The worst ever disaster in British maritime history occurred at about 3.30pm on June 17th 1940 and you have probably never ever heard of it!

If you ask the average person in the street “What was the greatest British tragedy at sea” The chances are that you will get one of three answers. RMS Titanic, RMS Luisitana or HMS Hood.

On Titanic there were 1,517 lives lost. On Luisitania there were 1,195 and on HMS Hood 1,416. A total of 4,128. But let us start at the beginning.

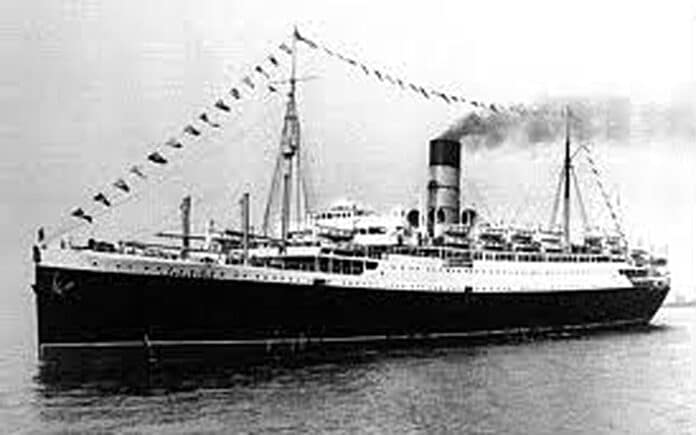

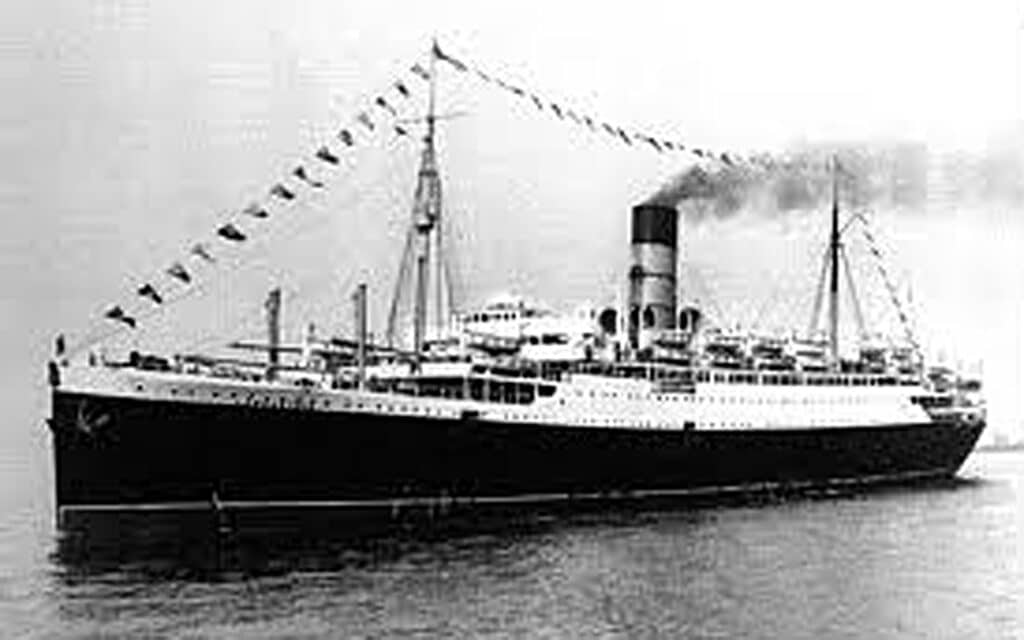

Two weeks after the evacuation of 338,226 troops and civilians from the beaches at Dunkirk, two troopships, once transatlantic liners, Oronsay and Lancastria were waiting in the Loire estuary off St Nazaire, Brittany to help evacuate the 200,000 or so troops of the British Expeditionary Force (The BEF) who were still in France.

The troops (and civilians) were ferried out to the waiting ships by small boats, tugs and a destroyer HMS Highlander as the bigger ships were unable to dock at St Nazaire.

At 1.48 in the afternoon, Ju88 dive bombers attacked the Oronsay scoring a hit on her bridge which disabled her, so all the small ships took their passengers direct to Lancastria.

The crew tried to keep a tally of how many were on board but they lost count at 5,000 and there were still more piling on board.

At about 3.30pm several Junkers Ju88s returned and this time targeted the Lancastria. She was hit by three bombs which penetrated the forward holds killing or injuring most of the occupants and blowing out hull plates on the port side causing very rapid flooding of the forward part of the ship.

Lancastria sank rapidly by the bow and within 23 minutes had rolled over onto her port side and disappeared under the waters of the Loire estuary taking with her somewhere between four thousand and seven thousand men, women and children. Yes there were children on board, the youngest survivor was 2 year old Jaqueline Taylor, who’s parents had worked for Fairy Aviation in Belgium.

The “Oh so gallant” pilots of the Ju88s from Kg30 now returned to the carnage and proceeded to machine gun the survivors and try to set fire to the oil on the water. This behaviour set the pattern of most of the nazi actions for the next four years.

One 19 year old soldier had marched, cycled, cadged lifts and walked nearly 300 miles from somewhere north ofParis carrying all his kit, rifle, ammunition, bayonet, webbing, blanket, tin helmet and greatcoat. He was terrified of losing anything in case the Quartermaster Sergeant made him pay for it!

When on board he was told that there was a bar below decks with English beer but he decided that as there were so many on board he would forgo the opportunity and stayed on deck at the stern.

When the bombs hit and the ship began to sink, he took to the water and was picked up three hours later wearing just one sock and a wristwatch!

He was lucky! Many were blown to pieces in the bombed holds, many drowned in the oily water and many were machine gunned as they clung to the upturned hull or tried to swim for their lives.

That 19 year old who had learned to swim in the reservoirs serving the mills of Manchester was my Dad and if he had not survived, I would not have been born.

And why have you never heard of this disaster? Winston Churchill in his “A History of the English Speaking People” states that he banned the reporting of the sinking because the news of other losses was so bleak that the public could not take any more but that there was so much else going on that he “forgot” to lift the restriction after a suitable time.

This injunction of silence must have filtered down the ranks because my Father told me many years after the event that he had been threatened with a Court Martial if he ever said a word about the sinking. In fact that addiction to silence still rules Whitehall because though the government was petitioned several times to have the wreck site designated an official maritime war grave, they refused.

In fact it was the Scottish Parliament who recognised the loss of life and the endurance of the survivors by issuing in 2008, a commemorative medal to the survivors of the tragedy and the next of kin of those who died.

That medal is one of my dearest posessions.

Ian Brooke.

01305 775812

07778 210848

If you would like me to give an illustrated talk about Troopship Lancastria to your group or club, please email

PLEASE SUPPORT US FOR JUST £2 A MONTH