The UK has just emerged from its hottest summer since records began in 1884, with experts from the Met Office stating that human-induced climate change made this extreme heat 70 times more likely.

The new provisional data confirms that the average temperature from 1 June to 31 August 2025 reached 16.10°C across the UK, significantly surpassing the previous record of 15.76°C set in 2018. While the difference may sound small, as an average taken over three months and including both day and night temperatures, this margin is considered substantial by meteorologists.

This year’s relentless heat has knocked the famously scorching summer of 1976 into sixth place, with all of the UK’s top five warmest summers now having occurred since the year 2000—a trend the Met Office calls a “clear sign of the UK’s changing and warming climate.”

From Hosepipe Bans to ‘False Autumn’: The Impacts of the Heat

The persistent warmth wasn’t just a statistic; it had tangible consequences. The dry conditions led to hosepipe bans and “nationally significant” water shortfalls in some areas. Perhaps the most visible sign was the emergence of a so-called “false autumn.”

In August, many noticed blackberries ripening unusually early and leaves turning brown and falling to the ground. This isn’t the early arrival of the next season but a survival mechanism. Trees and plants, stressed by the extreme summer conditions, shed leaves and fruit ahead of schedule to conserve precious water and energy. This is especially crucial for younger trees with shallow roots that can’t access deeper moisture.

Kevin Martin from Kew Gardens described these false autumns as a “visible warning sign,” noting that while “trees are remarkably resilient, they are also long-lived organisms facing rapid environmental changes.”

1976 vs. 2025: Consistent Warmth vs. Intense Heatwaves

For many, the summer of 1976 remains the benchmark for UK heatwaves, remembered for a blistering 16-day spell where temperatures soared above 32°C. So how does 2025 compare?

This summer saw only nine days above 32°C. However, its record-breaking nature was due to its consistent and persistent warmth. Dr. Mark McCarthy from the Met Office explained that this demonstrates how “what would have been seen as extremes in the past are becoming more common in our changing climate.” It wasn’t about a single, dramatic heatwave, but months of unrelenting above-average temperatures.

Why Was It So Warm? A Perfect Storm of Factors

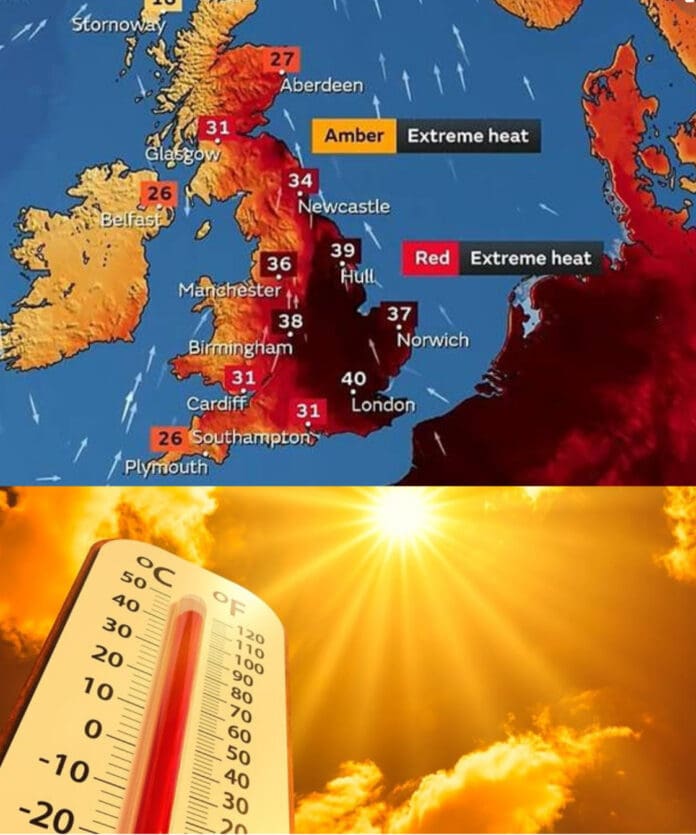

A combination of factors conspired to make this summer so exceptionally warm:

- Lingering High Pressure: Persistent high-pressure systems settled over the UK, leading to extended periods of settled, sunny, and warm weather and fuelling four distinct heatwaves.

- Exceptionally Dry Ground: The summer saw about a quarter less rain than average, following the driest spring in England for over a century. Dry ground holds less moisture, meaning less evaporation—a process that normally has a cooling effect.

- Marine Heatwave: Sea surface temperatures around the UK were also well above average. This marine heatwave had a direct knock-on effect, warming the air that passed over it.

- High Overnight Temperatures: Nights offered little respite, with high minimum temperatures helping to keep the three-month average so high.

The Overwhelming Influence of Climate Change

While natural weather patterns played a role, the Met Office’s analysis points to the overwhelming influence of climate change acting as an underlying driver. It adds a constant layer of extra heat on top of those natural patterns.

The UK is now warming by roughly 0.25°C per decade and is already at least 1.24°C warmer than the 1961-1990 average. The statistics are stark: without human-induced climate change, a summer as hot as 2025 would have been expected only once every 340 years. In our current climate, it is now expected once every five years.

This record-breaking season serves as a potent reminder that the projections of a warming world are now being felt not as a distant future threat, but as a present-day reality in the British Isles.