Tommy Robinson is due to be released from prison earlier than expected, following a High Court decision to reduce his 18-month sentence for contempt of court. Jailed in October 2024 for breaching an injunction related to false allegations against a Syrian schoolboy, Robinson has reportedly shown a willingness to comply with the court order, despite what the judge described as an “absence of contrition or remorse.”

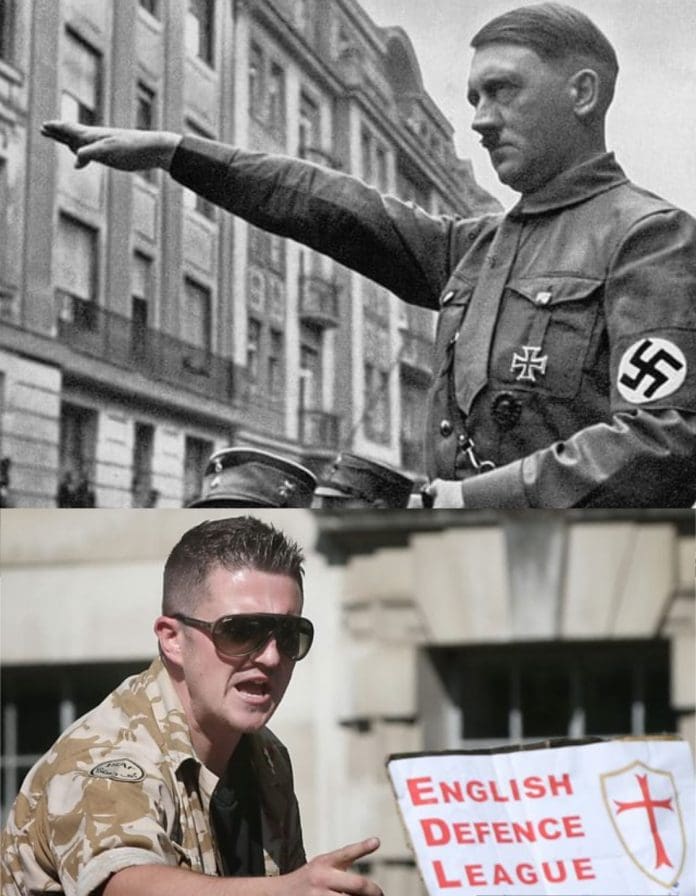

While many may view this as a footnote in Robinson’s turbulent legal record, it raises more serious questions—questions not just about the man himself, but about the political atmosphere in which he continues to operate. For historians and those concerned with the patterns of extremist politics, the comparison that surfaces time and again is Adolf Hitler.

The intent here is not to sensationalise, nor to equate Robinson with one of history’s greatest criminals in terms of scale or outcome. But the structural similarities, the mechanisms of influence, imprisonment as myth-making, scapegoating, and the consolidation of loyal networks, are too significant to ignore.

The uses of imprisonment

In 1924, Hitler was sentenced to five years in prison for his role in the Beer Hall Putsch, a failed coup attempt in Munich. He served only nine months in relative comfort. That time was not wasted. He used it to articulate his ideology in Mein Kampf and to reposition himself not as a defeated rebel but as a visionary persecuted by a corrupt system. The episode marked a turning point in how he would approach power: not through force, but through manipulation of legal and democratic institutions.

Robinson, though operating in a very different context, has also used imprisonment to his advantage. He has framed his time in jail—whether for contempt, fraud, or immigration violations—not as punishment, but as proof of establishment oppression. The narrative is familiar: he is portrayed as a man silenced for telling hard truths, a patriot jailed for challenging taboo.

This transformation of prison into a badge of honour has become a tool for public mobilisation. As with Hitler, Robinson’s supporters often cite his imprisonment not as a warning, but as validation of their worldview.

A familiar populist strategy

Both men built movements on the idea of national betrayal. Hitler drew strength from the perceived humiliation of post-WWI Germany—blaming Jews, socialists, and foreign powers for the country’s decline. He promised a return to greatness through racial and cultural “cleansing.” Robinson similarly claims that Britain is being eroded from within, often targeting Muslim communities as the source of crime, terrorism, and cultural decay.

Their rhetoric shares an emphasis on victimhood and urgency. Each casts themselves as the only figure brave enough to speak out against what they claim are existential threats. While Hitler spoke of “degeneracy” and “Jewish conspiracies,” Robinson has framed entire religious communities as inherently violent or predatory—particularly in the wake of high-profile grooming gang cases.

Such rhetoric is not only dangerous in its generalisations; it also feeds a populist logic where complex issues are reduced to simple binaries: native vs. foreign, patriot vs. traitor, and truth vs. cover-up.

Loyalty and media manipulation

In both cases, the leader’s message is reinforced by carefully cultivated inner circles. Hitler’s rise was enabled by loyalists such as Joseph Goebbels, Rudolf Hess, and Heinrich Himmler—ideologues and tacticians who helped build the Nazi Party’s infrastructure and propaganda machine.

Robinson has likewise surrounded himself with a network of far-right commentators, digital influencers, and political allies. From his ties to Canada’s Rebel Media to public endorsements by figures like Steve Bannon and Katie Hopkins, Robinson has managed to project his message far beyond traditional media. Even when deplatformed, his content continues to circulate through encrypted apps, direct messaging networks, and sympathetic fringe outlets.

This infrastructure allows him to maintain relevance even when facing legal or financial pressure. His supporters are not merely passive readers—they are part of a digital ecosystem designed to reinforce grievance, suspicion, and hostility toward mainstream institutions.

The politics of resentment

The people drawn to figures like Hitler in the 1920s and Robinson today share a sense of displacement. In post-WWI Germany, Hitler appealed to small business owners, veterans, and the lower middle classes—groups who felt abandoned by political elites and threatened by economic modernisation.

Robinson appeals to similar anxieties in post-industrial Britain. His base tends to come from areas hardest hit by economic decline, where immigration and cultural change are most visible, and where trust in the political class is weakest. His narratives offer clarity in a complex world: blame is assigned, threats are named, and solutions are framed as common sense that only the establishment dares to deny.

The success of such narratives does not depend on accuracy. It depends on resonance—and Robinson’s ability to resonate with a certain demographic remains potent.

Historical patterns—and present-day choices

It is crucial not to sensationalise. Hitler operated in a collapsed democracy and led a genocidal regime; Robinson is a fringe figure in a functioning unwritten constitutional system. But historical comparisons are not about forecasting repetition—they are about recognising patterns before they harden into something irreversible.

The early release of Tommy Robinson is not a dramatic turning point in itself. But it is a reminder of how the structures of democratic society can be exploited by those who show it little respect. It is a reminder that populist extremism does not vanish with a prison sentence. It evolves.

And it is a reminder, too, that history is not confined to textbooks. Its echoes are often clearest in the moments we dismiss as routine.