The Fool’s Flag

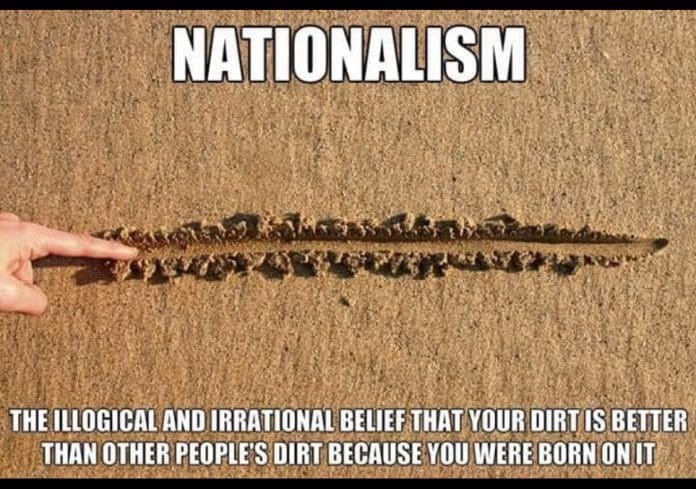

Nationalism is a strange beast, part tribal instinct, part historical accident, and almost entirely immune to reason. In recent years, with populism on the rise, flag-waving fervour has reasserted itself across the globe. From red baseball caps in America to tea-towel patriotism in post-Brexit Britain, many seem determined to define themselves by their borders, as if those lines on a map carried innate moral value.

Few public figures are better at exposing the absurdity of this mindset than American stand-up comedian Doug Stanhope. Known for his abrasive delivery and acerbic social critique, Stanhope does not just poke fun at nationalism; he tears it apart, piece by piece.

“You’re Just Lucky You Were Born Here”

In one of his best-known routines, Stanhope launches into the heart of nationalist hypocrisy with surgical precision:

“You’re not proud to be an American. You’re just proud to have lucked out and happened to be born here.”

The implication is cutting. Pride, he argues, should be the product of one’s own achievements, things we have worked for, built, or suffered through, not the arbitrary circumstances of birth. Nobody chooses their birthplace. It is assigned like a random player class in a video game. Celebrating it as if you earned it, according to Stanhope, is fundamentally irrational.

This concept, that nationalism is a default setting mistaken for identity, lies at the heart of his critique. While his language is deliberately provocative, the argument itself is deeply philosophical. What do you actually do to be proud of your nationality? Is your flag a symbol of values and culture, or just an inherited costume?

False Pride and Historical Borrowing

Stanhope does not stop at pride of place. He ridicules the strange human tendency to appropriate historical accomplishments as if they were personal achievements:

“You didn’t build the pyramids. You didn’t invent democracy. You sat on your arse and played Xbox all day. Stop acting like your passport is a personality.”

This is where Stanhope’s routine turns from simple satire to an indictment of the hollow psychology underpinning nationalist sentiment. People lay claim to their ancestors’ triumphs, or worse, their conquests, without engaging in any of the struggle or sacrifice those feats entailed. It is a parasitic kind of pride, built on a foundation of borrowed glory.

Here, Stanhope echoes the tradition of comedians like George Carlin or Bill Hicks, who did not just aim to entertain but to provoke critical thought. Nationalism, he suggests, is often little more than a lazy substitute for actual self-worth.

The British Context: Flags in the Fog

Though Stanhope is American, his skewering of nationalism travels exceptionally well, particularly to a Britain still licking its Brexit wounds. National pride has always played an ambivalent role in British culture, equal parts warm nostalgia and blustering defensiveness. Since the 2016 referendum, however, symbols of Britishness, such as the Union Jack, Churchill iconography, and even the Queen’s corgis, have been reappropriated by a vocal segment of society as shorthand for cultural identity under siege.

Meanwhile, critics of this trend are dismissed as unpatriotic or un-British, proving that Stanhope’s point is universal. Nationalism has become less about shared values and more about exclusion, a badge worn to differentiate rather than to unite.

When Stanhope says:

“I’ve never understood national pride. I don’t get it. Why would I care what a group of strangers did hundreds of years ago, before indoor plumbing, just because they happened to live on the same patch of land I was born on?”

He might just as well be addressing segments of British society who measure pride in Magna Carta quotations and wartime slogans rather than acts of modern solidarity or global cooperation.

Nationalism as Identity Crisis

What Stanhope is really exposing is a kind of identity crisis. People who feel rootless or powerless often reach for meaning in the most accessible, and often least examined, idea available to them. Nationalism fills that gap. It offers community without connection, superiority without merit, and heritage without introspection.

This is what makes it so dangerous and also so laughable. In Stanhope’s hands, nationalism is not just flawed; it is pathetic. A child playing dress-up in an ancestor’s war medals, a drunk in a pub mistaking a football chant for a political ideology.

His comedy works not because it dismisses belonging, but because it demands that we earn it through action and reflection, not birthright.

The Punchline as Antidote

The true genius of Stanhope’s bit is not just the punchlines but what they challenge us to confront. Our laziness in accepting ideas as sacred simply because they are old or because they come wrapped in bunting.

In a world where flags are draped over everything from political manifestos to social media avatars, Stanhope’s refusal to take it all seriously is a necessary cultural correction.

Ultimately, nationalism falls apart under scrutiny, and few tools are as effective at dismantling dogma as laughter. Especially when it is the kind that makes people uncomfortable for all the right reasons.

Laugh Loud, Think Hard

Doug Stanhope does not ask his audience to hate their country. He simply asks them to stop treating it like a personality trait. He invites us to laugh, not out of nihilism, but out of resistance to nonsense. And in a world overflowing with chest-thumping tribalism, that is no small service.

Sometimes, the only appropriate response to irrational pride is to shine a light on its ridiculousness and remind people that real identity is built, not inherited.