purpose. The treaty was drafted in both English and Māori, yet the two versions contained discrepancies that created considerable confusion and conflict. The English version promised British sovereignty over New Zealand, while the Māori version implied a more collaborative arrangement. Many Māori chiefs believed they were consenting to a partnership, not ceding full control to the British Crown. This misunderstanding became the basis for decades of land confiscation, marginalisation, and disenfranchisement of the Māori people.

The Treaty of Waitangi became a tool of colonial control rather than the protective document it was purported to be. Soon after its signing, the British Crown began to assert dominance over the Māori by acquiring large tracts of land through questionable means. Land was, and still is, of central importance to Māori culture and identity. The Māori concept of land, or “whenua,” is one of deep spiritual and familial significance, as it is considered an ancestral resource that connects past, present, and future generations. For the Māori, land was not merely a commodity but a vital aspect of community and cultural heritage. Nevertheless, the Crown viewed land as a resource to be bought, sold, and exploited. This fundamental difference in perspective laid the groundwork for systematic land confiscations and disputes that continue to this day.

One of the most significant methods of land acquisition by the British was through a policy known as “raupatu,” or confiscation. During the New Zealand Wars of the 1860s, the British military seized land from Māori tribes that were deemed “rebellious.” These wars were in large part a response to Māori resistance against increasing British encroachment and control. As punishment for defiance, entire regions were stripped of Māori ownership. Under the New Zealand Settlements Act of 1863, the government confiscated land in areas such as Taranaki, Waikato, and Bay of Plenty, claiming that Māori groups in these areas had participated in acts of rebellion. The land was subsequently redistributed to European settlers, with little to no compensation provided to the Māori people. Raupatu devastated the Māori economy, severing their connection to their land and their means of self-sufficiency.

Following the New Zealand Wars and the widespread confiscation of land, the Māori were further oppressed by the introduction of legislation that systematically disadvantaged them. The Native Land Court, established in 1865, became a powerful mechanism for transferring Māori land to European ownership. The court encouraged individual rather than communal land ownership, which directly conflicted with Māori traditions. The process was fraught with legal and financial burdens for Māori landowners, many of whom were forced to sell their land simply to cover the costs of the court proceedings. Additionally, the Crown acquired a large proportion of Māori land through “purchase agreements” that were often coercive and exploitative. By 1900, Māori land ownership had plummeted from around 66 million acres to fewer than 8 million acres, largely due to these exploitative practices.

The loss of land was not the only form of oppression faced by the Māori. Cultural suppression became another significant aspect of colonial dominance, as the British sought to assimilate the Māori people into European norms. One of the most prominent forms of cultural suppression was the prohibition of the Māori language, or “te reo Māori.” During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Māori children in New Zealand schools were often punished for speaking te reo Māori, as the education system aimed to replace it with English. This policy of “English-only” education not only discouraged the use of the Māori language but also undermined Māori identity and self-esteem. For many Māori, language is inseparable from cultural knowledge, practices, and values. The marginalisation of te reo Māori contributed to a significant decline in native speakers and left subsequent generations disconnected from their linguistic and cultural heritage.

Māori social structures, which emphasised collective welfare and communal living, were also disrupted by European individualism and capitalism. Māori traditional society was based on a complex system of kinship and community responsibilities, with land, resources, and labour shared collectively. However, European settlers imposed a capitalist economy that prioritised individual wealth and property ownership. This cultural shift placed Māori communities at a disadvantage, as they were often excluded from economic opportunities, further exacerbating socio-economic inequalities. Poverty, unemployment, and lack of access to resources became widespread among the Māori, creating cycles of disadvantage that continue to affect Māori communities.

Throughout the 20th century, Māori people continued to face systemic discrimination, particularly within the legal and judicial systems. Māori were, and still are, disproportionately represented in New Zealand’s criminal justice system, with higher rates of incarceration and harsher sentencing compared to non-Māori. This over-representation is a consequence of both historical and contemporary socio-economic inequalities that stem from colonial oppression. Studies have shown that Māori are more likely to experience police scrutiny, receive fewer legal protections, and encounter bias within the courts. These disparities reflect ongoing institutional racism that affects Māori people in virtually all sectors of society.

Despite the oppression and marginalisation they have faced, the Māori have consistently resisted and sought ways to assert their rights. The Māori King Movement, or Kīngitanga, emerged in the 1850s as an expression of Māori unity and resistance to British encroachment. This movement aimed to establish a Māori monarchy that would operate independently of the British Crown, thus protecting Māori land and authority. Though the movement faced significant challenges, it became a powerful symbol of Māori identity and resilience. Other resistance efforts included non-violent protests, legal petitions, and political advocacy.

In the 1970s, a new wave of Māori activism emerged, driven by growing awareness of the extent of land loss and cultural erosion. This period saw the rise of Māori protest movements such as Ngā Tamatoa, which advocated for Māori rights, land restitution, and the revival of te reo Māori. The Māori Land March of 1975, led by Whina Cooper, became a pivotal moment in the struggle for land rights, as thousands of Māori and non-Māori supporters marched to demand the return of ancestral lands. The momentum from this movement led to the establishment of the Waitangi Tribunal in 1975, which was created to investigate breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi and address historical grievances. While the tribunal has provided a platform for some redress, progress has been slow, and many Māori believe that justice has yet to be fully served.

Efforts to revitalise Māori language and culture have gained traction in recent decades, with te reo Māori being recognised as an official language of New Zealand in 1987. Initiatives such as Māori-language education programmes, radio stations, and television channels have contributed to a resurgence in Māori cultural identity. However, challenges remain. Although there has been a revival of te reo Māori, language fluency among younger generations is still limited, and many Māori continue to face social and economic barriers.

Today, the Māori people continue to fight for equity, representation, and respect for their rights. Despite legislative advancements and public recognition of past wrongs, the legacy of colonialism remains evident in the socio-economic disparities experienced by Māori communities. Māori are disproportionately affected by issues such as poverty, unemployment, and limited access to healthcare and education. Health statistics reveal that Māori have higher rates of chronic illness and lower life expectancy compared to non-Māori, underscoring the lasting impact of historical oppression on current generations.

The legacy of colonialism has also left an imprint on the environmental landscape. Many Māori view the protection of natural resources as integral to their cultural and spiritual identity. However, land dispossession and environmental degradation have threatened traditional Māori ways of life. Initiatives to protect Māori land and waterways, such as the campaign for the Whanganui River to be granted legal personhood, reflect the ongoing struggle to preserve Māori environmental stewardship in the face of modern economic pressures.

The oppression of the Māori people in New Zealand is not just a historical phenomenon but an ongoing issue that requires continued attention and action. Addressing the injustices of the past and supporting Māori self-determination are crucial steps toward building a more equitable society. Māori culture, language, and traditions are integral to New Zealand’s identity, yet Māori people remain disproportionately disadvantaged in numerous aspects of life. The government has made some efforts to address these issues, yet many Māori feel that these efforts fall short of genuine reconciliation and empowerment.

As New Zealand strives to reckon with its colonial history, the future of Māori rights and self-determination remains uncertain but hopeful. Recent years have seen a growing awareness among both Māori and non-Māori of the need for equity and justice. Increasingly, non-Māori New Zealanders are recognising the importance of acknowledging the Treaty of Waitangi not merely as a historical document but as a living agreement that requires active commitment. Māori leaders, activists, and communities continue to advocate for their rights, emphasising the importance of land restitution, cultural revitalisation, and social justice. The journey toward genuine reconciliation will require a shared commitment to recognising Māori rights, addressing systemic inequities, and honouring the historical and cultural significance of the Māori people in New Zealand’s past, present, and future.