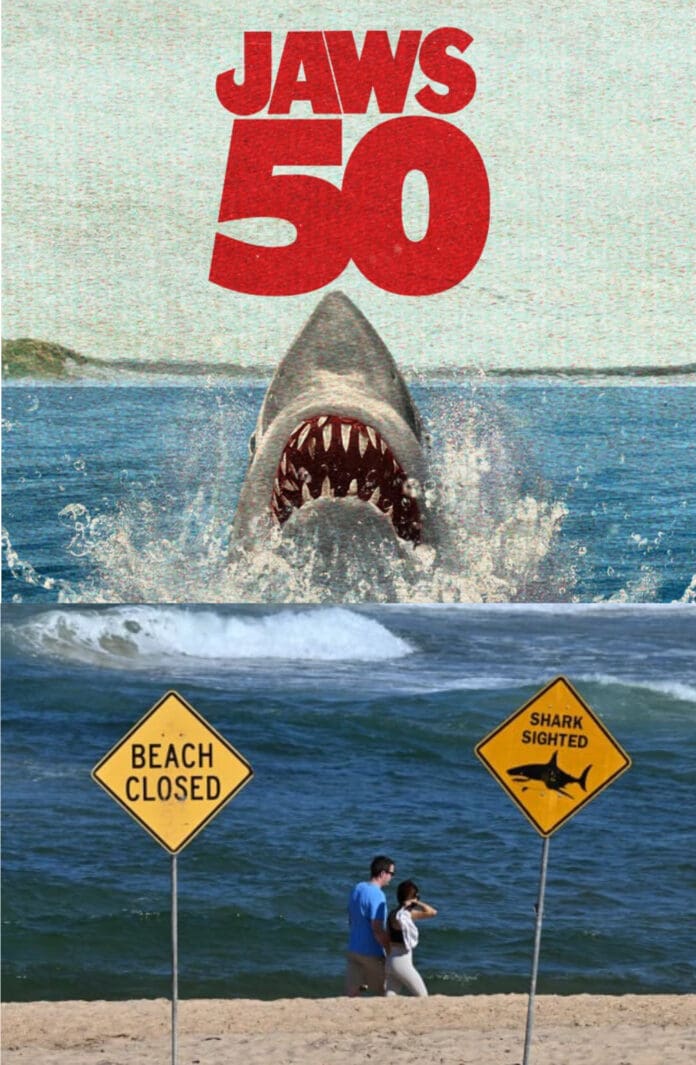

The desperate screams that pierced the air at Long Reef Beach on Saturday morning were a horrific echo of cinematic history. As witnesses described a man crying out, “I don’t want to get bitten; don’t bite me!” before a fatal shark attack, the parallels to a 50-year-old film were as unmistakable as they were tragic. This real-life drama unfolded almost exactly five decades after Steven Spielberg’s Jaws first terrified audiences, forever grafting the image of the great white shark as a vengeful man-eater onto the public psyche.

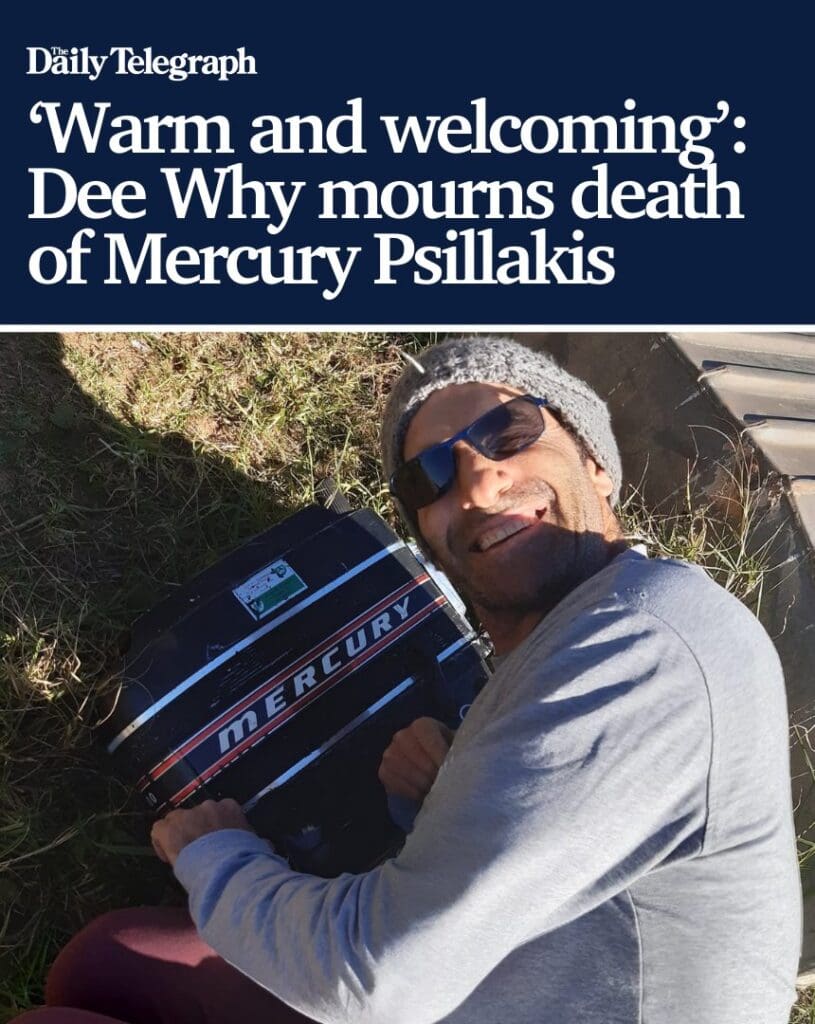

The victim, a 57-year-old experienced surfer widely named in Australian media as Mercury Psillakis, was out with friends when the attack occurred.

The scene that followed was one of chaos and bravery. His companions made it safely to shore, but shortly after, his body was found floating in the surf and recovered by other beachgoers. New South Wales Police Superintendent John Duncan confirmed the surfer suffered catastrophic injuries, losing a number of limbs in the encounter.

Witness Mark Morgenthal’s account to Sky News Australia was chillingly vivid, describing a creature of immense size. “I saw the dorsal fin of the shark come up, and it was huge… the distance between the dorsal fin and the tail fin looked to be about four metres, so it actually looked like a six-metre shark,” he said. Such dimensions, if accurate, bring to mind the fictional behemoth from Amity Island.

The Jaws Legacy: Fiction vs. Reality

The release of Jaws in 1975 was a cultural watershed. It invented the summer blockbuster and launched a genre. Yet, its most enduring and damaging impact was on the reputation of sharks. The film’s plot, centred on a rogue great white shark that deliberately targets swimmers in a small coastal town, was a masterclass in suspense. However, it propagated several damaging myths:

- The ‘Rogue Shark’ Theory: The idea that a single shark develops a taste for humans and must be hunted down is a narrative device with little basis in scientific fact. Sharks do not typically stalk specific prey or territories in this manner.

- Sharks as Man-Eaters: The film depicts the shark as a calculating predator. In reality, sharks do not recognise humans as a food source. Most scientific research supports the idea that attacks on humans are cases of mistaken identity (a surfer on a board resembling a seal from below) or investigative bites (where a shark uses its mouth to explore an unfamiliar object), which can tragically be fatal due to the shark’s size and power.

- The Menacing Score: John Williams’ iconic, accelerating score—dun-dun…dun-dun—is now synonymous with impending danger. It conditioned generations to feel a spike of fear at the mere idea of a shark, a psychological response that is hard to disentangle from rational risk assessment.

The Sobering Statistics and Shark Biology

The tragedy in Sydney is a stark reminder that while shark attacks are a real danger, they are exceptionally rare. This incident is believed to be the first fatal attack in New South Wales this year and only the second in Sydney since 1963. The numbers provide crucial context:

- Global fatalities from shark attacks typically number between 5-10 annually.

- The annual risk of death from a shark is estimated to be 1 in 3.7 million.

- Humans pose a far greater threat to sharks than they do to us. It is estimated that 100 million sharks are killed by humans every year, primarily through overfishing and finning, driving many species towards extinction.

Sharks are not the mindless killers of legend but apex predators critical to the health of marine ecosystems. They regulate prey populations and ensure species diversity. Their behaviour is driven by instinct, curiosity, and the need to feed, not by malice.

A Community in Mourning

Beyond the statistics and the movie parallels lies a profound human tragedy. Superintendent Duncan’s press conference highlighted the personal loss, noting the victim was a family man. “We understand he leaves behind a wife and a young daughter… and obviously tomorrow being Father’s Day is particularly critical and particularly tragic,” he said.

The local surfing community, bound by a shared understanding of the ocean’s rhythms and risks, has been deeply shaken. Local surfer and eyewitness Bill Sakula captured the sentiment: “It’s going to send shockwaves through the community. Everyone is going to be a little bit nervous for a while.”

In the wake of the attack, the official response was swift and measured. Beaches were closed, drones deployed, and wildlife experts consulted—a world away from the amateurish frenzy of the Jaws townsfolk. Surf Life Saving NSW CEO Steve Pearce offered “deepest condolences,” a sober acknowledgement of a rare but devastating event.

Fifty years on, Jaws remains a masterpiece of cinema. Yet, the death of Mercury Psillakis serves as a sombre bookend to its anniversary, compelling a re-examination of its legacy. It reminds us that while the film’s monster was a fiction, the ocean is a wild and powerful realm. The true respect for its inhabitants lies not in fear-driven eradication, but in understanding, conservation, and a clear-eyed acceptance of the risks inherent in entering their world. The shadow cast by the great white shark, both on screen and in reality, is long and complex, blending primal fear with a pressing need for preservation.