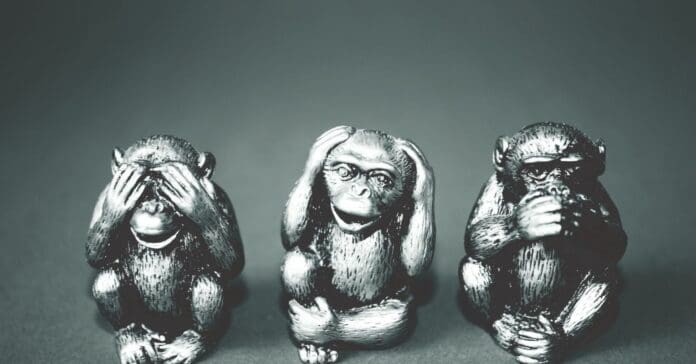

White Innocence and Racial Denial: Blindness, Deafness, and the Refusal of Responsibility

James Baldwin’s work remains one of the most incisive analyses of white denial in modern racial orders. Although writing primarily about the United States, Baldwin’s insights translate powerfully to Britain, where racism is frequently disavowed as either imported, historical, or exceptional rather than structural and ongoing. This article argues that many white Britons remain both blind and deaf to the lived realities of non-white people, not due to ignorance alone, but because racial innocence functions as a psychological and political defence of power.

White Innocence and the Myth of Neutrality

Baldwin famously wrote that “It is the innocence which constitutes the crime” (The Price of the Ticket, 1985). This innocence is not a lack of knowledge but a refusal to know. In the British context, it manifests through the persistent framing of empire, slavery, and colonial violence as unfortunate but peripheral episodes, disconnected from present inequalities. As Paul Gilroy argues, Britain suffers from a “postcolonial melancholia” in which imperial history is neither fully mourned nor meaningfully confronted, leading to nostalgia rather than accountability.

White British identity is often imagined as culturally neutral, with racialised identities positioned as deviations from an unmarked norm. Stuart Hall observed that whiteness in Britain operates precisely through its invisibility: “Race is only noticed when it is the race of the Other.” This renders whiteness exempt from scrutiny while non-white populations are continually problematised, measured, and explained.

Deafness to Non-White Testimony

A central feature of racial domination is not merely the silencing of marginalised voices, but the systematic disbelief of those voices when they are heard. Baldwin noted that “People who shut their eyes to reality simply invite their own destruction” (No Name in the Street, 1972). In Britain, non-white testimonies of racism—particularly regarding policing, immigration enforcement, and employment discrimination—are routinely met with scepticism or accusations of exaggeration.

Audre Lorde’s observation that “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” is instructive here. Non-white individuals are often expected to articulate their experiences using frameworks deemed acceptable by white institutions, while emotional expression or anger is dismissed as irrational. The demand for constant proof places the burden of racism on those who experience it, rather than on the structures that produce it.

Frantz Fanon described this dynamic in Black Skin, White Masks as a colonial condition in which the oppressed are forced to “justify their existence” to a dominant group that assumes its own universality. In contemporary Britain, this persists in debates about immigration, national belonging, and “integration,” where non-white people are asked to demonstrate loyalty to a nation that continues to marginalise them.

The Privilege of Ignorance

W.E.B. Du Bois’s concept of “double consciousness” remains central to understanding racial asymmetry. He described it as “this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others.” Non-white Britons must navigate both their own self-understanding and the expectations of a society structured by whiteness. White people, by contrast, are rarely required to understand themselves through non-white perspectives.

This asymmetry constitutes what might be termed the privilege of ignorance. White Britons can choose whether or not to engage with racism, often encountering it only as an abstract moral issue rather than a lived reality. Education systems that downplay empire, media that centre white perspectives, and political rhetoric that treats racial inequality as a niche concern all reinforce this privilege.

As Sara Ahmed argues, declarations of equality often function as barriers to change: “When equality becomes a description of what we already have, it becomes harder to notice inequality.” Britain’s self-image as tolerant and multicultural frequently operates in this way, obscuring enduring racial hierarchies beneath celebratory narratives of diversity.

Resistance to Structural Accountability

Baldwin warned that acknowledging racial injustice would require white societies to confront uncomfortable truths about their foundations. “If one really wishes to know how justice is administered in a country,” he wrote, “one does not question the policemen, the lawyers, the judges… one observes the treatment of those whom the society regards as its dregs.”

In Britain, racial inequality is frequently individualised—reduced to questions of attitude or behaviour—rather than understood as systemic. This allows institutions to disavow responsibility while continuing practices that disproportionately harm non-white communities, from stop-and-search policing to hostile environment immigration policies.

Stuart Hall cautioned that racism does not disappear but adapts, becoming “coded into everyday language and common sense.” Contemporary British racism often presents itself as pragmatic, bureaucratic, or concerned with “fairness,” while reproducing exclusion through ostensibly neutral procedures.

In summary, white blindness and deafness to racial oppression in Britain should not be understood as accidental failures of perception but as active strategies of denial that protect historical and contemporary power. As Baldwin insisted, “History is not the past. It is the present.” To refuse to see non-white suffering is to refuse responsibility for the conditions that produce it.

The challenge Baldwin posed remains unresolved: whether white societies will continue to cling to comforting myths of innocence, or whether they will accept the far more demanding task of truth. Seeing clearly is not a matter of goodwill but of justice—and justice, as Baldwin reminds us, always carries a cost.