Once upon a time, I was ‘volunteered’ to tell a freelance trainer his contract would not be renewed. My boss’s attempt to inject a note of humour was well up to his usual standard: ‘Get rid of him, he’s as cognitively disadvantaged as a hatter.’

Call me old fashioned, but I didn’t relish the prospect of doing a fellow worker out of an income stream. On the other hand, a bit of digging revealed the freelancer in question had (a) recklessly urged people to ‘become creative’ in ways that might get them sacked; and (b) advertised himself online as a specialist in ‘workforce re-engineering’.

That took the edge off the situation; it’s hard to empathise with folk who profit from job cuts, and it’s impossible to shed a tear for anyone who hides their moral bankruptcy beneath the linguistic equivalent of a crinoline toilet roll cover.

So, grimly resigned to a spot of contractual termination with extreme prejudice, I became a middle-management Captain Willard, sailing upriver to an encounter with the business bullshit version of Colonel Kurtz. Apocalypse not now, but after tea break.

It didn’t go well. His initial tactic was to weaponise my (presumed) fear of being labelled cautious and uncreative. ‘You lack the imagination of your brave and quirky predecessor,’ he told me. ‘You’re a boring guy,’

This reminded me of a Premier League prima donna attempting to reverse a sending-off by gurning into the referee’s face, eyeballs bulging and neck veins throbbing. And was just as effective in achieving its desired aim.

Realising his red card wasn’t being downgraded to yellow, the freelancer adopted a new gambit. “You realise,” he said, “the work I’ve done with your team has placed them in a fragile psychological state? Well, if my contract isn’t renewed, I’ll be unable to bring them back to safety. Psychologically speaking.”

This heady brew of histrionic blackmail and business-centred psychobollocks was, of course, exactly as effective as the footballer gambit.

It’s easy to sneer at ethically deficient and floundering hucksters; in fact, we should do it more often. But let’s be honest: when human beings paint themselves into a corner, panic sets in and – all too often – we succumb to the urge to blurt out barely coherent and easily refuted claims and self-justifications.

Which brings me to the UK and US elections of 2024.

In January, when General Sir Patrick Sanders called for the training of a ‘citizen army’ – a ‘whole-of-nation’ approach to putting Britian on a war footing – the Tory Government declared his scenario to be unhelpful and, sensibly, ruled out any move towards a conscription model for the Army. Then, on 26 June, Rishi Sunak, our hapless and increasingly beleaguered Prime Minister, pledged to bring back compulsory national service should his party achieve a majority on 4 July.

Other brands of political desperation are available. On Friday 24 May, Sir Keir Starmer claimed an investigation into the conduct of veteran socialist MP Diane Abbott was not yet resolved. Four days later, BBC Newsnight revealed the Labour Party’s enquiries had been concluded in December 2023. Cruel treatment of Britain’s first black female lawmaker by a party hellbent on convincing corporate power that it is no longer a party of the left.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic on 30 May, a desperate politician was convicted of 34 counts of falsifying business records. He duly declared himself to be ‘a very innocent man’, indicated his intention to save the US from itself and treated the world’s media to a masterclass in venomous, stream of consciousness scapegoating: ‘Millions and millions of people pouring into our country right now from prisons, and from mental institutions, terrorists, and they’re taking over our country.’

The political narratives of the twenty-first century exhibit a startling contempt for us, their target audience. On the surface, their clunky pretexts and embarrassing inconsistencies are risible – a source of amusement – but their transparency doesn’t make them any less dangerous. When panic gets the political class in a chokehold, reality absconds from public discourse. This diminishes our ability to make informed electoral choices and shatters our trust in political processes and institutions.

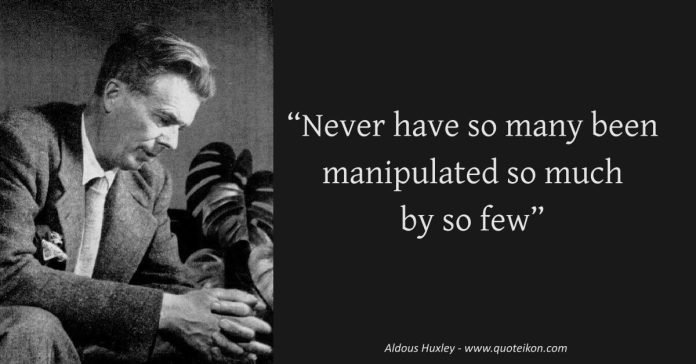

The good news was proclaimed by Aldous Huxley in 1927: ‘Facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored,’ he wrote. The bad news is that being distracted from the facts by the frantic blathering of vote-seeking politicians may destroy our fragile democracy. It will certainly condemn us to decades of powerlessness.

KEEP US ALIVE and join us in helping to bring reality and decency back by SUBSCRIBING to our Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQ1Ll1ylCg8U19AhNl-NoTg AND SUPPORTING US where you can: Award Winning Independent Citizen Media Needs Your Help. PLEASE SUPPORT US FOR JUST £2 A MONTH https://dorseteye.com/donate/