Right-wing political parties across many Western democracies, including the UK, the US, and Australia, have long-standing and well-documented financial ties to the fossil fuel lobby. These relationships are sustained through substantial donations from major oil, gas, and coal companies, as well as from influential individuals with vested interests in maintaining the status quo of fossil fuel dependency. In exchange, these parties often champion policies that favour deregulation of environmental protections, delay climate action, and prioritise economic growth over ecological sustainability. This mutually beneficial dynamic ensures that the fossil fuel industry retains political influence, while right-wing parties secure the financial backing necessary for election campaigns and party infrastructure.

The fossil fuel lobby’s support goes beyond direct funding, encompassing sophisticated networks of think tanks, lobbying firms, and media outlets that propagate climate scepticism and downplay the urgency of transitioning to renewable energy. These entities often align ideologically with right-wing values, promoting free-market fundamentalism and opposition to what they term as “green overreach” or excessive government intervention. As a result, right-wing parties frequently adopt positions that are either hostile to or dismissive of climate science, framing climate policies as economically damaging or anti-business. This narrative is carefully cultivated to undermine public support for climate action while legitimising continued fossil fuel exploitation.

In the UK, for instance, the Conservative Party and Reform UK have received significant donations from individuals and organisations linked to the fossil fuel sector. This funding often correlates with political resistance to robust climate legislation, such as delays in implementing net-zero targets or support for new oil and gas exploration licences in the North Sea. The alignment of political and corporate interests serves to entrench fossil fuel dependency, even as scientific consensus and international pressure mount for decisive climate action. Such entanglements highlight the broader systemic challenge of achieving climate goals within political systems heavily influenced by powerful, carbon-intensive industries. A lot of this money is also spent on spreading climate denial lies across the media.

As record-breaking heatwaves, wildfires, and floods dominate headlines, it’s easy to assume public awareness of climate change is a recent phenomenon. But the story of how we came to understand this crisis stretches back centuries, and it wasn’t scientists alone who sounded the alarm. From Victorian-era discoveries to protest songs of the 1970s, and from obscure newspaper clippings to viral Greta Thunberg speeches set to music, media and musicians have played a crucial, often overlooked role in pushing climate change into public consciousness.

This is the untold story of how journalism and art have framed, and sometimes failed, the defining issue of our time.

The Lost Warnings (1800s–1950s): When Science Spoke, But No One Listened

Long before “climate change” entered our vocabulary, the foundations were being laid and ignored. In 1856, scientist Eunice Newton Foote demonstrated that carbon dioxide trapped heat, suggesting that rising CO₂ levels could warm the planet. Her findings were presented at a major scientific conference… and then forgotten.

By 1896, Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius calculated that burning fossil fuels might eventually overheat the Earth. But with industrialisation in full swing, his warnings were dismissed as speculative. The media? Almost entirely silent.

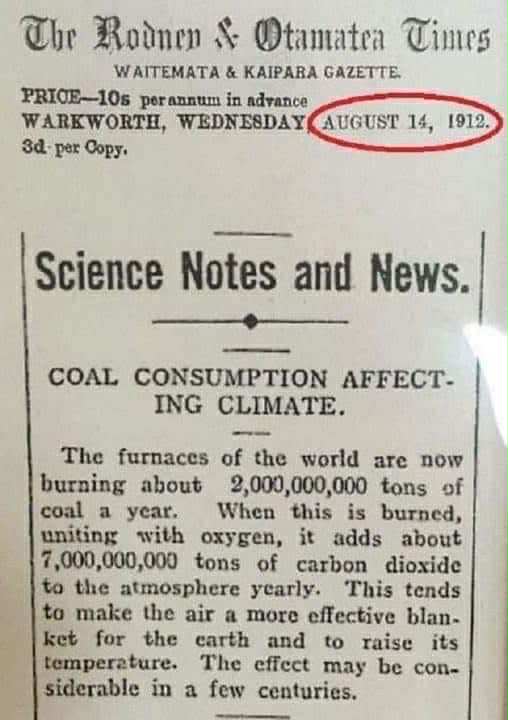

When climate science did appear in early 20th-century press, it was often buried in back pages or framed as curious speculation rather than a looming disaster. A 1912 article in Popular Mechanics briefly noted that coal burning might alter the climate, but it was treated as a distant hypothetical, not a coming crisis.

Why did these early warnings fail?

- Media prioritised industrial progress over its consequences

- Climate science was complex and “unsexy” for newspapers

- The fossil fuel industry wasn’t yet powerful enough to suppress dissent

Yet in hindsight, the signs were there—just waiting for artists and journalists to amplify them.

The 1960s–70s: Counterculture Awakens the Climate Movement

The environmental movement as we know it began not with scientists, but with Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), which exposed pesticide dangers and proved the media could spark mass ecological awareness.

By the late 1960s, something shifted. NASA’s Earthrise photo (1968) gave humanity its first full view of the planet—a fragile blue marble in space. The image became a cultural lightning rod, appearing everywhere from newspaper front pages to album covers, forcing a reckoning: What are we doing to our only home?

Music’s First Climate Protest Songs

While most early environmental music focused on pollution, some artists tapped into deeper anxieties about ecological collapse:

- The Doors – “Ship of Fools” (1970)

Jim Morrison’s haunting lyrics painted a dystopia where humanity sails blindly toward ruin: “The human race was dyin’ out / No one left to scream and shout.”

A metaphor for climate denial before the term existed. - Joni Mitchell – “Big Yellow Taxi” (1970)

Her lament for paved-over nature became an accidental environmental anthem: “They took all the trees, put ’em in a tree museum / And charged the people a dollar and a half just to see ’em.” - Marvin Gaye – “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)” (1971)

One of the first mainstream soul songs to confront environmental ruin: Oil wasted on the ocean and upon our seas / Fish full of mercury.”

Meanwhile, media coverage remained patchy. While The New York Times and The Guardian ran occasional climate stories, most outlets treated it as a fringe concern. In 1975, Newsweek even declared a coming ice age—a misreporting that fossil fuel interests would later exploit to sow doubt.

1980s–90s: The Media Battlefield—Science vs. Skepticism

Everything changed in 1988, when NASA scientist James Hansen testified to Congress that global warming had begun. Suddenly, climate was front-page news. TIME magazine declared “Endangered Earth” its Planet of the Year, and the IPCC was formed to assess the science.

But a backlash was brewing. Fossil fuel companies, following Big Tobacco’s playbook, funded climate denial campaigns—and found willing partners in conservative media.

Key Media Failures:

- False balance: Outlets like the BBC gave “equal weight” to climate deniers long after scientific consensus was clear

- Corporate censorship: Investigative reports on oil companies were often spiked

- Disaster framing: Climate stories focused on polar bears, not people, making the crisis feel distant

Music Fights Back

As corporate media waffled, musicians got more confrontational:

- Midnight Oil – “Beds Are Burning” (1987)

A protest anthem demanding justice for Indigenous land—and by extension, the planet. - Radiohead – “Paranoid Android” (1997)

Thom Yorke’s lyrics skewered consumerism’s role in ecological decay: “The dust and the screaming / The yuppies networking.”

Yet for all this, most 90s climate coverage was reactive—focused on summits and treaties, not systemic change.

2000s–2010s: From Alarm to Action

The 2000s saw climate journalism mature—and music become overtly activist.

Media Breakthroughs:

- 2006: Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth forced climate into multiplexes

- 2009: “Climategate” showed how easily misinformation could derail coverage

- 2018: The Guardian dropped “climate change” for “climate crisis”—a linguistic shift that mattered

Music’s Radical Turn:

- The 1975 – “The 1975” (2019)

The band handed their intro track to Greta Thunberg, whose speech became a generational rallying cry: “We have to acknowledge that the older generations have failed.” - Billie Eilish – “All the Good Girls Go to Hell” (2019)

Her music video depicted California in flames—a direct link between art and climate emergency.

2020s: The Reckoning

Today, climate coverage is ubiquitous but uneven. While The Guardian and BBC report aggressively, right-wing outlets still peddle delayism. Meanwhile, musicians like Little Simz and Kendrick Lamar weave climate justice into their lyrics.

The lesson? Media and music don’t just report on climate change—they shape how we feel about it. From Morrison’s “Ship of Fools” to Thunberg’s viral speeches, artists and journalists have been our canaries in the coal mine. The question is: Are we finally listening?