Since the EU referendum hate crime has dramatically risen. Many people feel more enabled to be hateful but thankfully many more people are reporting it. As a consequence many more are being convicted. Wherever we see it, report it, and get these vile individuals punished.

Key results

- in year ending March 2022, there were 155,841 hate crimes recorded by the police in England and Wales, a 26 per cent increase compared with the previous year

- this was the biggest percentage increase in hate crimes since year ending March 2017, when there was a 29 per cent rise

- due to significant improvements in police recorded crime made in recent years, it is uncertain to what degree the increase in police recorded hate crime is a genuine rise, or due to continued recording improvements and more victims having the confidence to report these crimes to the police

- as in previous years, the majority of hate crimes were racially motivated, accounting for over two-thirds of such offences (70%; 109,843 offences); these types of hate crime increased by 19 per cent between year ending March 2021 and year ending March 2022

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

This statistical bulletin provides information on the number of hate crimes recorded by the police in England and Wales in year ending March 2022.

Police forces have made significant improvements in how they record crime since 2014. They have also improved their identification of what constitutes a hate crime. Because of these changes, police recorded crime figures do not currently provide reliable trends in hate crime. The figures do, however, provide a good measure of the hate crime-related demand on the police. For more information, see Section 3: Police recorded hate crime data sources and quality.

1.2 Hate crimes recorded by the police

Hate crime is defined as ‘any criminal offence which is perceived, by the victim or any other person, to be motivated by hostility or prejudice towards someone based on a personal characteristic.’ This common definition was agreed in 2007 by the police, Crown Prosecution Service, Prison Service (now the National Offender Management Service) and other agencies that make up the criminal justice system. There are five centrally monitored strands of hate crime:

- race or ethnicity

- religion or beliefs

- sexual orientation

- disability, and

- transgender identity

In the process of recording a crime, the police can flag an offence as being motivated by one or more of these five monitored strands [footnote 1] (for example, an offence can be motivated by hostility towards the victim’s race and religion). For more information, see Section 4 – Hate Crime data sources and quality. Hate crime figures in this bulletin are therefore dependent on a flag being correctly applied to an offence that is identified as a hate crime.

The College of Policing (CoP) published updated guidance on how the police should respond to hate crime in October 2020. The Authorised Professional Practice guidance on hate crime includes information on what can be covered by hate crime. The guidance states:

A hate crime is any criminal offence which is perceived by the victim or any other person to be motivated by a hostility or prejudice based on:

- a person’s race or perceived race, or any racial group or ethnic background including countries within the UK and Gypsy and Traveller groups; this includes asylum seekers and migrants

- a person’s religion or perceived religion, or any religious group including those who have no faith

- a person’s sexual orientation or perceived sexual orientation, or any person’s sexual orientation

- a person’s disability or perceived disability, or any disability including physical disability, learning disability and mental health or developmental disorders

- a person who is transgender or perceived to be transgender, including people who are transsexual, transgender, cross dressers and those who hold a Gender Recognition Certificate under the Gender Recognition Act 2004

The inclusion of migrants within the first category listed above means that offences with a xenophobic element (such as graffiti targeting certain nationalities) can be recorded as race hate crimes by the police.

An offence may also be motivated by hatred towards a characteristic (strand) that is not currently centrally monitored and therefore does not form part of the data collection presented in this statistical bulletin (age or gender for example).

Hate crimes are taken to mean any crime where the perpetrator’s hostility or prejudice against an identifiable group of people is a factor in determining who is victimised. While a crime may be recorded as a ‘hate crime’, it may only be prosecuted as such if evidence of hostility is submitted as part of the case file.

Terrorist offences may or may not be considered a hate crime depending on the circumstances. A terrorist attack may be targeted against general British or Western values rather than one of the five specific strands. Attacks of this nature are therefore not covered by this statistical bulletin, although they will clearly be motivated by hate. However, other terrorist attacks are motivated by a hatred towards one of the centrally monitored hate crime strands covered by this statistical bulletin. For example, the Finsbury Park Mosque attack in June 2017 has been classified as a hate crime because the victims were thought to be targeted because of their religious affiliation.

The Law Commission published recommendations in December 2021 to reform hate crime laws to remove the disparity in the way hate crime laws treat each protected characteristic – race, religion, sexual orientation, disability and transgender identity. These recommendations by the Law Commission may lead to future changes in the future coverage of the monitored strands. The report can be found here: Hate crime laws: Final report – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

1.3 Hate crimes and racially or religiously aggravated offences

There are some offences in the main police recorded crime collection which have specific racially or religiously motivated elements defined by statute. These constitute a set of offences which are distinct from their non-racially or religiously aggravated equivalents (the full list of these is shown in Table 1.1). These racially or religiously aggravated offences are, by definition, hate crimes. Half (49%) of hate crime offences were recorded as one of these racially or religiously aggravated offences.

Table 1.1 The five racially or religiously aggravated offences and their non-aggravated equivalents

| Racially or religiously aggravated offences | Non-aggravated equivalent offences | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Offence code | Offence description | Offence code | Offence description |

| 8P | Racially or religiously aggravated assault with injury | 8N | Assault with injury |

| 105B | Racially or religiously aggravated assault without injury | 105A | Assault without Injury |

| 8M | Racially or religiously aggravated harassment | 8L | Harassment |

| 9B | Racially or religiously aggravated public fear, alarm or distress | 9A | Public fear, alarm or distress |

| 58J | Racially or religiously aggravated criminal damage | 58A 58B 58C 58D | Criminal damage to a dwelling Criminal damage to a building other than a dwelling Criminal damage to a vehicle Other criminal damage |

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office

1.4 Crime survey for England and Wales (CSEW)

The CSEW is a face-to-face victimisation survey and also provides information on hate crimes experienced by people resident in England and Wales. However, the size of the CSEW sample means the number of hate crime incidents and victims estimated in a single survey year is too unreliable to report on. Therefore, three annual datasets are combined to provide a larger sample which can be used to produce robust estimates for hate crime. Estimates from the survey were last published in ‘Hate Crime, England and Wales, 2019 to 2020’. The next publication of figures from the CSEW would have been due in 2023, but this will be delayed because the face-to-face survey was suspended due to public health restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Police recorded hate crime

Key results

- in year ending March 2022, there were 155,841 hate crimes recorded by the police in England and Wales, an increase of 26% from year ending March 2021 (124,104 offences)

- there were 109,843 race hate crimes, 8,730 religious hate crimes, 26,152 sexual orientation hate crimes, 14,242 disability hate crimes and 4,355 transgender hate crimes in year ending March 2022

- there were annual increases in all five strands of hate crime, ranging from 19% for race hate crimes to 56% for transgender hate crimes

- the upward trend in hate crime seen in recent years is likely to have been mainly driven by improvements in crime recording by the police; there have been spikes in hate crime following certain events such as the EU Referendum and the terrorist attacks in 2017

- it is uncertain the extent to which the increases seen this year continue the pattern of improvements in police recording or represent a real increase in hate crime; the rise seen in the latest year may also have been affected by the lower levels of crime recorded in year ending March 2021 due to the COVID 19 pandemic restrictions; trends may also differ by strand as some crime types have been more affected by improvements in recording practices than others

- as in previous years, the majority of hate crimes were racially motivated, accounting for over two-thirds of all such offences (70%; 109,843 offences); racially motivated hate crimes increased by 19 per cent between year ending March 2021 and year ending March 2022

- religious hate crimes increased by 37 per cent (to 8,730 offences), up from 6,383 in the previous year; this was the highest number of religious hate crimes recorded since the time series began in year ending March 2012

- sexual orientation hate crimes increased by 41% (to 26,152), disability hate crimes by 43% (to 14,242) and transgender identity hate crimes by 56% (to 4,355); these percentage increases were much higher than seen in recent years

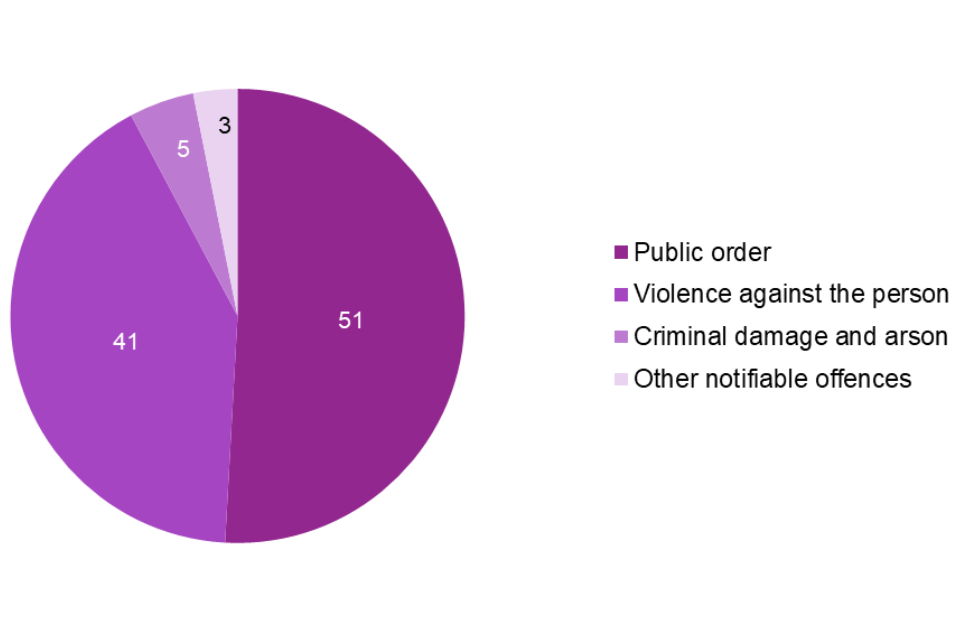

- over half (51%) of the hate crimes recorded by the police were for public order offences and a 41% were for violence against the person offences; five per cent were recorded as criminal damage and arson offences

2.1 Prevalence and trends

Hate crimes are a subset of notifiable offences recorded by the police. In year ending March 2022, three per cent of such offences recorded by the police were identified as being hate crimes. This proportion has gradually increased from one per cent in year ending March 2013, as the police have improved their identification of what constitutes a hate crime, especially across public order and violence against the person offences which account for 92 per cent of hate crime offences collectively.

There were 155,841 hate crimes recorded by the police in England and Wales in year ending March 2022, an increase of 26 per cent compared with year ending March 2021 (124,104 offences; see Table 2.1). All five strands were standing at their highest annual totals since the data were first collected by the Home Office in year ending March 2012.

Table 2.1: Hate crimes recorded by the police by monitored strand, year ending March 2018 to year ending March 2022[footnote 2]

| Numbers and percentages | England and Wales | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hate crime strand | 2017/18 | 2018/19 | 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | % change 2020/21 to 2021/22 |

| Race | 71,264 | 78,906 | [x] | 92,063 | 109,843 | 19 |

| Religion | 8,339 | 8,559 | [x] | 6,383 | 8,730 | 37 |

| Sexual orientation | 11,592 | 14,472 | [x] | 18,596 | 26,152 | 41 |

| Disability | 7,221 | 8,250 | [x] | 9,945 | 14,242 | 43 |

| Transgender | 1,703 | 2,329 | [x] | 2,799 | 4,355 | 56 |

| Total number of motivating factors | 100,119 | 112,516 | [x] | 129,786 | 163,322 | 26 |

| Total number of offences | 94,115 | 106,458 | 114,421 | 124,104 | 155,841 | 26 |

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office.

Notes:

- Total number of offences in year ending March 2020 includes estimated figures for GMP as they were unable to supply data for year ending March 2020 following the implementation of a new IT system in July 2019.

- See Bulletin Table 2 for detailed footnotes.

It is possible for a crime to have more than one motivating factor (for example an offence may be motivated by hostility towards both the victim’s race and religion). Thus, as well as recording the overall number of hate crimes, the police also collect data on the number of motivating factors by strand as shown in Table 2.1. For this reason, the sum of the five motivating factors in the above exceeds the 155,841 overall hate crime offences recorded by the police. Five per cent of hate crime offences in year ending March 2022 were estimated to have involved more than one motivating factor[footnote 3].

As in previous years, race hate crimes accounted for a majority of police recorded hate crimes (70%; 109,843 offences). These offences increased by 19% compared with the previous year (92,063).

Religious hate crimes increased by 37 per cent between year ending March 2021 and year ending March 2022 (from 6,383 to 8,730). This increase follows two years where the number of these offences had fallen.

Sexual orientation hate crimes rose by 41 per cent (from 18,596 to 26,152 offences). This was the largest percentage annual increase in these offences since the time series began in year ending March 2012.

Disability hate crimes increased by 43 per cent (from 9,945 to 14,242) over the last year, the largest percentage annual increase seen since year ending March 2017 (53%).

Transgender identity hate crimes rose by 56 per cent (from 2,799 to 4,355) over the same period, the largest percentage annual increase in these offences since the series began. Transgender issues have been heavily discussed on social media over the last year, which may have led to an increase in related hate crimes.

The recent annual increases seen in hate crime in recent years were thought to have been driven by improvements in crime recording by the police following a review by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS)[footnote 4] in 2014 and the removal of the designation of police recorded crime as National Statistics[footnote 5]. It also thought that growing awareness of hate crime is likely to have led to improved identification of such offences. It is difficult to assess whether the increase in the last year is a continuation of this trend, or whether the rise in hate crime is, in at least part, genuine.

The annual percentage changes seen over the last year across the five strands were partly due to the lower levels of crime recorded by the police in the year ending March 2021 comparison year due to the suppressant effect of the public health restrictions in place during the COVID 19 pandemic, as highlighted in the Crime in England and Wales Statistical bulletins published by the Office for National Statistics.

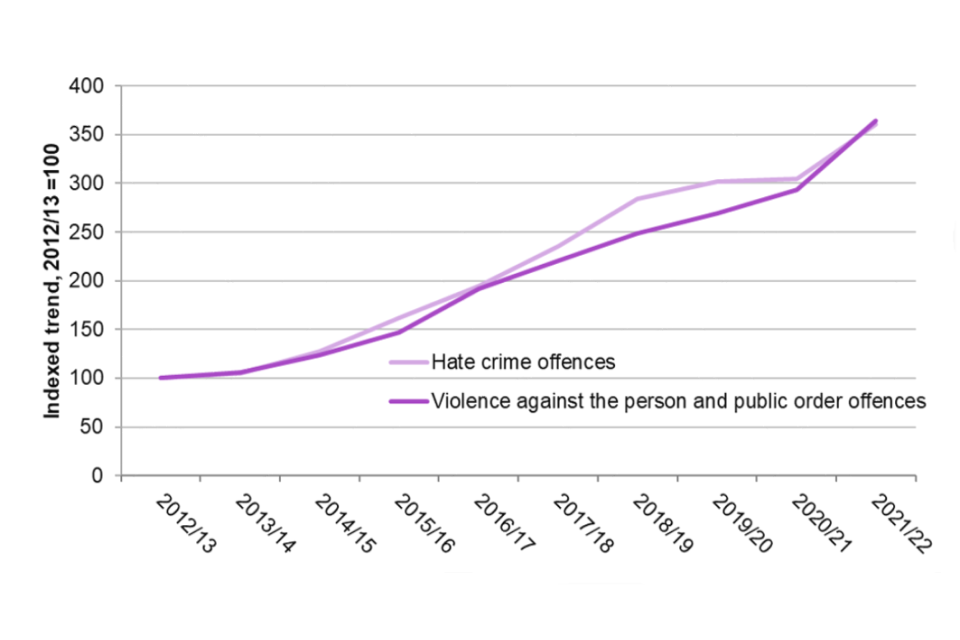

Section 2.2 shows that 92 per cent of hate crimes in year ending March 2022 were for either public order or violence against the person offences, continuing the pattern seen in previous years. These are two offence groups thought to have been previously subject to relatively high levels of under-recording and thus improvements in crime recording are likely to have had a larger impact on these groups than other offences. Figure 2.1 shows the indexed trend in overall violent and public order offences since year ending 2013 compared with all hate crime offences over the same period. As can be seen, there is a strong correlation between the increase in overall public order and violence against the person offences and hate crime. This trend has continued in year ending March 2022, suggesting that overall hate crime has increased broadly in-line with non-hate crime offences.

Figure 2.1: Indexed trends in the number of police recorded violence against the person and public order and hate crime offences, year ending March 2013 to year ending March 2022 (year ending March 2013 = 100)

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office.

Notes:

- Figures exclude GMP.

There have also been short-term genuine rises in hate crime following certain trigger events in recent years. Increases in hate crime were seen around the EU Referendum in June 2016 and the terrorist attacks in 2017. There was also an increase in public order hate crimes during the summer of 2020 following the widespread Black Lives Matter protests and far-right counter-protests.

Hate crime data by Police Force Area from year ending March 2012 to year ending March 2022 can be found in the Home Office Open Data tables.

Religious hate crimes

In April 2016, the Home Office began collecting information from the police on the perceived religion of victims of religious hate crime. By perceived, we mean the religion targeted by the offender. While in the majority of offences the perceived and actual religion of the victim will be the same, in some cases they will differ. For example, if anti-Muslim graffiti is sprayed on a religious temple of another faith, this would still be recorded as an offence of racially or religiously aggravated criminal damage and identified by the respective police force as a religious hate crime against Muslims.

There are nine different perceived religion flags in this collection, which match those reported upon in the 2021 Census:

- Buddhist

- Christian

- Hindu

- Jewish

- Muslim

- Sikh

- other

- no religion

- unknown

Of the 8,730 religious hate crimes recorded by the police in year ending March 2022, information on the targeted religion was provided in 8,307 of the offences (95%)[footnote 6].

In some cases, more than one perceived religion had been tagged on one offence (for example, a piece of graffiti may have targeted more than one religion). All police forces sent data on the perceived religion of the victims of religious hate crimes. Across all forces, in 17% of offences, the targeted religion was not known but for some forces the number of offences recorded with ‘unknown religion’ was relatively high.

In year ending March 2022, where the perceived religion of the victim was recorded, two in five (42%) of religious hate crime offences were targeted against Muslims (3,459 offences). The next most commonly targeted group were Jewish people, who were targeted in just under one in four (23%) of religious hate crimes (1,919 offences). Information on the other targeted religions for year ending March 2022 can be found in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Number and proportion of religious hate crimes recorded by the police1, by the perceived targeted religion, year ending March 2022

| Numbers and percentages | England and Wales | |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived religion of the victim | Number of offences 2021/22 | % 2021/22 |

| Buddhist | 36 | 0 |

| Christian | 701 | 8 |

| Hindu | 161 | 2 |

| Jewish | 1,919 | 23 |

| Muslim | 3,459 | 42 |

| Sikh | 301 | 4 |

| Other | 403 | 5 |

| No religion | 209 | 3 |

| Unknown | 1,426 | 17 |

| Total number of targeted religions | 8,615 | |

| Total number of offences | 8,307 |

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office.

Notes:

- In some offences more than one religion has been recorded as being targeted, therefore the sum of the proportions do not add to 100%.

- See Bulletin Table 3 for detailed footnotes.

Racial or religiously aggravated offences

The data the Home Office receives in the main police recorded crime return for racially or religiously aggravated offences are available on a monthly basis[footnote 7]. This allows analysis of in-year trends in these offences. An indexed chart of these offences and their non-aggravated equivalent offence are shown in (Figure 2.2).

There are four clear spikes in these aggravated offences which were not seen in the non-aggravated offences: July 2016, following the EU Referendum; July 2017, following the terrorist attacks seen in this year; and in Summer 2020, following the Black Lives Matter protests and far-right counter-protests following the death of George Floyd on 25th May in the United States of America. The fourth spike in the summer of 2021 was largely due to an increase of racially or religiously aggravated public fear, alarm or distress offences.

There were also spikes in July 2018 and 2019, but these follow the same trend as for the non-aggravated offences.

Figure 2.2: Indexed number of racially or religiously aggravated offences recorded by the police by month, April 2015 to March 2022

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office.

2.2 Hate crimes by type of offence

Just over half (51%) of the hate crimes recorded by the police in year ending March 2022 were for public order offences and over a third (41%) were for violence against the person offences (Figure 2.3; Appendix Table 6). Together, these offence categories accounted for just over nine in ten (92%) of all hate crimes recorded by the police in England and Wales.

Figure 2.3: Distribution of offences flagged as hate crimes, year ending March 2022

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office.

The distribution of hate crime offences differs markedly from overall police recorded crime. Theft offences accounted for just under a third (28%) of all recorded crime in year ending March 2022 (data not shown); these offences are unlikely to involve a motivating factor against a monitored strand. In contrast, public order offences accounted for just eleven per cent of all notifiable offences compared with 51 per cent of hate crime offences (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4: Breakdown of hate crimes and overall recorded crime by selected offence types, year ending March 2022

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office.

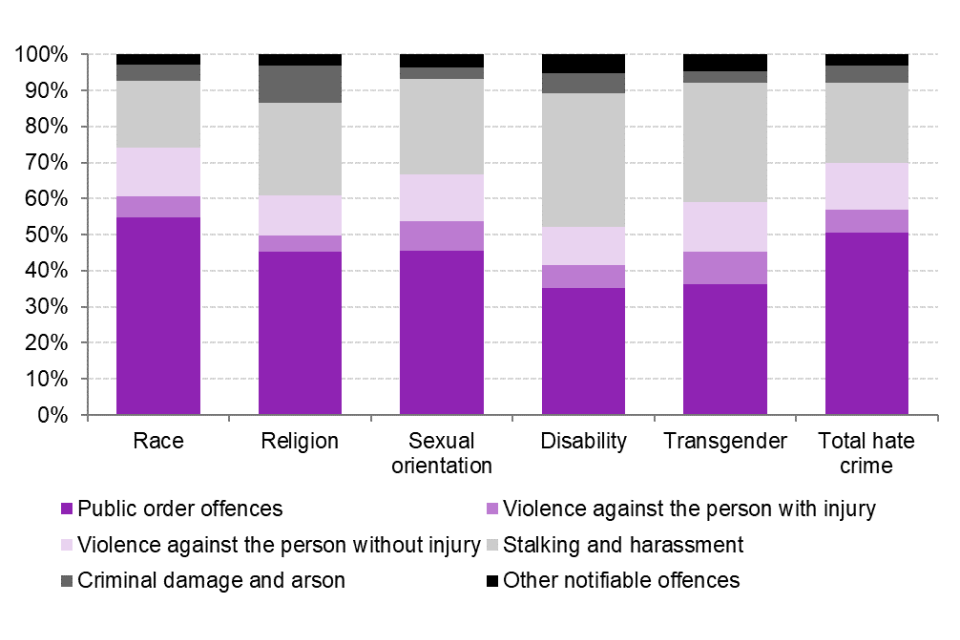

Figure 2.5 shows what type of offences were recorded for each monitored strand. As in previous years, public order offences were the most common offence to be recorded for all strands except for disability-targeted hate crime. Stalking and harassment offences were the most commonly recorded for disability-targeted hate crime offences.

Figure 2.5: Breakdown of hate crime by selected offence types and monitored strand, year ending March 2022

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office.

2.3 Hate crime outcomes

The Home Office collects information on the investigative outcomes of police recorded offences, including those that are identified as hate crimes. For further information on outcomes see Crime Outcomes in England and Wales: Year ending March 2022.

This section covers how the police have dealt with hate crimes recorded in the year ending March 2022. This analysis is based on the outcomes assigned to crimes recorded in year ending March 2022 at the time the data were extracted (June 2022) for analysis. Some offences will not have been assigned an outcome at this time and therefore these figures are subject to change.

Racially or religiously aggravated offence outcomes

Data presented in this section are for racially or religiously aggravated offences. These data were available for all police forces. Data on outcomes for all hate crime offences, which were available for 26 of the 44 police forces[footnote 8], are presented in the next section.

At the time these data were extracted, 82 per cent of racially or religiously aggravated offences had been assigned an outcome compared with 90 per cent of their non-aggravated counterparts (data not shown).

Figure 2.6 shows that racially or religiously aggravated public order and assault offences were more likely to be dealt with by a charge/summons than their non-aggravated counterparts, reflecting the more serious nature of racially or religiously aggravated offences. For example, three times the proportion of racially or religiously aggravated public fear, alarm and distress offences had been dealt with by charge/summons than the non-aggravated equivalent offences (9% and 3% respectively). In contrast, this trend was reversed for criminal damage, where non-aggravated offences were more likely to result in a charge or summons than aggravated offences (4% and 2% respectively). However, this picture may change when all investigations are complete as around fifteen per cent of criminal damage cases remained open when the analysis presented here was undertaken (data not shown).

Figure 2.6: Percentage of racially or religiously aggravated offences and their non-aggravated equivalents recorded in year ending March 2022 resulting in charge/summons, by offence type

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office.

The overall proportion of racially or religiously aggravated offences resulting in a charge and or summons was, at 8%, lower than the figure for year ending March 2021 at the time of publication last year (12%). This was driven by a 3.4 percentage point decrease in the proportion of racially or religiously aggravated public fear, alarm or distress offences being assigned a charge / summons outcome, down from 12.6% to 9.2%. This decrease has continued a previous downward trend seen since the introduction of the Outcomes Framework in year ending March 2015, when, for example, 30% of racially or religiously aggravated public fear, alarm or distress offences were resolved by a charge and or summons, in line with non-aggravated offences. As explained in the ‘Crime outcomes, England and Wales, 2021 to 2022’ statistical bulletin, the volumes of charges had been falling in recent years at the same time as volume of crimes recorded by the police has risen (with the exception of the year affected by the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions). This pattern was also observed in racially or religiously aggravated offences. There is evidence to suggest that a higher proportion of recorded crimes in recent years were for offence types which can be more challenging to investigate. This means that the investigative caseload has both grown and become more complex.

Flagged hate crime offences – Home Office Data Hub

The Home Office have implemented an improved data collection system called the Home Office Data Hub which is designed to streamline the process by which forces submit data. The Data Hub replaces the old aggregated data collection by capturing record-level crime data via direct extracts from forces’ own crime recording systems. This allows the police to provide more detailed information to the Home Office enabling a greater range of analyses to be carried out.

Using the Data Hub, it is possible to see how offences flagged as being motivated by one or more of the five monitored strands have been dealt with by the police. The analyses presented are based on data from 26[footnote 9] of the 44 police forces in England and Wales that supplied adequate data to the Data Hub; these forces data accounted for over half (54%) of all police recorded hate crime in year ending March 2022.

In total, 84 per cent of hate crime flagged offences recorded in year ending March 2022 had been assigned an outcome at the time the data were extracted from the Data Hub[footnote 10]. The remaining sixteen per cent were still under investigation. In comparison, 86 per cent of non-hate crime offences had been assigned an outcome at the time of data extraction (data not shown).

Appendix Table 4 shows that nine per cent of all hate crime flagged offences had been dealt with by a charge or summons, slightly below the published figure of ten per cent in year ending 2021. As with racially or religiously aggravated offences, the proportion of offences dealt with by charge or summons had been falling since the introduction of the Outcomes Framework.

The distribution of offences recorded by the police that constituted hate crimes were very different to overall crime. Therefore, to provide more meaningful comparisons charge/summons rates are shown below for certain offence groups.

Figure 2.4. shows that violence against the person, public order offences and criminal damage and arson offences comprised 97 per cent of hate crime flagged offences. This proportion was the same for the 26 forces included in this analysis, suggesting that these forces may be broadly representative of all.

The proportions of outcomes assigned varied by offence type (Appendix Table 5; Figure 2.7):

- seven per cent of violence against the person hate crime flagged offences, and five per cent of criminal damage and arson hate crime flagged offences, were dealt with by a charge or summons, similar proportions to non-flagged offences (6% and 4% respectively)

- a greater proportion (10%) of hate crime flagged public order offences had been dealt with by a charge or summons compared with non-hate crime flagged public order offences (6%)

Figure 2.7: Percentage of selected offences dealt with by a charge/summons, offences recorded in year ending March 2022, 26 forces

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office Data Hub.

The most frequent outcome recorded for violent offences was “evidential difficulties as the victim does not support action”; this was the outcome for 30 per cent of hate crime flagged violence against the person offences compared with 41 per cent of non-hate crime flagged offences (Appendix Table 5).

Figure 2.8 shows the proportion of hate crimes that were dealt with by charge or summons for each of the five hate crime strands for three offence groups. While the proportions for race, religious and sexual orientation hate crimes tended to be higher than for non-hate crimes, the figures for disability and transgender hate crime were lower.

Figure 2.8: Percentage of selected offences resulting in charge/summons, by hate crime strand, offences recorded in year ending March 2022, 26 forces

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office Data Hub.

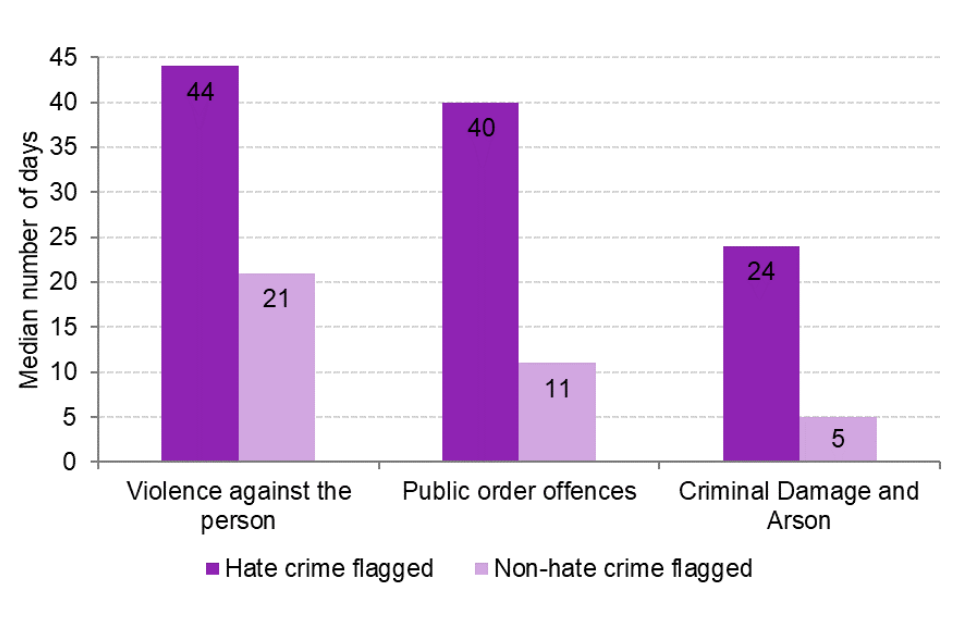

Figure 2.9 shows the median number of days taken to assign an outcome, from the date the crime was recorded, for selected hate crime and non-hate crime offences. Hate crime offences, on average, took longer to be assigned a final outcome than non-hate crime offences. For example, the median number of days taken to assign an outcome to criminal damage and arson hate crime offences was 24 days, compared with five days for non-hate crime offences. Similarly, it took longer to assign an outcome to violence against the person hate crime offences (median=44 days) than to non-hate crime flagged violent offences (median=21 days). This suggests more investigative effort being devoted to hate crime offences which reflects the more serious nature of these crimes.

Figure 2.9: Median number of days taken to assign an outcome, hate crime flagged and non-hate crime flagged offences, outcomes recorded in year ending March 2022, 26 forces

Source: Police recorded crime, Home Office Data Hub.

Experimental Statistics: Ethnicity of victims in racially or religiously aggravated crimes – Home Office Data Hub

From April 2021, it became a requirement for forces to provide the Home Office with the ethnicity of victims of racially or religiously aggravated offences. As this is the first year that the collection has been mandatory, these data are published as experimental Statistics. Experimental statistics are official statistics that are in the testing phase and not yet fully developed. Users should be aware that experimental statistics will potentially have a wider degree of uncertainty. Home Office Statisticians will continue to monitor the quality of these data in the future and will work with police forces to improve data quality. Data for 38 of the 44 police forces[footnote 11], are presented in the next section. These 38 forces represented 94 per cent of racially or religiously aggravated crimes in year ending March 2022.

Of the 71,602 racially or religiously aggravated crimes recorded by the police in year ending March 2022, information on the victim ethnicity was provided in 41,441 of the offences (58%).

In year ending March 2022, where the ethnicity of the victim was known, the victim was identified by the police as being White in around a third of offences (33%). Just under a third of victims were identified as Black (30%) or Asian (also 30%; Table 2.3). Accounting for different population sizes shows that Black and Asian people had higher rates of victimisation. In year ending March 2022, based on the published population figures by ethnicity from 2011[footnote 12], Black victims had a rate of 33.8 aggravated offences per million population, compared with 16.8 per million population for Asian victims and 1.5 per million population for White victims (data not shown).

These population data by ethnicity are now several years out of date. These figures will be updated when figures from the 2021 Census are published later this year.

Data should be treated with caution due to the relatively high proportion of offences where the ethnicity of the victim has not been identified by forces. Lastly, among the White victims may be people not born in the UK who have suffered xenophobic abuse.

Table 2.3: Proportion of racially or religiously aggravated offences recorded by the police, by victim ethnicity (where known), year ending March 2022

| Percentages | England and Wales | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Offence Code | Description | White | Black | Asian | Middle Eastern | Chinese, Japanese or South Asian |

| 105B | Racially or religiously aggravated assault without injury | 28 | 34 | 30 | 5 | 3 |

| 58J | Racially or religiously aggravated criminal damage | 38 | 24 | 31 | 4 | 3 |

| 8M | Racially or religiously aggravated harassment | 38 | 27 | 28 | 4 | 2 |

| 8P | Racially or religiously aggravated assault with injury | 31 | 29 | 31 | 6 | 3 |

| 9B | Racially or religiously aggravated public fear, alarm or distress | 34 | 30 | 30 | 4 | 3 |

| Total | 33 | 30 | 30 | 4 | 3 |

3. Police recorded hate crime data sources and quality

3.1 Introduction

In January 2014, the UK Statistics Authority published its assessment of ONS crime statistics. It found that statistics based on police recorded crime data, having been assessed against the Code of Practice for Official Statistics (now the Code of Practice for Statistics), did not meet the required standard for designation as National Statistics.

Police forces have made significant improvements in how they record crime since 2014. They have also improved their identification of what constitutes a hate crime over this time period. Because of these changes, police recorded crime figures do not currently provide reliable trends in hate crime. The figures do, however, provide a good measure of the hate crime-related demand on the police.

The UK Statistics Authority published a list of requirements for these statistics to regain the National Statistics accreditation. Some of the requirements of this assessment were to provide more detail on how data sources were used to produce these statistics, along with more information on the quality of the statistics. Additionally, there was a requirement to provide information on the process used by police forces to submit and revise data, and the validation processes used by the Home Office. To ensure that this publication meets the high standards required by the UK Statistics Authority, details are provided below.

In May 2022, the Office for Statistics Regulation (OSR) wrote to the Home Office following their compliance review into published hate crime statistics across the UK[footnote 13]. The OSR recognised the difficulties in measuring hate crime but found a range of positive features that demonstrate the value and quality of the published statistics in their review. Additionally, they recognised the difficulty in presenting data on police recorded hate crime without the CSEW estimates to provide context to the numbers, meaning “it is difficult to determine whether police recorded hate crime is increasing”. They stated that they had heard from users of a ‘perception problem’, where “the public is likely to see police recorded crime as the main data source, despite ongoing concerns about data quality” and asked the Home Office to make clear in this publication the limitations of police recorded crime data. We have added on the uncertainty of police recorded crime trends to the bulletin in response to this recommendation.

3.2 Police recorded crime data sources and validation process

Hate crime data are supplied to the Home Office by the 43 territorial police forces of England and Wales, plus the British Transport Police. Greater Manchester Police have not been unable to supply data for year ending March 2020 following the implementation of a new IT system in July 2019.

Forces either supply the data at least monthly via the Home Office Data Hub (HODH) or on an annual basis in a manual return. For forces with data on the Data Hub, the Home Office extracts the number of offences for each force which have been flagged by forces as having been motivated by one or more of the monitored strands. Therefore, counts of hate crime via the HODH are dependent on the flag being used for each hate crime offence. It is then possible to derive the count of offences and the monitored strands covered.

In the manual return, police forces submit both the total number of hate crime offences (that is a count of the number of unique offences motivated by one or more of the five monitored strands) and the monitored strands (or motivating factors) associated with these offences. From year ending March 2016, police forces who returned data manually were required to provide an offence group breakdown for recorded hate crimes; prior to year ending March 2016 only an aggregated total of hate crimes for each of the five strands was asked for. It is possible for more than one of the monitored strands (motivating factors) to be assigned to a crime. For example, an offence could be motivated by hostility to race and religion, so would be counted under both strands but would only constitute one offence.

It is known that for some police forces, the addition of tags to crime records could be improved. For example, there may be crimes that are operationally treated as a hate crime but were not correctly identified as a hate crime on their crime recording system. In July 2018, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS) published a report on how the police deal with hate crime, including how crimes are flagged. Findings included a lack of recognition in forces about how important the flagging of hate crimes is and concerns around the lack of effective audit arrangements to check flags had been applied correctly.

The full report can be found here: Understanding the difference: the initial police response to hate crime.

In July 2021 the Government announced plans to publish an updated hate crime strategy this year. The strategy will outline plans on how the Government will work with the police and other law enforcement agencies to deliver improvements in the police response to hate crime.

Further information on how the police record hate crime can be found in the College of Policing’s Authorised Professional Practice guidance on hate crime publication launched in October 2020.

At the end of each financial year, the Home Office carry out a series of quality assurance checks on the hate crime data collected from the police forces (either by aggregate return or via the HODH).

These checks include:

- looking for any large or unusual changes in hate crimes from the previous year

- looking for outliers

- checking that the number of hate crimes by strand is higher than the total number of offences; where these two figures were the same, the force was asked to confirm they were recording multiple hate crime strands

Police forces are then asked to investigate these trends and either provide an explanation or resubmit figures where the reconciliation identifies data quality issues.

The data are then tabulated by monitored strand and year and sent back to forces for them to verify. At this stage, they are asked to confirm in writing that the data they submitted are correct and if they are not, then they have the opportunity to revise their figures.

From April 2016, the Home Office began collecting information from the police on the perceived religion of victims of religious hate crimes – that the religion targeted by the offender. While in the majority of offences the perceived and actual religion of the victim will be the same, in some cases this will differ. For example, if anti-Muslim graffiti is sprayed on a religious temple of another faith, this would be recorded as an offence of racially or religiously aggravated criminal damage and flagged by the respective police force as a religious hate crime against Muslims. This collection was voluntary in year ending March 2017 and made mandatory for year ending March 2018.

From April 2021, the Home Office has begun the collecting the ethnicity of the victims of racial hate crimes recorded by the police. These were published for the first time as Experimental Statistics in this statistical bulletin.

3.3 Understanding differences between the CSEW and police recorded hate crime

Statistics on police recorded hate crime are published on an annual basis, with estimates from the CSEW published every third year. However, due to the suspension of the face-to-face CSEW due to public health restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, the next estimates from the CSEW will be delayed.

Trends in police recorded and CSEW hate crime have been notably different over recent years. Police recorded hate crime has risen, while the CSEW has shown a fall over the longer-term. The main reason for this difference will be due to the improvements to recording processes and practices made by the police since 2014. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS) have conducted a range of inspections related to police forces’ crime and incident recording practices in recent years. In 2014, Crime recording: making the victim count concluded that 33% of cases involving violence were not recorded by the police in England and Wales. Improvements made by the police were identified in their report State of policing: 2019 where a lower proportion (12%) of violent offences reported to the police went unrecorded.

These improvements have made substantial contributions to rises in recorded crime over recent years. This effect has been more pronounced for some crime types, such as violence against the person and public order offences. These offences account for 9 in 10 police recorded hate crimes, meaning police figures do not currently provide reliable trends in hate crime. The absence of CSEW estimates means it is harder to determine with increased in police recorded hate crime are genuine, or a continuation of recording improvements.

Additionally, there are a number of differences in the coverage of the CSEW and police recorded crime.

The CSEW is a victimisation survey which covers adults aged 16 and over resident in households in England and Wales. Police recorded crime figures includes crimes against people of all ages, against society (crimes where there is not a direct victim such as public order offences) as well as businesses and institutions. This is a key difference for hate crime offences as public order offences are not well covered by the CSEW, as many of these offences will not involve a specifically identifiable victim. Conversely, public order offences account for over a half of police recorded hate crime.

The sources cover different time periods. The most recently available CSEW data were for the combined three annual datasets – year ending March 2018, year ending March 2019 and year ending March 2020. Furthermore, as respondents are interviewed throughout the survey year for their experiences of crime in the year to interview, the three-year survey period actually relate to a near four-year period. This is required to produce more robust estimates on numbers of hate crimes per year from the survey. The CSEW will therefore only give a very broad estimate of the level of hate crime in England and Wales across these four years and will not provide any information on whether the level of hate crime has changed in this period.

Police recorded hate crime data are available on an annual basis. In addition, for racially or religiously aggravated offences, data are available for all police forces in England and Wales on a monthly basis so trends in these crimes around events such as the EU Referendum and the terrorist attacks in 2017 can be examined. However, as mentioned above it is known that police recorded crime data have been heavily affected by improvements in crime recording by the police over recent years, so data from the police are limited in assessing longer-term trends in hate crime.

Other differences in coverage include:

- respondents to the CSEW might misunderstand the survey questions; when they are asked whether they think a crime was committed because of a motivating factor, they may instead be responding based upon their perceived vulnerability; this is likely to be a reason why the estimate of disability hate crime is much higher in the CSEW than the number of these offences recorded by the police

- the respondent is asked in the survey whether the hate crime incident came to the attention of the police and, not whether the police actually recorded a crime (the police may witness an incident and decide that a crime was not committed, for example)

- similarly, while a respondent might say the crime did come to the attention of the police, the survey does not ask whether the respondent told the police that they thought it was motivated by one of the five hate crime strands; it is possible that some offences estimated by the survey may have been recorded by the police as a crime, but not specifically as a hate crime

- in the recording of a crime, it might not become apparent that there was a motivating hate factor, meaning that police may not ask the direct question whether the victim thought that the crime was a hate crime.

Source: https://www.gov.uk/

Join us in helping to bring reality and decency back by SUBSCRIBING to our Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQ1Ll1ylCg8U19AhNl-NoTg and SUPPORTING US where you can: Award Winning Independent Citizen Media Needs Your Help. PLEASE SUPPORT US FOR JUST £2 A MONTH https://dorseteye.com/donate/