Imagine a life free of debt, liberated from societal constraints and large mortgages. A growing number of homeowners are seeking out cheaper and more sustainable ways to fund the four walls in which they live

Creative homeowners are ditching the burden of large mortgages in exchange for building their own homes, mortgage-free. From cottages made of cob, a mix of clay, sand and straw, to a wooden house on wheels and cosy homes created from recycled shipping containers, they are exploring a vast range of alternative methods to build a home on a tiny budget.

Fundamentally, it’s a lifestyle choice. Writing in the 1940s, the words of Irish historian Francis Shaw now ring true more than ever: “When truth and beauty and goodness cannot be found in modern civilisation, we are forced to seek for those values in other places … we must retrace our steps to where we strayed from the road.”

In Ireland’s picturesque Enniskeane, West Cork, at The Hollies Centre for Practical Sustainability, cob building courses are attracting a new kind of client: young couples and singletons who may never have attained mortgage approval are looking to lay down their roots unconventionally.

The centre was founded by Ulrike and Thomas Riedmuller, who are advocates of experiential learning. They advise anyone considering a cob build to start at grassroots level: “Start small, build a small cob structure in your garden, like a cob oven, something that will help you get a feel for the method but let you learn from your mistakes before you set about building something more substantial,” says Ulrike Riedmuller.

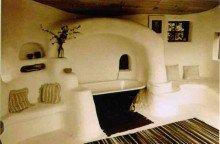

The pair open up their own cob home to course participants and there is also an on-site cob dwelling, which cost just over €1,000 (£864) to build and kit out.

At the courses, students learn about getting the right mix of clay and sand before adding straw for strength. Building blocks called cob loaves are created to mound the structure over a regular foundation rising one to two feet off the ground. The malleable cob loaves are pressed into the foundation to form the walls, often two feet thick, effectively allowing the builder to literally sculpt their own home.

The process is said to be time-consuming but brilliant in its simplicity, with the Riedmuller’s home featuring a composting toilet, solar panels and an ultra energy-efficient wood-burning stove. They have no refrigerator, having built a parlour space into the north-facing wall to store food at cool temperatures. They made use of salvaged materials where possible.

A straw bale build, like cob, is said to offer a cheap alternative to concrete blocks. Rectangular bales can be slotted into wooden frames with relative ease, while thick bales provide excellent insulation and can be fire-treated and plastered over. Plans are available online, instructions for the building process are available on YouTube and there are various support organisations across the UK and the US.

From thick walls, to thin and durable dividers, other imaginative homeowners have turned to shipping containers in an extreme recycling project.

At Trinity Buoy Wharf Jubilee Pier in East London, Container City houses a creative community of residents who are living and working in shipping containers stacked four storeys high. At 20 feet long, the containers offer roughly 45 square metres of living space, which is why some residents choose to stack a second or a third.

This is not just an option for savvy artists seeking alternative lodgings. Container living is a growing option for older parents who have space to house their adult children in their back garden.

There are companies in Europe, the UK, and the US that can convert containers to buyers’ preferred specifications, adding windows, door fittings and floors. Insulation is required however, along with some clever design techniques to offset feelings of claustrophobia.

On the other hand, fans of the Tiny House Movement are embracing confined spaces.

The social movement, born from part necessity and part desire to downsize, covers tiny homes ranging from 75 square feet to 400 square feet of floor space. Clever architectural design makes tiny house living practical and attractive, but in its essence the movement represents freedom: from mortgage debt; maintenance costs; modern consumerism; and the accumulation of unnecessary belongings.

“It’s becoming popular due to economics,” says tiny house owner Noel Higgins. “Tiny houses are cheap to build, low maintenance and exempt from planning. It’s about downsizing generally and a move away from mass consumption. When you live in a small space it forces you to think what you need and don’t need.”

Higgins, 40, built a wooden house on wheels that attracted plenty of interest when featured on the Tiny House Movement Facebook page. Higgins’ self-made 16 x 8ft wooden house on wheels cost €6,000 (£5,182) and took less than two months to construct.

He completed his first winter in his tiny house in 2013, when he encountered over-heating as a problem, rather than the other way around. “I wasn’t really sure how I would adjust to living in a small space, but it’s been an easy transition,” he said.

The movement lays claim to a series of spin-off positive results, such as simplified living, a more environmental conscience, self-sufficiency, greater affordability and a greater social conscience. It is also successfully creating interest in a social trend towards more concentrated spaces, in line with more concentrated means.

The tiny houses can come in a range of forms, with not all falling into the ultra-affordable range. A tiny house can be a log cabin on wheels, a hobbit home built into a hillside or an impressive glass structure situated in picturesque scenery. For those not building on wheels, a plot of land is required, which doesn’t come cheap unless there is someone’s back garden to live in.

But if the desire for financial freedom still bites, the move towards unconventional living may be the key to achieving your dreams.