John Peel, born John Robert Parker Ravenscroft on 30 August 1939, was a pioneering radio DJ whose influence on British music can hardly be overstated. For nearly 40 years, his BBC Radio 1 show was a vital source of discovery for generations of listeners, and his advocacy for new and unconventional music helped shape the tastes of millions. With an ear for innovation and a fearless disregard for convention, Peel introduced audiences to everything from punk to reggae, hip-hop to electronic music, bringing underground genres into mainstream awareness. He did more than play records; he crafted a space for emerging sounds and voices. Reflecting on his own ethos, Peel once stated, “I just want to hear something I haven’t heard before,” and in doing so, he opened doors for thousands of bands and set the standard for what music broadcasting could achieve.

Peel’s early life was unconventional, fitting for someone who would go on to become a rebel against musical norms. He grew up in Heswall on the Wirral, where his father, a cotton broker, encouraged a career in industry rather than music. But from an early age, Peel’s attraction to radio and recorded sound was unmistakable. As a teenager, he attended Shrewsbury School, an experience he described as “bloody awful” but essential to his development. It was in the small spaces of radio broadcasts that Peel found solace, discovering American rock’n’roll and R&B that sounded unlike anything he had heard in Britain at the time.

After completing National Service, he emigrated to the United States, where he initially worked in the cotton business before turning to radio in Dallas. There, he developed his skills as a DJ on the airwaves, championing the British Invasion of the mid-1960s, and experiencing firsthand the power that music had to galvanise listeners. While in Dallas he witnessed the fatal shooting of Lee Harvey Oswald by Jack Ruby, who was in custody following the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Returning to Britain in 1967, he joined the BBC’s newly formed Radio 1, marking the start of a career that would transform the cultural landscape of British music. Peel’s shows quickly became synonymous with musical discovery, as he devoted himself to tracking down unknown or unusual records, particularly from artists ignored by mainstream radio.

One of Peel’s most celebrated qualities was his talent for spotting potential in bands long before anyone else noticed them. His ear for novelty, his openness to unconventional styles, and his passion for live performances were key. Bands as iconic as The Smiths, Joy Division, The Undertones, and Pulp owed their initial airplay to Peel, who saw in their raw sounds a spark that commercial broadcasters missed. “He just played what he liked,” recalls Robert Smith of The Cure, who found early support from Peel. “He didn’t care about being trendy or cool; he cared about the music and nothing else.”

Peel’s dedication to music discovery took on a ritualistic quality with his famous Peel Sessions, live studio recordings by bands invited to perform exclusively for his show. The sessions became legendary in their own right, often capturing artists at a crucial stage in their development. Joy Division’s sessions with Peel are particularly memorable, as they showcased a sound that was haunting, melancholic, and distinctly ahead of its time. The session versions of “Transmission” and “Love Will Tear Us Apart” are still held in high regard, representing the raw, visceral energy Peel sought in every band he played. Joy Division’s manager, Tony Wilson, once said of Peel, “He could hear the future in a way that no one else could. Without Peel, there would have been no Joy Division as we know it.”

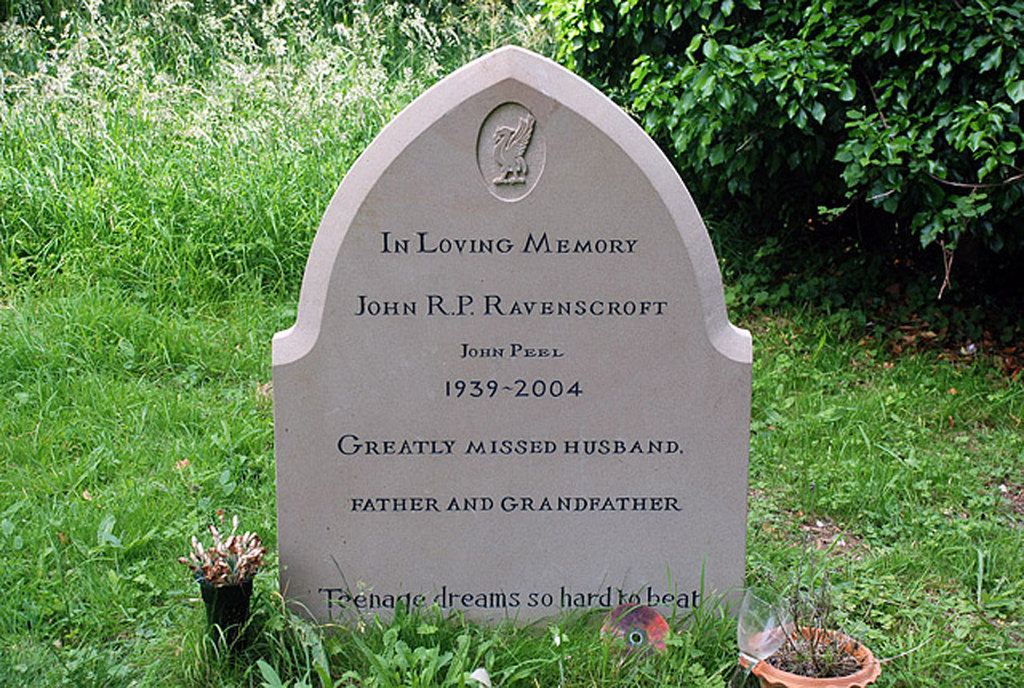

For punk rock, Peel’s impact was seismic. He was instrumental in bringing bands like The Clash, The Sex Pistols, and The Buzzcocks to a wider audience, supporting a movement that would radically challenge British society. To Peel, punk represented a return to the urgency and passion he had heard in American rock’n’roll, and he championed it accordingly. “Punk felt like the sound of liberation,” Peel remarked in a later interview. “It wasn’t polished; it was immediate, and that was what made it exciting.” His broadcasts of tracks like The Undertones’ “Teenage Kicks” would go down in history. When he first heard it, he famously claimed it was his favourite song ever, saying, “Nothing you can do in life can bring you the pleasure that listening to that song does.”

His work did not stop with punk; Peel was an early supporter of reggae and dub, styles almost entirely ignored by other British broadcasters at the time. The impact was immense: songs by Augustus Pablo, King Tubby, and Lee “Scratch” Perry reached British audiences who had never heard anything like them. Peel’s enthusiasm for reggae also extended to ska and rocksteady, introducing people to the sounds of Jamaican culture and music. The Clash’s reggae-influenced “Police and Thieves” was one of many tracks Peel championed, and his support for reggae persisted long after punk waned, showcasing his commitment to music that remained marginalised or misrepresented.

In the 1980s, Peel embraced the new wave and post-punk scenes, showcasing artists like The Fall, Siouxsie and the Banshees, and Echo & the Bunnymen, who experimented with darker, more atmospheric sounds. The Fall, in particular, became closely associated with Peel, who invited them for over 20 Peel Sessions, more than any other band. Mark E. Smith, the band’s notoriously cantankerous frontman, was both a challenge and a delight for Peel, who enjoyed Smith’s singular approach to songwriting and his disregard for conventional fame. The relationship between Peel and The Fall became legendary, with Peel describing Smith’s lyrics as “like news from a foreign country.” The Fall’s “Totally Wired” and “New Face in Hell” are emblematic of Peel’s preference for music that refused to sit comfortably in the mainstream.

Peel’s love of new music never waned, and by the 1990s, he had already set his sights on electronic music and hip-hop, genres that were often viewed with suspicion by other broadcasters. His show played tracks by Public Enemy, A Tribe Called Quest, and later, Aphex Twin and Orbital, pushing these sounds into the limelight. The emerging rave and electronic music scenes of the late ’80s and early ’90s found in Peel an advocate who recognised the creative potential of producers like The Prodigy, Underworld, and The Chemical Brothers. His willingness to embrace the experimental was undeterred, and his Radio 1 broadcasts became a meeting point for listeners of every musical persuasion.

Peel was also known for his humility and modesty, an attitude that allowed him to connect with his audience on a personal level. His candid style, dry humour, and warmth came through in every broadcast. He often shared stories about his family, particularly his wife Sheila—affectionately known as “the Pig”—and his four children. Despite his extensive music knowledge and influence, Peel was self-deprecating to a fault, often downplaying his contributions to music, insisting he was merely “a fan with a microphone.” This unpretentious nature endeared him to millions, creating a sense of intimacy between him and his audience. Peel’s authenticity was palpable; he felt more like a friend than a radio personality, a feeling summed up by one listener who wrote, “It was like being let into a wonderful secret every night.”

While Peel championed an eclectic array of genres and movements, he never abandoned his roots, often revisiting early favourites like Captain Beefheart and The Velvet Underground. His appreciation for experimental and avant-garde music persisted, with him often describing records that others dismissed as noise as “challenging.” The familiar sound of Peel chuckling at records that “sounded like a man being sick” became an enduring aspect of his broadcasts. However, he always listened with an open mind, a trait few broadcasters shared. As he once explained, “If I play something that makes me laugh because it’s so strange, that’s usually a sign it’s worth hearing.”

John Peel died suddenly on 25 October 2004 while on holiday in Peru, leaving behind a legacy that few in music broadcasting could hope to match. His death was a tremendous loss, not only to his family and friends but to the thousands of artists he championed and the countless fans he introduced to new music. Musicians, fans, and colleagues shared their grief, and tributes poured in from every corner of the music world. David Bowie called him “an innovator” and “a true champion of music,” while Radiohead’s Thom Yorke expressed a collective sentiment, stating simply, “We are all going to miss him.” Peel’s loss was felt deeply by listeners who had grown up with his voice, finding in his shows a place of refuge and exploration.

For the many artists Peel supported, his influence endures. Bands like The White Stripes, who recorded Peel Sessions long after his initial wave of discoveries, cite him as instrumental to their careers. Jack White once commented, “There were no walls with John Peel; he just wanted to get down to what was real.” This openness and lack of judgement allowed Peel to foster music that otherwise might have been forgotten, giving space to young, unpolished talent and letting them find their voice in his studio.

Peel’s record collection, a vast and meticulously catalogued library, became a symbol of his dedication to music. It housed everything from 7-inch punk singles to obscure African records, experimental noise tapes, and hip-hop vinyl, offering a glimpse into the diversity that defined his taste. The collection, lovingly preserved by his family, has become a resource and a testament to the breadth of his impact, symbolising a lifetime spent in service to music and its power to connect people.

Ultimately, John Peel’s legacy is one of fearlessness and passion. His shows were a place where boundaries ceased to exist, where a reggae song could follow a punk track, where electronic sounds intermingled with indie guitar riffs, and where fans from all walks of life tuned in, trusting that he would play something worth hearing. His commitment to authenticity, his relentless search for the unknown, and his unwavering support for every underdog in music made him more than a DJ; he was a cultural icon who embodied the spirit of independent, open-minded creativity.

In the words of Peel himself, “I’ve always felt that if you don’t like a particular record, the best thing to do is to wait for three minutes because there’s probably something coming along that you might enjoy.” His approach to music as an endless, evolving conversation remains a model for broadcasters and a beacon for fans who believe in the power of sound to challenge, inspire, and unite. And for that, John Peel will be remembered as the voice that brought music into the lives of millions, one track at a time, with unwavering passion and an ear for the extraordinary.