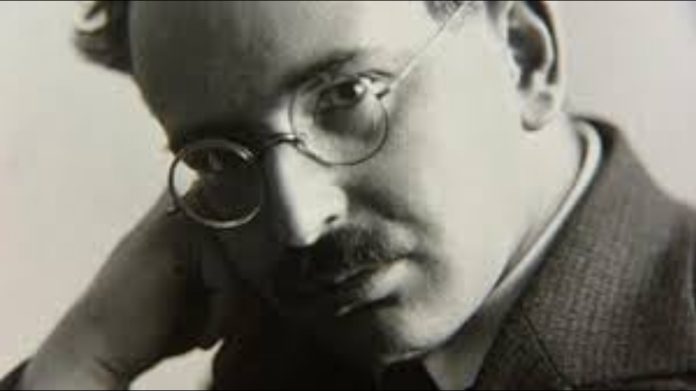

Walter Benjamin was one of the most original and influential thinkers of the 20th century. A philosopher, cultural critic, and literary theorist, Benjamin’s work spans an extraordinary range of subjects, including aesthetics, history, language, technology, and the relationship between art and politics. His life, however, was marked by struggle, displacement, and tragedy, culminating in his untimely death in 1940 as he attempted to flee Nazi-occupied France. Despite his personal and political hardships, Benjamin left behind a body of work that continues to shape our understanding of modern capitalist society and its impact on culture, art, and history.

Born in Berlin on July 15, 1892, into a wealthy Jewish family, Benjamin’s early life was shaped by the tensions of being an intellectual in Wilhelmine Germany. He attended the prestigious Kaiser Friedrich School in Charlottenburg, where he was deeply influenced by Romantic and Idealist thinkers like Goethe and Kant, as well as the philosophy of life that dominated the German intellectual scene at the time. After briefly studying at the University of Freiburg, Benjamin moved to Berlin, where he became involved with the German Youth Movement, a left-wing intellectual circle that challenged the conservative, militaristic values of the German Empire.

During his time at university, Benjamin became increasingly interested in the philosophy of language and the theory of literature, which would become central themes in his later work. He wrote his doctoral thesis on the early German Romantic poet Friedrich Hölderlin and attempted to obtain a university position. However, his inability to secure a stable academic job due to his unorthodox ideas and his Jewish background led him to pursue a more independent intellectual path. His frustrations with academia were mirrored by his growing political radicalism, which would eventually draw him into the orbit of Marxism and the Frankfurt School of Critical Theory.

One of Benjamin’s most important early works was The Task of the Translator (1923), an essay in which he explored the relationship between translation, meaning, and the original work of art. In this essay, Benjamin argued that the role of the translator is not simply to transmit the content of a text from one language to another, but to “liberate the language imprisoned in a work in his re-creation of that work” (Benjamin, 1923). For Benjamin, translation was a form of artistic creation in its own right, capable of revealing the hidden meanings of a text and creating a dialogue between different cultures. This idea of art as a form of emancipation, capable of challenging dominant modes of thinking and revealing alternative possibilities, would become a recurring theme in Benjamin’s later work.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Benjamin wrote on a wide range of subjects, often focusing on how cultural forms like literature, art, and technology are shaped by the material conditions of society. His engagement with Marxism, particularly through his friendship with Bertolt Brecht and his connections to the Frankfurt School, deepened his understanding of how capitalism affects culture and consciousness. In his famous essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935), Benjamin examined the effects of technological reproduction—particularly photography and film—on the traditional concept of art. This work is one of Benjamin’s most celebrated contributions to critical theory and continues to shape how we understand the role of art in modern society.

In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Benjamin argued that the development of technologies capable of mechanically reproducing works of art—such as the camera and the printing press—fundamentally altered the nature of art. In traditional societies, art was closely tied to rituals and religious practices, and each work of art possessed what Benjamin called an “aura”—a unique presence in time and space that made it special and unrepeatable. However, with the advent of modern reproduction technologies, this aura was lost, as artworks could now be mass-produced and widely disseminated. The aura’s destruction, according to Benjamin, had both positive and negative implications.

On one hand, the loss of aura meant that art could no longer be used to uphold the authority of religious or political elites. As Benjamin put it, “Mechanical reproduction emancipates the work of art from its parasitical dependence on ritual” (Benjamin, 1935). The reproducibility of art opened up new possibilities for critical engagement with society, as more people could access and interpret works of art independently of the traditional hierarchies that had previously controlled their meaning. Art, in this sense, became democratized, capable of challenging the status quo and inspiring revolutionary thought.

On the other hand, Benjamin was deeply concerned that the commodification of art under capitalism would undermine its potential for radical critique. As art became more widely reproduced, it also became more subject to the forces of the marketplace, where it was increasingly treated as a commodity to be bought and sold rather than as a medium for political or spiritual reflection. The culture industry, as it developed under capitalist conditions, often turned art into a form of entertainment, stripping it of its critical potential and using it to pacify the masses. In this respect, Benjamin shared the concerns of his colleagues Adorno and Horkheimer, who argued that the culture industry played a key role in maintaining the ideological dominance of capitalism by turning art into a tool for social control.

While Benjamin was concerned about the commodification of art, he also recognised the revolutionary potential of new media forms like film and photography. Unlike traditional forms of art, which required passive contemplation, film demanded active engagement from its audience. The fragmented and fast-paced nature of cinematic images reflected the fragmented nature of modern experience and could, under the right conditions, provoke critical thinking about society. As Benjamin wrote, “The film responds to the shrivelling of the aura with an artificial build-up of the ‘personality’ outside the studio” (Benjamin, 1935). Film, according to Benjamin, could challenge the bourgeois notion of art as a timeless, contemplative experience and instead engage the viewer in a dynamic, politicized encounter with reality.

In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Benjamin foresaw both the dangers and possibilities of modern mass media. He recognised that, under capitalism, media technologies could be used to manipulate and control the masses, but he also believed that these technologies contained the seeds of their own subversion. By breaking down traditional hierarchies of meaning and authority, modern media could open up new spaces for critical thought and revolutionary action. This dialectical approach to technology and culture is one of the hallmarks of Benjamin’s thought and reflects his broader attempt to reconcile Marxism with his earlier, more metaphysical concerns.

While The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction remains one of Benjamin’s most influential works, his writings on history and time are perhaps even more radical in their implications. In his final work, Theses on the Philosophy of History (1940), Benjamin offers a profound critique of the Enlightenment idea of progress, which he saw as deeply complicit in the violence and exploitation of capitalist modernity. For Benjamin, history is not a linear, teleological process leading inevitably to a better future, but a series of ruptures and catastrophes, where the suffering of the oppressed is continually repressed and forgotten.

In Theses on the Philosophy of History, Benjamin introduces the image of the “Angel of History,” an evocative metaphor that captures his pessimistic view of historical progress. The Angel, based on a painting by Paul Klee, looks back at the past with horror, seeing not a chain of events leading to human progress but a “pile of debris” left in the wake of countless injustices and atrocities. Benjamin writes:

“A Klee painting named ‘Angelus Novus’ shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress” (Benjamin, 1940).

This image encapsulates Benjamin’s critique of progress, which he believed served as an ideological justification for the continuation of capitalist exploitation and oppression. For Benjamin, history was not the story of human advancement but a series of violent ruptures, where the hopes and struggles of the oppressed were continually crushed. In contrast to the optimistic belief in progress that characterised much of Enlightenment thought, Benjamin saw history as a site of constant conflict, where the possibility of liberation was always threatened by the forces of domination.

However, Benjamin did not entirely abandon the idea of historical change. He believed that within moments of crisis and rupture, there were opportunities for revolutionary transformation. In his concept of “Jetztzeit” or “now-time,” Benjamin argued that history contains moments where the past and present come into a dialectical relationship, revealing the possibility of revolutionary change. The task of the historian, according to Benjamin, was not simply to document the past but to uncover these moments of potential rupture and use them to challenge the dominant narrative of progress. In this sense, Benjamin’s philosophy of history is both deeply pessimistic and radically hopeful, as it emphasises the importance of seizing the present moment in order to transform the future.

Benjamin’s concern with history and time is also reflected in his unfinished magnum opus, The Arcades Project (1927–1940), a sprawling and fragmented work that explores the cultural and social history of 19th-century Paris. Using the Parisian arcades—covered shopping streets that were early sites of consumer culture—as a lens through which to examine the development of modern capitalism, Benjamin sought to uncover the hidden forces shaping modern life. The arcades, with their displays of commodities and their architecture of glass and steel, represented for Benjamin the fetishistic nature of capitalist society, where commodities are imbued with mystical qualities and human relations are mediated by objects.

At the same time, The Arcades Project is a work of political theory, as Benjamin sought to reveal how the material conditions of capitalist society shape consciousness and perception. He was particularly interested in the figure of the flâneur—the urban wanderer who moves through the city, observing its sights and sounds but remaining detached from its commercial and political life. For Benjamin, the flâneur embodied both the alienation and the critical potential of modern urban experience. The flâneur’s gaze, detached and contemplative, allowed him to see through the surface of capitalist society and reveal its contradictions and tensions.

Benjamin’s interest in the flâneur and the arcades reflects his broader concern with how capitalism shapes perception and experience. In modern capitalist societies, where commodities dominate social relations, human beings become alienated from their own experiences, which are mediated by the market. However, Benjamin believed that within the alienation of modern life lay the potential for critical consciousness. The fragmented, disorienting experience of modernity, particularly in the urban environment, could provoke new ways of seeing and thinking that might inspire revolutionary action.

As Benjamin’s work developed, his political and intellectual commitments became increasingly urgent in the face of the rise of fascism in Europe. A committed anti-fascist, Benjamin saw the dangers posed by the totalitarian regimes of Hitler and Mussolini as the logical extension of capitalist domination. In his view, fascism represented the aestheticization of politics, where the masses were mobilised through spectacle and propaganda rather than through genuine political engagement. As he famously wrote in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, “All efforts to render politics aesthetic culminate in one thing: war” (Benjamin, 1935). Benjamin believed that under fascism, art and politics became indistinguishable, as both were used to manipulate the masses and glorify violence.

Benjamin’s commitment to revolutionary thought and his opposition to fascism ultimately led to his tragic death. As a Jewish intellectual with Marxist sympathies, Benjamin was forced to flee Germany after the rise of the Nazis in 1933. He spent much of the next several years in exile, moving between Paris and various other European cities, often struggling to support himself financially. In 1940, with the Nazi occupation of France imminent, Benjamin attempted to escape across the border into Spain with a group of other refugees. However, when the group was denied passage by Spanish authorities, Benjamin, fearing that he would be handed over to the Nazis, took his own life on the night of September 26, 1940, in the small Catalonian town of Portbou.

Despite the tragic circumstances of his death, Benjamin’s intellectual legacy endures. His writings offer profound insights into the nature of capitalist society, the role of art and culture in shaping consciousness, and the possibilities for revolutionary change. By challenging the dominant narratives of progress and history, Benjamin’s work continues to inspire critical thought and political action, offering us new ways of understanding the world and our place within it. His life and death, marked by struggle and displacement, reflect the tumultuous times in which he lived, but his ideas remain as relevant as ever in our own age of crisis and transformation.