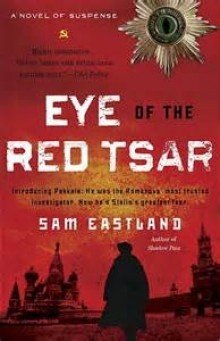

‘He was condemned to the gulag, now Stalin needs him back.’

This strap line from the front cover of this book should have been a warning of how dire the experience of reading this was going to be.

Essentially this story revolves around a former Tsarist agent Pekkala, once so close to the Romanovs and the only man Nicholas II could really trust, and the murder of the Romanovs in Ekatierinburg in 1917.

Captured and tortured by the Bolsheviks and unable to tell them the whereabouts of the Romanov fortune he is sent to a Siberian gulag and left to rot. However, our hero, known by his super scary spy name ‘The Emerald Eye’ is made of sterner stuff and manages to survive his torture and captivity.

Found, 13 years later, by a young political commissar Kirov, ‘the Emerald Eye’ is summoned from the gulag with the offer of total freedom if he cooperates in the investigation of the murder of the royal family, an investigation ordered by Stalin himself. A Stalin that Pekkala was tortured and interrogated by on his original capture.

Added to this mix is Pekkala’s brother Anton, a former Cheka agent who had been a guard on the house where the Romanovs were executed and who, surprise, surprise, has unresolved family issues with Pekkala.

Without having a thesaurus to hand it is hard for me to come up with all the synonyms that exist for the adjective ‘contrived’ but however many that exist can be applied to this poorly written and predictable story.

Told in the present and in flashback in alternate chapters a change in graphology is used to present the action occurring from the past. Presumably this change being just one of many literary devices employed to further insult the intelligence of the reader just in case the change to the past tense isn’t enough to show us where we are.

Pekkala seems to make a marvellous physical and psychological recovery from the horrors endured in his incarceration with a shave being the only therapy he requires to shake off the years of isolation, 40 degree summers, minus 40 degree winters, inadequate food, no dentistry or medical help and hard physical labour.

Eastland does allude to the psychological adjustment of a return from the gulag when Pekkalla eats a proper meal for the first time (Kirov turns out to be a former trainee chef) and when a nun grasps his hand which is his first female contact in 13 years. Unfortunately, Eastland skips over this in order to carry on with the pace of this mass of coincidences and cliché.

A love interest is of course present in this story, Ilya, a former teacher in the Romanov court whom we meet in the italicised flashback chapters, a women from the early 1900s but who seems to have seen the film ‘Show Me The Money’ as she manages to paraphrase Rene Zeilwegger’s famous line from that movie. Pekkala, with the intention of proposing to her, rows Ilya blindfolded to an island in the middle of a Petrograd Lake where he has set up an elaborate and romantic meal, on revealing to Ilya what he has done she utters the rather anachronistic phrase ‘you had me at the creaking of the oars.’

I will leave this review with a short paragraph from the book that actually made me burst out laughing whilst sitting on a bus, an example of prose so bad that the comedian Stuart Lee would have the same field day with it as he had when he deconstructed the paucity of quality of Dan Brown’s prose in his (Lee’s) stand-up act. This extract speaks far more eloquently than I in terms of how bad Eye Of The Tsar really is.

‘The child waved back, then giggled and ran behind the house. In that moment some half-formed menace spread like wings behind his eyes, as if that child was not really a child. As if something were trying to warn him in a language empty of words.’

This review first appeared in The Claudian Review

https://baggingbookers.blogspot.co.uk/2010/08/eye-of-red-tsar-by-sam-eastland.html