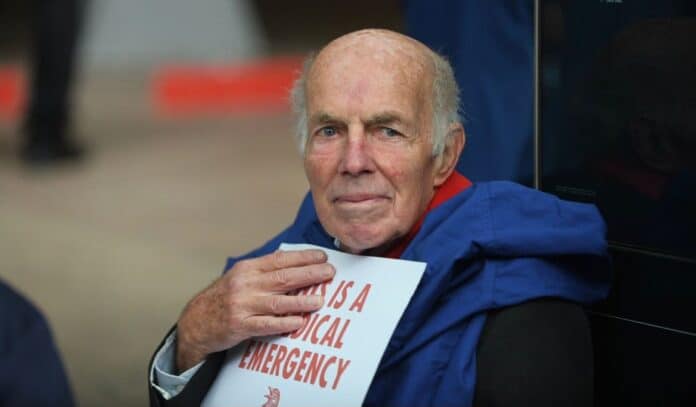

Dr. Andrew Stevenson, surgeon – qualified 21 years. “The burning of fossil fuels used to be for the advancement of human society. It is now the mechanism of its destruction. If we don’t leave oil in the ground. Our children and those forever more will have no future. Stop financing fossil fuels.”

Key facts of how climate change will impact upon health

- Climate change affects the social and environmental determinants of health – clean air, safe drinking water, sufficient food and secure shelter.

- Between 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected to cause approximately 250 000 additional deaths per year, from malnutrition, malaria, diarrhoea and heat stress.

- The direct damage costs to health (i.e. excluding costs in health-determining sectors such as agriculture and water and sanitation), is estimated to be between USD 2-4 billion/year by 2030.

- Areas with weak health infrastructure – mostly in developing countries – will be the least able to cope without assistance to prepare and respond.

- Reducing emissions of greenhouse gases through better transport, food and energy-use choices can result in improved health, particularly through reduced air pollution.

Climate change

Over the last 50 years, human activities – particularly the burning of fossil fuels – have released sufficient quantities of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases to trap additional heat in the lower atmosphere and affect the global climate.

In the last 130 years, the world has warmed by approximately 0.85oC. Each of the last 3 decades has been successively warmer than any preceding decade since 1850(1).

Sea levels are rising, glaciers are melting and precipitation patterns are changing. Extreme weather events are becoming more intense and frequent.

What is the impact of climate change on health?

Although global warming may bring some localized benefits, such as fewer winter deaths in temperate climates and increased food production in certain areas, the overall health effects of a changing climate are overwhelmingly negative. Climate change affects many of the social and environmental determinants of health – clean air, safe drinking water, sufficient food and secure shelter.

Extreme heat

Extreme high air temperatures contribute directly to deaths from cardiovascular and respiratory disease, particularly among elderly people. In the heat wave of summer 2003 in Europe for example, more than 70 000 excess deaths were recorded(2).

High temperatures also raise the levels of ozone and other pollutants in the air that exacerbate cardiovascular and respiratory disease.

Pollen and other aeroallergen levels are also higher in extreme heat. These can trigger asthma, which affects around 300 million people. Ongoing temperature increases are expected to aggravate this burden.

Natural disasters and variable rainfall patterns

Globally, the number of reported weather-related natural disasters has more than tripled since the 1960s. Every year, these disasters result in over 60 000 deaths, mainly in developing countries.

Rising sea levels and increasingly extreme weather events will destroy homes, medical facilities and other essential services. More than half of the world’s population lives within 60 km of the sea. People may be forced to move, which in turn heightens the risk of a range of health effects, from mental disorders to communicable diseases.

Increasingly variable rainfall patterns are likely to affect the supply of fresh water. A lack of safe water can compromise hygiene and increase the risk of diarrhoeal disease, which kills over 500 000 children aged under 5 years, every year. In extreme cases, water scarcity leads to drought and famine. By the late 21st century, climate change is likely to increase the frequency and intensity of drought at regional and global scale.(1)

Floods and extreme precipitation are also increasing in frequency and intensity.(1) Floods contaminate freshwater supplies, heighten the risk of water-borne diseases, and create breeding grounds for disease-carrying insects such as mosquitoes. They also cause drownings and physical injuries, damage homes and disrupt the supply of medical and health services.

Rising temperatures and variable precipitation are likely to decrease the production of staple foods in many of the poorest regions. This will increase the prevalence of malnutrition and undernutrition, which currently cause 3.1 million deaths every year.

Patterns of infection

Climatic conditions strongly affect water-borne diseases and diseases transmitted through insects, snails or other cold-blooded animals.

Changes in climate are likely to lengthen the transmission seasons of important vector-borne diseases and to alter their geographic range. For example, climate change is projected to widen significantly the area of China where the snail-borne disease schistosomiasis occurs(3).

Malaria is strongly influenced by climate. Transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes, malaria kills over 400 000 people every year – mainly children under 5 years old in certain African countries. The Aedes mosquito vector of dengue is also highly sensitive to climate conditions, and studies suggest that climate change is likely to continue to increase exposure to dengue.

Measuring the health effects

Measuring the health effects from climate change can only be very approximate. Nevertheless, a WHO assessment, taking into account only a subset of the possible health impacts, and assuming continued economic growth and health progress, concluded that climate change is expected to cause approximately 250 000 additional deaths per year between 2030 and 2050; 38 000 due to heat exposure in elderly people, 48 000 due to diarrhoea, 60 000 due to malaria, and 95 000 due to childhood undernutrition.

Who is at risk?

All populations will be affected by climate change, but some are more vulnerable than others. People living in small island developing states and other coastal regions, megacities, and mountainous and polar regions are particularly vulnerable.

Children – in particular, children living in poor countries – are among the most vulnerable to the resulting health risks and will be exposed longer to the health consequences. The health effects are also expected to be more severe for elderly people and people with infirmities or pre-existing medical conditions.

Areas with weak health infrastructure – mostly in developing countries – will be the least able to cope without assistance to prepare and respond.

WHO response

Many policies and individual choices have the potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and produce major health co-benefits. For example, cleaner energy systems, and promoting the safe use of public transportation and active movement – such as cycling or walking as alternatives to using private vehicles – could reduce carbon emissions, and cut the burden of household air pollution, which causes some 4.3 million deaths per year, and ambient air pollution, which causes about 3 million deaths every year.

In 2015, the WHO Executive Board endorsed a new work plan on climate change and health. This includes:

- Partnerships: to coordinate with partner agencies within the UN system, and ensure that health is properly represented in the climate change agenda.

- Awareness raising: to provide and disseminate information on the threats that climate change presents to human health, and opportunities to promote health while cutting carbon emissions.

- Science and evidence: to coordinate reviews of the scientific evidence on the links between climate change and health, and develop a global research agenda.

- Support for implementation of the public health response to climate change: to assist countries in building capacity to reduce health vulnerability to climate change, and promote health while reducing carbon emissions.

Ten hazards for individual health:

- Power outages in extreme weather could cripple hospitals and transportation systems when we need them most.

- Crop declines could lead to undernutrition, hunger, and higher food prices. More CO2 in the air could make staple crops like barley and soy less nutritious.

- Occupational hazards such as risk of heatstroke will rise, especially among farmers and construction workers. Labor could shift to dawn and dusk, times when more disease-carrying insects are out.

- Hotter days, more rain, and higher humidity will produce more ticks, which spread infectious diseases like Lyme disease.

- Trauma from floods, droughts, and heat waves can lead to mental health issues like anxiety, depression, and suicide.

- More heat can mean longer allergy seasons and more respiratory disease. More rain increases mold, fungi, and indoor air pollutants.

- Mosquito-borne dengue fever has increased 30-fold in the past 50 years. Three-quarters of those exposed so far live in the Asia-Pacific region.

- Senior citizens and poor children—especially those already afflicted with malaria, malnutrition, and diarrhea—tend to be most vulnerable to heat-related illnesses.

- Drought and chronic water shortages harm rural areas and 150 million city dwellers. If localities don’t adjust quickly, that number could be nearly a billion by 2050.

- Rising sea levels can threaten freshwater supplies for people living in low-lying areas. More severe storms can cause city sewage systems to overflow.

Why are the state attempting to suppress the informing of the public?

As someone who has spent over a decade studying the climate change denial movement, many of the political tactics mainstreamed by Donald Trump… and the populist right around 2015–2016 seemed familiar. Attack the experts. Launch personal attacks on opponents. Frame an email scandal to maximize political gain. Delegitimize mainstream media sources. Cast yourself as the savior of traditional American life. Climate change deniers practiced these tactics years before the Republican Party transformed from a Reagan coalition of social conservatives and small-government libertarians to a party of the populist right. While arguing against scientific consensus will always present an uphill battle, the organizers of climate change denial repeatedly prove their ability to strategically adapt to their political environment, seamlessly shifting between narratives of “climate change is not happening,” “climate change is happening but humans are not driving it,” and “climate change is happening but it is nothing to worry about.”

Considering the economic incentives of continued fossil fuel development, I expect that climate change deniers will adapt to shifting political winds for years to come and will continue to employ political tactics. In this article, I review a few facts and events to illustrate this point. For a more comprehensive overview of the players involved in obstructing action on climate change, read “From Denial to Obstruction: A Sociological View of the Effort to Obstruction Action on Climate Change” by Robert Brulle and Riley Dunlap in this issue. Ultimately, members of the climate change denial movement do not concern themselves with building fact-based objections to mainstream scientific consensus. Rather, they are focused on how to coordinate political reactions to any sort of mitigation policy effort that detracts from fossil fuel-based economic growth strategies. Thus, in my view, the tactics used to frame scientists as corrupt, activists as antiprogress, corporations as “woke,” or journalists as liars, represent a crucial element of the contemporary climate change denial movement.

The Economic Incentives of Denial

Looking at the organization of climate change denial, we quickly recognize a familiar story of corporate actors pursuing private gain, hiding information from the public, and pushing negative externalities onto society. To do this successfully, industry actors coordinate public relations campaigns and prop up their own set of experts to deny their industries have contributed to harming public health. The playbook used by climate change deniers often parallels that used by the tobacco industry to deny carcinogenic links to their product, sometimes employing the very same people who had defended Big Tobacco to protect the fossil fuel industry. Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway documented this network of iconoclastic and politically connected scientists who promote uncertainty around climate science (and other environmental and public health issues) in their book Merchants of Doubt (Bloomsbury Press, 2010).

A mixture of corporations in the fossil fuel industry (e.g., ExxonMobil), trade associations (e.g., National Association of Manufacturers), conservative philanthropists (e.g., The Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation), and conservative think tanks make up the coalition of organized climate change denial. As part of this coalition, think tanks serve a key function in using funds from corporations and philanthropists to produce the narrative work of denial in the form of research reports, newsletters, podcasts, social media posts, and op-eds. These include widely recognized names such as The Heritage Foundation, but also smaller think tanks such as The Heartland Institute that have made climate change denial their niche. Ideologically, these think tanks unite through their libertarian commitment to free markets, low taxes, and opposition to “big government,” leading various corporate funders to view them as useful vehicles for obstructing proactive climate legislation. Indeed, organizations within the climate change countermovement that have received corporate funding produce more polarizing media than those without corporate funding, and they place greater emphasis on specific themes such as the purported benefits of increased CO2 concentrations.

Various politicians representing constituents whose economic livelihoods rely on fossil fuel development and access to cheap energy also have incentives to engage in climate change denial. Treadmill of production theory in environmental sociology anticipates these types of alliances, wherein a coalition of corporations, labor, politicians, and (sometimes) consumers come together through mutual benefits realized at the cost of environmental degradation. Consistent with what my research shows, congressional representatives discuss environmental issues on their social media accounts along the political-economic lines that characterize their districts. Additionally, and unsurprisingly, legislators tend to vote against pro-environmental bills as they receive more money from industries associated with the climate change countermovement. Clearly, the alignment of near-term economic incentives with conventional fossil fuel economic development creates a receptive context for deniers’ attacks on climate science and efforts to mitigate global climate change.

The Political Culture of Denial

In my view, it is a mistake to assume that a principled commitment to libertarian principles in defense of free markets drives the climate change denial movement. Beneath the surface of the libertarian rhetoric that infused the early years of the denial discourse lay the forerunners of the modern right’s turn from libertarian-conservatism to right-wing populism. In my estimation, the mutual hatred of “the expert”—disdained as a tool of central planning in a Hayekian-inspired libertarian tradition as well as a symbol of educated elites that animates modern right-wing populism—allows these camps to find common ground in the field of climate change politics.

Years before “fake news” became a regular phrase in our political vocabulary, deniers used a variety of now-familiar tactics to shape public discourse around climate change. At the outset of my interest in studying climate change denial, I attended a well-known conference organized by The Heartland Institute in 2010, part of an annual series set up as the denial movement’s version of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Upon arrival, I entered a large conference space where hundreds of attendees gathered for dinner and to hear a keynote speaker. Having spent months consuming climate change denial content at that point, I possessed a sense of what to expect at this conference, but the scene I walked into took me aback: hundreds of animated climate change deniers excitedly shouting “Lock Him Up!” Many of the attendees were waving small hockey sticks emblazoned with “Mann-Made Global Warming,” aiming their chants at climatologist Michael Mann, author of the well-known “hockey stick” graph, and whom the denial movement accuses of manipulating data (as they do of nearly every prominent climate scientist or research group). Of course, not too many years later, rowdy crowds at Trump campaign rallies would shout “Lock Her Up!” about Hillary Clinton. This parallel illustrates a political culture undergirding the denial movement, premised not on good-faith disagreements about the proper role of government, but a visceral hatred directed at anyone identified as the enemy. In this case, enemies include most climate scientists, but also anyone perceived as an opponent to the lifestyle made possible by access to cheap fossil fuel. While I understand the motives of corporate actors as a desire to protect profits, I would characterize many of the rank-and-file activists I encountered at this conference (who were almost all white men) as motivated by threats to their “industrial” masculinity.

Another familiar parallel involves an email scandal. Perhaps no other event animated the climate change denial movement more than the infamous “Climategate” scandal. In 2009, ahead of the United Nations Copenhagen Climate Change Conference, hackers obtained emails from the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia. Among thousands of emails, climate change deniers took a small handful out of context and used them to insinuate that researchers manipulated data and misled the public about the reality of anthropogenic climate change. Sen. James M. Inhofe (R-OK), a political champion of climate change denial, pounced on the scandal to call for investigations into research sponsored by the United Nations’ IPCC. Climategate dominated U.S. news coverage of climate change for months, particularly among newspapers with conservative editorial leanings. Multiple independent investigations would later verify that no malfeasance took place and that the deniers’ narrative itself manipulated the emails, though these headlines would receive scant attention by comparison. In the end, the denial movement secured a victory: public trust in climate science eroded and belief in global warming among television meteorologists declined as a result of Climategate.

Responding to Climate Change Denial

Since the manufactured Climategate controversy, which I consider the zenith of deniers’ influence over public opinion (though their policy influence would later peak under the Trump administration), parts of the denial coalition began to suffer setbacks. As their attack tactics became progressively more hostile, climate change deniers began to lose support among corporate boardrooms. One significant moment came in 2012, when The Heartland Institute put up a billboard in Chicago equating global warming activists to the terrorist “Unabomber” Ted Kaczynski. Months earlier, a climate scientist and activist leaked several internal documents that publicly exposed the funders of The Heartland Institute’s attacks on climate science. With pressure mounting from activists, corporations such as State Farm Insurance and General Motors cut ties with the small but influential think tank. Many other corporations would end up deciding they could no longer publicly associate with climate change denial (another familiar parallel with our current political moment).

Scientists have spent years fact-checking misinformation and sometimes debating contrarian pundits. While the pursuit of “inoculating” the public from misinformation may necessitate such activities, fact-checking and communicating the scientific consensus regarding climate change insufficiently counters the power of misinformation campaigns, partly because climate change denial belongs to the same polarizing trends that establish “post-truth” discursive spaces. Despite inventive suggestions for how to leverage information technology in the battle against climate misinformation, and thoughtful strategies outlined by sociologists, the COVID-19 pandemic makes clear how readily huge swaths of our population will dismiss fact-checked statements or research coming from mistrusted sources. We currently see the resistance from millions of people to taking vaccinations prescribed by public health experts. While we can argue that the denial position creeps further to the fringe of mainstream culture as it increasingly associates with anti-science attitudes, it maintains a steady home among a sizeable and committed minority.

Despite its setbacks, the denial movement does not lack teeth or influence. Prominent figures in this realm still have opportunity to exert power through their solid standing within the Republican Party. Myron Ebell of the libertarian Competitive Enterprise Institute, for example, shaped President Trump’s Environmental Protection Agency, an administration that withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Agreement and consistently empowered industry at the cost of environmental protection. While I did not describe a comprehensive list of the political fights engaged by climate change deniers in the U.S., these accounts illustrate how the movement itself foreshadowed the entering of fringe political elements into the conservative mainstream. Financially, a coalition incentivized by fossil fuel extraction supports the climate change denial movement. Culturally, a type of identity politics embedded within carbon-intensive lifestyles animates it. Understanding these aspects provides insight into the social forces blocking action on climate change, as well as their robust power going forward.

Jeremiah Bohr, Assistant Professor of Sociology, University of Wisconsin Oshkosh

Sources:

PLEASE SUPPORT US FOR JUST £2 A MONTH