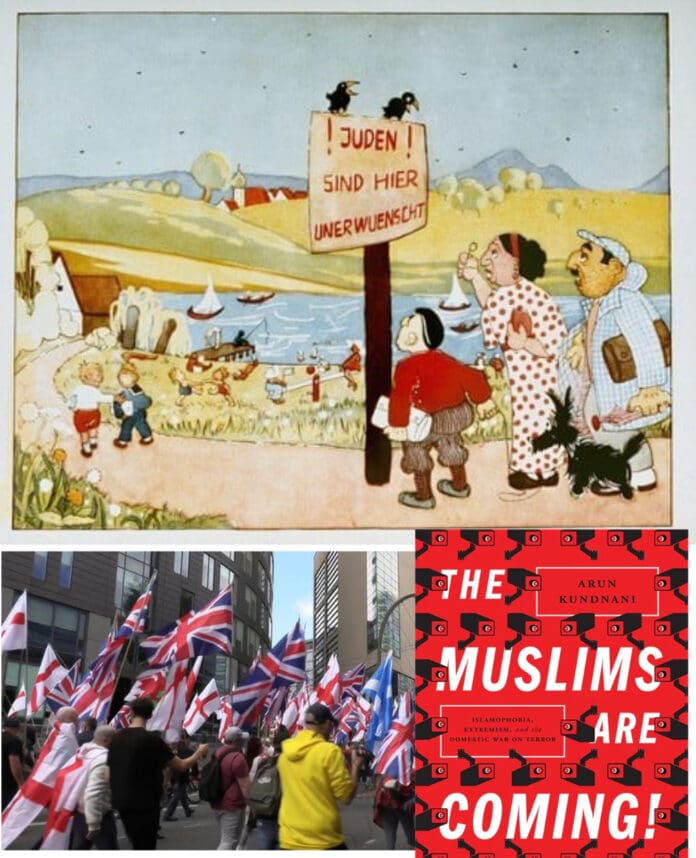

In the 1930s and 40s, hatred of Jews was not just one prejudice among many for Europe’s far right, it was the organising principle. Jews were imagined as both omnipotent and parasitic, orchestrating global conspiracies while corrupting nations from within. This narrative underpinned fascist ideology and culminated in genocide. Today, however, while antisemitism has not disappeared, it no longer defines the far right in quite the same way. For many of its adherents, Muslims have taken centre stage as the primary target of fear and resentment. The old hatred lingers in the background; the new one is louder, more visible, and more politically useful.

The shift didn’t happen overnight. After the Holocaust, open antisemitism became taboo in much of Western Europe. Far-right movements adapted, often grudgingly. In Britain, the National Front and later the BNP still trafficked in Holocaust denial and fantasies of Jewish control, but they discovered that attacks on immigrants, particularly South Asian Muslims, played better with the public. France’s Front National underwent a similar evolution. Jean-Marie Le Pen had flirted with Nazi nostalgia; his daughter Marine learned to speak the language of “cultural preservation,” reserving her sharpest rhetoric for Muslims. This wasn’t tolerance, but strategy.

The post-war immigration wave made that strategy possible. Muslim communities, brought in as labour from former colonies, were more visible than Jews in their cultural and religious expression. Mosques rose where churches stood empty; halal butchers appeared on high streets. Many Muslims settled in poorer urban areas, creating concentrated communities that became easy targets for narratives of segregation and “no-go zones.” Economic inequality fed resentment, but it was cultural difference that the far right seized upon. In this way, Islamophobia became not merely acceptable but mainstream.

Geopolitics accelerated the process. The 1979 Iranian Revolution presented images of chanting crowds denouncing the West. The Rushdie Affair a decade later brought the clash into British streets. Then came 9/11, which delivered the far right a psychological windfall: Muslims could now be cast as not just incompatible but existentially dangerous. By the time the Syrian refugee crisis hit Europe in 2015, parties like Alternative für Deutschland and Hungary’s Fidesz were describing Muslim migration as an “invasion,” a language that would have been politically unthinkable if directed at Jews.

Psychology helps explain why this pivot worked so effectively. Social identity theory suggests that in-group cohesion strengthens when there is a clear, threatening out-group. For much of Europe’s modern history, Jews played that role. But Muslims are now perceived as both a visible presence and a symbolic enemy, linked to conflicts abroad and social changes at home. Fear conditioning amplifies this effect: each terrorist attack, though statistically rare, imprints itself deeply on public consciousness, especially when replayed in endless loops on television and social media.

Projection also plays a role. Far-right groups often accuse Muslims of precisely the behaviours they fear in themselves: intolerance, expansionism, the desire to impose values by force. The charge of “cultural takeover” says more about the accuser’s anxieties than about any objective threat. And yet, in the minds of extremists, these ideas gain moral weight when presented as defensive rather than aggressive. Supporting Israel, for example, is recast not as solidarity with Jews but as pragmatic alignment in a civilisational war.

This reasoning surfaced when I met “Alex” and “Micky,” two Englishmen in their thirties who drifted from football hooliganism into far-right activism. They agreed to talk on the condition of anonymity.

“You can see it happening,” Alex said, gesturing to the row of halal shops on the high street. “Mosques going up, women in veils. It’s like watching your country slip away.”

Micky leaned in. “And Muslims bring fear. Bombings, grooming gangs. It’s in your face. With Jews it’s about shady deals behind the scenes. But Muslims? They’re changing the streets.”

I asked about their vocal support for Israel’s military campaign in Gaza, a stance that seemed at odds with their complaints about “globalist elites,” a phrase often used as a stand-in for antisemitic conspiracy. Alex didn’t flinch. “Because they’re doing what we can’t—pushing back,” he said. “We don’t have to like Jews to see they’re on our side this time.”

Micky smirked. “Sort the Muslim problem first. After that, we’ll see who’s really pulling the strings.”

Their words captured the psychological knot: Muslims as the urgent enemy, Jews as the useful one. Instrumental morality, supporting those you still distrust because they fight the enemy you fear more, allows contradictory prejudices to coexist without tension.

Polling data reflects this shift. The European Social Survey in 2018 found that over 40% of respondents in some Western European countries believed Muslims were “incompatible with Western values,” while antisemitic attitudes hovered at lower but persistent levels. Pew Research in 2016 noted that spikes in anti-Muslim sentiment corresponded to moments of crisis, terrorist attacks, and refugee movements, while antisemitism remained steadier, embedded in conspiracy theories but less central to public discourse. Fear of cultural change, not economic stress, emerged as the strongest predictor of Islamophobia.

Online ecosystems have turbocharged these dynamics. Social media algorithms reward outrage, pushing sensational stories about Muslim violence to the top of feeds. Telegram channels and 4chan boards blend antisemitism and Islamophobia into a single narrative: Jews are accused of orchestrating Muslim immigration to weaken Europe, while Muslims are portrayed as the foot soldiers of that supposed plot. Even memes, shared half-jokingly, become carriers of hate. Irony provides cover, allowing bigotry to spread under the guise of humour.

France offers a stark illustration of how these narratives embed themselves. Marine Le Pen’s National Rally now claims to defend Jews against “Islamist antisemitism,” yet antisemitic conspiracy theories flourish among her supporters online. Hungary’s Viktor Orbán demonises Muslim migrants as invaders while simultaneously attacking George Soros as the puppet master behind global destabilisation. The United Kingdom’s far right has followed the same script: the BNP’s fixation on Jewish control gave way to the English Defence League and Britain First’s anti-Muslim street marches, even as its forums hosted Holocaust denial.

None of this is inevitable. Prejudice is malleable, though rarely eliminated without effort. Contact between groups has been shown to reduce hostility, but only when it goes beyond token gestures—when people work together on shared goals. Media narratives matter, too: disproportionate coverage of Muslim-linked violence reinforces fear, while stories of solidarity disrupt it. Online, interventions that break algorithmic cycles of outrage could blunt the spread of extremist content, though this requires regulation that platforms have so far resisted.

The deeper challenge lies in dismantling the psychological mechanisms that keep the hierarchy of hate intact. As long as fear and projection remain politically useful, the far right will find someone to fill the role of “enemy.” Today it is Muslims; yesterday it was Jews; tomorrow it may be someone else entirely. The target shifts, but the underlying machinery—the need for scapegoats and the myths of purity and invasion—remains the same.

Suggested Reading

- Mark Mazower, Hitler’s Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe (2008) — An authoritative account of how antisemitism was central to Nazi ideology and governance.

- Robert S. Wistrich, A Lethal Obsession: Anti-Semitism from Antiquity to the Global Jihad (2010) — Explores the persistence of antisemitism across history and its modern manifestations.

- Cas Mudde, The Far Right Today (2019) — A clear analysis of contemporary far-right movements in Europe and the United States.

- Jocelyne Cesari, Islamophobia in the West: Measuring and Explaining Trends (2017) — A detailed sociological study of anti-Muslim prejudice and its causes.

- Umberto Eco, “Ur-Fascism” (1995, essay) — A concise list of the psychological and political features common to fascist movements, useful for understanding how hate persists.

- Jonathan Haidt, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion (2012) — Insightful psychological perspectives on group identity and moral reasoning.

- Sarah Hunt and Graham Macklin (eds), Contemporary Far-Right Extremism (2017) — A collection of essays on far-right ideologies, including analysis of Islamophobia and antisemitism.

- European Social Survey, 2018 — For data on public attitudes towards Muslims and Jews in Europe.

- Pew Research Centre, “Europe’s Growing Muslim Population” (2017) — Polling data showing trends in public opinion and demographic change.