For those upset by the inset image:

Nigel Farage likes to cultivate the image of the straight-talking outsider, a man who says what others won’t and rails against a political class he portrays as lazy, corrupt and out of touch. Yet the parliamentary standards ruling into his own conduct exposes something rather more familiar: an MP who cannot follow basic rules, refuses to take responsibility when caught out, and appears far more committed to his lucrative side hustles than to the job voters elected him to do.

The parliamentary commissioner for standards has ruled that Farage breached MPs’ rules no fewer than 17 times by failing to register financial interests worth £384,000 within the required 28-day deadline. These were not trivial oversights. The undeclared payments included money from GB News, Google, X (formerly Twitter), Cameo and a six-figure-adjacent £91,200 from gold dealer Direct Bullion, for whom Farage works as a brand ambassador. Some declarations were up to 120 days late.

Although the commissioner, Daniel Greenberg, ultimately concluded that the breaches were “inadvertent” and chose not to recommend sanctions, he was clear that the decision was “finely balanced”, particularly given the high value of the interests involved. In other words, Farage came close to being formally disciplined — and only narrowly avoided it.

Farage’s response to the findings tells its own story. He apologised, said there was “no malicious intent”, and promised to do better in future. But rather than accept personal responsibility, he reached instinctively for excuses. He blamed a “very senior member of staff”. He described the failures as a “gross administrative error”. He claimed to have been “shocked” by what had happened.

Most strikingly, he suggested the problem lay not with him but with his own supposed helplessness. “You may say, why don’t I enter those things myself,” he told the commissioner. “Well I don’t do computers… so I rely on other people to do those things for me.” He even presented his lack of digital literacy as a kind of eccentric badge of honour, describing himself as an “oddball”.

This is a remarkable admission from a man paid to legislate in a modern democracy. MPs are responsible for their own compliance with the rules. Registering financial interests is not optional, nor is it some obscure bureaucratic hoop. It exists to ensure transparency and to allow the public to judge whether an MP’s outside earnings might influence their actions. Claiming not to “do computers” is not an explanation; it is an abdication.

Farage also leaned heavily on the idea that he is simply too busy to cope. His “political life”, he said, has “exploded” over the past 18 months. He is “overwhelmed in every sense”. He receives 1,000 emails a day. Reform UK, he claimed, has suffered “severe growing pains”.

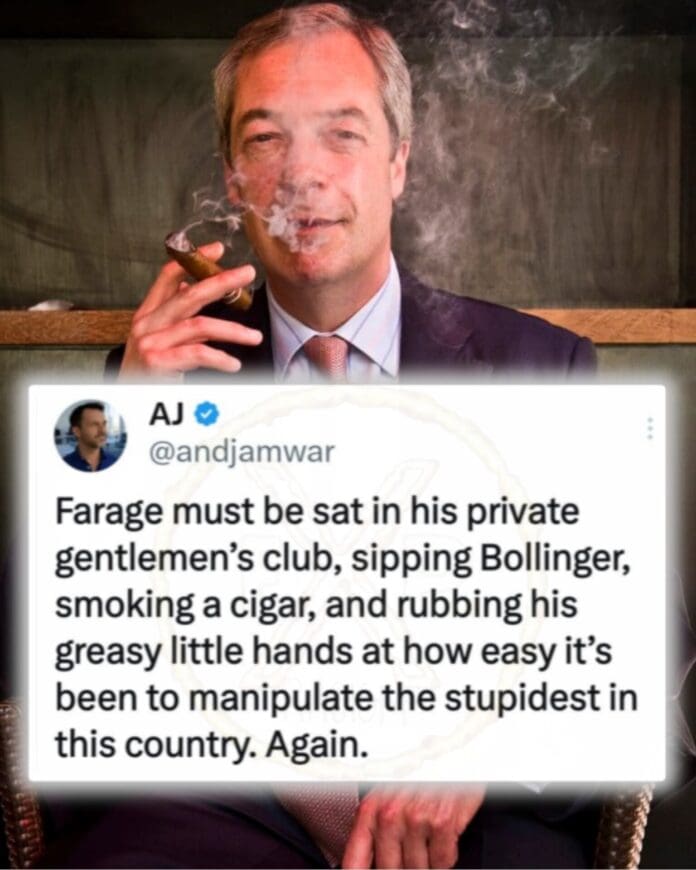

Yet this raises an obvious question: overwhelmed by what, exactly? Farage is not overwhelmed by constituency casework, legislative scrutiny or long hours in Westminster committees. He is overwhelmed because he has chosen to stack role upon role, income stream upon income stream. Broadcasting, social media platforms, brand ambassadorships, paid video messages, overseas trips — all pursued while sitting as an MP.

Farage himself all but admits this. He complained that the system for registering interests is “not designed for anybody in business”, before adding that he is not making money “as a result of being an MP” but “because I’m Nigel Farage and I’ve got other interests”. That may be true, but it entirely misses the point. The rules exist precisely because MPs have other interests. If those interests are so extensive that an MP cannot keep up with basic disclosure requirements, the problem is not the system — it is the priorities.

He even framed his outside income as a public service, noting that it allows him to claim “zero personal expenses”. This is a curious defence. MPs are not judged on whether they cost the taxpayer less than their colleagues, but on whether they do the job properly, transparently and in the public interest.

Critics have been swift to point this out. Labour accused Farage of lining his pockets instead of standing up for his constituents. The Liberal Democrats dubbed him “Five Jobs Farage”, pointing to the time he spends jetting off to the US and cashing in from his GB News show. These are barbed lines, but they land because they reflect a growing perception: that being an MP is just one gig among many for Farage, and not necessarily the most important one.

There is a deeper irony here. Farage has built his political brand on attacking elites who he claims play by different rules. Yet when he breaks the rules himself, his response is to plead inadvertence, blame staff, complain about systems, and ask for understanding because he is too busy making money elsewhere. Many MPs manage to declare their interests on time, despite heavy workloads, without claiming to be uniquely overwhelmed.

The commissioner may have closed the case, but the political verdict is harder to escape. This episode paints a picture of a man who wants the authority and platform of Parliament without the discipline and accountability that come with it. Farage can apologise as many times as he likes, but until he shows that being an MP comes before being a brand, his claims to speak for “ordinary people” will ring increasingly hollow.