The so-called racism definition controversy currently being played out in the Zionist controlled Labour Party is yet another example of truth and reality playing tenth fiddle to the Machiavellian nature of party politics. People who tick all or most of the boxes on the psychopath test often end up at the helm surrounded by people who should be in the same padded cell. While the corporate media is content to merely print the press releases and comment around the edges depending upon their bias, it is up to the independent media to create a path to the light. The following is another attempt at just that.

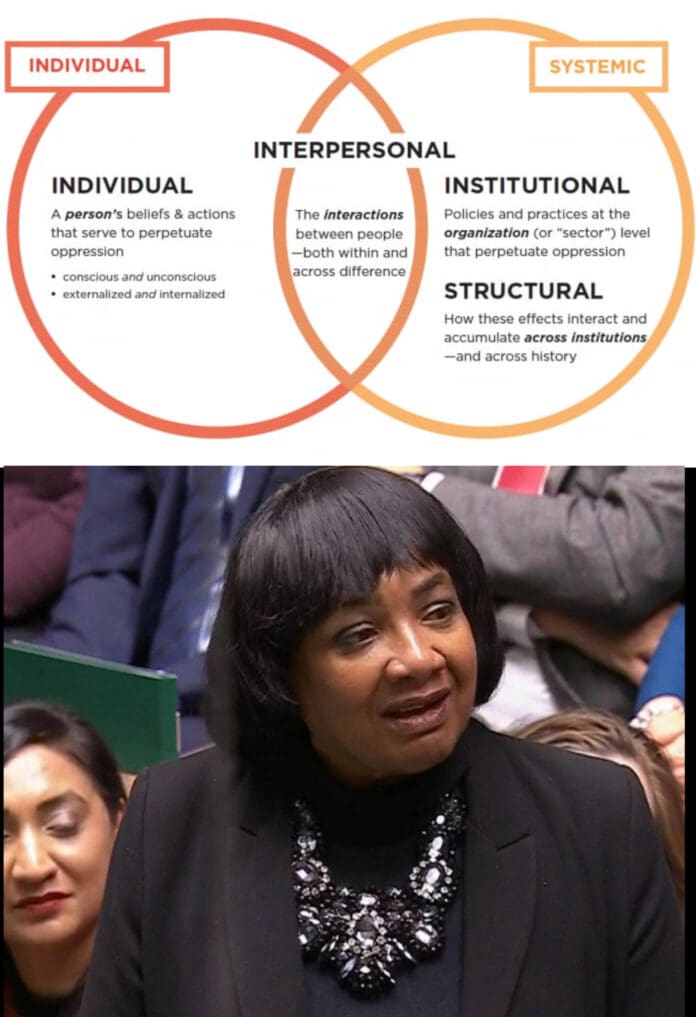

Racism is not a singular phenomenon. It is not limited to a few isolated slurs or violent incidents. Rather, it is a complex and multi-layered social system that permeates every facet of society, from our institutions and cultural norms to the ways we perceive ourselves and others. When we flatten racism into a single, catch-all category, we not only obscure its true nature, but we also hinder efforts to challenge it meaningfully.

To dismantle racism, we must understand its different forms, whether structural, institutional, cultural, interpersonal, and internalised and recognise that not all experiences of racism are identical. As Diane Abbott recently stated in a widely criticised yet sociologically valid comment:

“Clearly, there must be a difference between racism which is about colour and other types of racism because you can see a Traveller or a Jewish person walking down the street, you don’t know.

I just think that it’s silly to try and claim that racism which is about skin colour is the same as other types of racism. I don’t know why people would say that.”

Her words caused a stir, yet they highlight an essential truth: not all racisms operate in the same way and to pretend they do is to ignore crucial sociological realities.

1. Interpersonal Racism

This is the most familiar form of racism: individual acts of prejudice, hostility, or violence based on perceived race or ethnicity. Whether it’s a racial slur on public transport or a casual microaggression in the workplace, these incidents are personal and visible.

Yet even here, visibility matters. A Black person, for example, may experience immediate, spontaneous forms of racism simply due to skin colour, something that is not optional or concealable. This is what Diane Abbott refers to: the immediacy of anti-Black racism based on physical appearance.

Conversely, other groups, including Jewish people or Irish Travellers, may experience racism differently, often marked by cultural signifiers, surnames, or known identities, rather than appearance alone. This doesn’t mean their oppression is less serious, but that it operates through different social mechanisms.

2. Institutional Racism

Institutional racism involves the policies and practices embedded within institutions that systematically disadvantage racialised groups. This concept gained traction in Britain following the 1999 Macpherson Report, which investigated the Metropolitan Police’s handling of the racist murder of Stephen Lawrence. The report concluded that the force was “institutionally racist”, a term that shocked many but accurately captured how discriminatory outcomes can be produced without explicit racist intent.

Examples abound: Black Caribbean pupils are disproportionately excluded from British schools. Black patients are less likely to be offered adequate pain relief. Black drivers are far more likely to be stopped and searched by police. In each case, the individual’s race is immediately legible and often, this visibility is enough to trigger bias.

3. Structural Racism

Structural racism refers to the interconnected system of laws, policies, institutions, and ideologies that maintain racial inequality across society. These inequalities are the legacy of colonialism, slavery, empire, and decades of discriminatory social policy.

For example, Black households in the UK are significantly less likely to own property, are overrepresented in precarious employment, and experience poorer health outcomes. These patterns are not incidental. They reflect how race and class are tightly interwoven in the social fabric of Britain. Crucially, structural racism doesn’t rely on individuals being consciously racist; it persists regardless.

Sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva calls this colour-blind racism, a form of racism that persists under the guise of neutrality by pretending not to “see race” while continuing to produce deeply racialised outcomes.

4. Cultural Racism

Cultural racism involves the devaluation or stigmatisation of a group’s language, customs, religion, or worldview. It is often subtle and embedded in dominant representations, such as negative media portrayals or the exclusion of minority histories from school curricula.

Stuart Hall, a pioneer of cultural studies, argued that media narratives help “fix” racial meanings, often positioning Black people as threatening or exotic and Muslims as suspect or un-British. Cultural racism doesn’t always rely on skin colour, it targets identity, values, and symbols, but again, it operates differently depending on how visible or legible those identities are.

5. Internalised Racism

Internalised racism occurs when marginalised individuals absorb the negative stereotypes and beliefs of the dominant culture, leading to feelings of inferiority, self-doubt, or even prejudice against their own group.

Frantz Fanon, in Black Skin, White Masks, described how colonised people often come to emulate the values of the coloniser, believing whiteness represents civility, intelligence, and beauty. Internalised racism shows how deeply oppression can infiltrate the psyche.

Defending Diane Abbott’s Comment

Diane Abbott’s assertion that racism based on visible skin colour is qualitatively different from other forms reflects these layered realities. Her critics often misunderstand her point, interpreting it as a denial of anti-Semitism or anti-Traveller discrimination. In truth, she acknowledges their suffering while pointing out that the mechanisms of racism differ.

To suggest that all racisms are identical is not only sociologically inaccurate but also flattens the distinct histories, oppressions, and experiences of different groups. Anti-Black racism, for instance, is rooted in centuries of slavery, colonialism, and dehumanisation based on phenotypic difference. This kind of racism is immediate and ever-present; one cannot “hide” their Blackness.

Anti-Semitism and anti-Traveller racism are equally dangerous and often deadly, but they function through different codes, including conspiracy theories, scapegoating, or cultural vilification. Understanding these nuances helps us combat all forms of racism more effectively, rather than pitting one group’s suffering against another’s.

The Danger of Oversimplifying Racism

By treating racism as a flat category, we ignore its multiple forms and causes. We allow governments and institutions to declare themselves “not racist” simply because they do not use slurs, while continuing to uphold systems that produce racial inequality. Worse, we set oppressed groups against each other in a contest of victimhood, rather than building solidarity through shared struggle and mutual recognition.

Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality reminds us that people experience oppression in layered and specific ways. A Black woman will experience racism and sexism in ways that differ from a white woman or a Black man. A working-class Jewish person will experience anti-Semitism and classism together, not separately.

Only by embracing this complexity can we design policies, education, and resistance that are truly transformative.

In summary, racism is not one thing; it is many. It can be personal or systemic, visible or hidden, cultural or institutional. Diane Abbott’s remarks, while controversial to those who do not or choose not to understand, draw attention to a truth often ignored in public discourse: not all racisms operate the same way, and recognising this is not divisive; it is essential.

To fight racism, we must understand its full anatomy. We must listen to those who experience it differently. And above all, we must reject the shallow comfort of simplification in favour of the hard, necessary work of nuance.