Law Enforcers Against Prohibition (LEAP UK) are launching their campaign for a sensible approach to drug policy at the House of Commons on the 29th February. One of the attendees will be a retired magistrate who lives in Dorchester – he will discuss his own views for Dorset Eye when I cover the event.

LEAP has run a long and successful campaign in the US and unlike many pro drugs campaign organisations is extremely well organised, as a bunch of police, spies and judges would be! A few years ago they leaked me a Snowden story about how the NSA was illegally using wiretap information against its own citizens by feeding information to the Drug Enforcement Agency who in turn used high grade spy information to bust bottom rung drug dealers – this was against US law in its own right.

The law enforcers have come to their views after many years of fruitlessly throwing dealers and their clients in prison, only for them to come back out and re-offend.

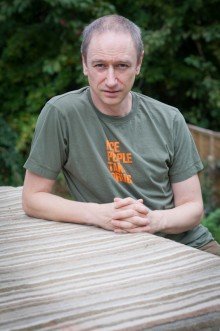

I interviewed Neil Woods, an ex undercover cop who spent many years infiltrating drugs gangs. What follows is a verbatim account that shows how he came to his own conclusions.

“I served 23 years in the police, 14 of those undercover. It wasn’t all of the time – I worked six months on, six months off. It was almost exclusively against drugs gangs, though some of the work I did was over stolen cars and other things but they were generally part of drugs operations anyway. I don’t think I ever went up against cannabis operations, it was mostly heroin and crack. What I was trying to do was most of the time I was trying to infiltrate drugs gangs from the bottom up to catch middle management gangsters mostly – the people who would run the regional supply of heroin and crack cocaine in city centres mostly.”

“I went into the police, believing like a lot of people do really, that if you’ve become addicted to drugs then that’s because you’ve made the daft mistake of trying them and if you haven’t got the willpower to get out of it then that’s your failing. It’s a harsh view but I think that it’s a view that a lot of people have. In trying to infiltrate these gangs I would spend a lot of time with problematic drug users. I realised that these people needed a lot of help. It was the nature of my work that I manipulated these people. It became important for people to introduce me to gangsters. I would be manipulating people and literally putting them in more danger. Me being the instrument of the State I came to realise that the resources that were put into my time would be better used actually helping these people. It finally dawned on me that I was significantly part of the problem.”

“Over the years that I worked undercover the organised crime gangs got nastier. One job I was persuaded to do in Northampton was because the gangsters there were using rape as punishment. This was the increasing levels of nastiness that was happening. Eventually it dawned on me that it was caused by police officers like me. We had to develop our tactics to be more sly and wily to infiltrate those groups and they got wise to tactics. They therefore create countermeasures. The most effective countermeasure that organised crime has is the increased use of fear and intimidation. If you can intimidate an entire community into not speaking to the police and intimidate that entire community to make the life of undercover police really difficult, then that’s your best defence. The increasing specialism and development of police tactics that I helped develop (I was involved in the training as well) the immediate effect is that it made our communities less safe.”

“With absolute certainty that I had no impact at all, either by undercover or street policing, on the supply of drugs. The most impact I have had was on a city centre for about two hours. It never had any impact on the price, it never stopped flowing at all, and I can safely say that through the work I did was make the lives of the vulnerable less bearable.”

“I came to this conclusion right at the end of my career. I knew that the war on drugs was a failure, I knew it couldn’t be won, but from a policing point of view where I had the skills and opportunity to catch some of these nasty gangsters who did all these nasty things, then I was always going to take that option. It really only occurred to me the extent of the harms that I was causing right at the end.”

“I’m hoping that these observations I’ve made can help people through these simple truths a lot quicker than it dawned on me really!”

The fact that his work was actually causing the harm that he was trying to fight dawned on him gently rather than a ‘Road to Damascus’ moment. “I had to take some amphetamine on the job in a pub because I’d made a bit of a daft mistake and set myself up as a bit of a connoisseur of amphetamine and to save myself some injury I had to really be seen to be taking this so, after having been awake for three nights I realise that I needed to know more about that commodity in order to navigate this world and so I set out to learn as much as I possibly could about drugs. That journey of trying to understand took me to the conclusions that I came to.”

“One of the first paths to that journey was that I went to a Narcotics Anonymous European open meeting in about 1999. They were proposing at that meeting that NA lobby government to allow drug offenders to be sentenced to go to NA rather than receive a prison sentence. Considering that was before Portugal went on to decriminalise that was pretty forward thinking in a way. I asked a really stupid question, ‘Well surely that’s not going to be of any help? People are only going to get the help when they want it themselves? This is quite an orthodox view. The people on the panel looked at each other and the audience went quiet – you could almost see the Tumbleweed! A member of the panel said, ‘Do you think there’s a single one of us here who haven’t been dragged, kicking and screaming to get some help?’ I looked around and everyone was shaking their heads like, it actually took someone from outside that bubble to care and to look out for them and do something for them. That was quite a moment! That puts the onus of responsibility on other people doesn’t it? As a representative of the State that throws the ball right back at me doesn’t it?”

“From that point onwards when I was moving among problematic drugs users, whose basic existence was finding the next money for a fix it sort of becomes obvious that in order to take them out of that situation, in order to protect them from gangsters manipulating them, to protect them from sexual exploitation and having to commit crime, a very simple thing to do would be to provide them with heroin. Once that person is safe, then they can be presented with the question, ‘what do you want to do about it?’ It should start from the position of the State to ensure that everyone is safe. National statistics show that heroin deaths have gone up by 2/3rds in two years. There are 50 people dying a week due to drug overdoses – now I call that a social disaster! Virtually every single one of those deaths is preventable.”

“When I was working in conventional policing (I was in CID as a Detective Sergeant) because I was heavily involved in drugs, I was involved in the investigation into drug deaths a lot more than I would want to really because it was very difficult to know what to say to the parent of a drug death. It’s the worst job in the police really. I can say that every single one of those deaths could have been prevented with a regulated system if prohibition didn’t exist. We could guarantee safety, we could have proper healthcare… – regulation solves all the problems. It really does!”

“Anyone with an addition needs a stable environment to tackle that addiction. The illicit drug market is not a stable environment. An illicit drug market is always going to compound problems. We can take away those problems by taking away the illicit nature of that market. The UN report published last autumn concluded that the level of punitive measures have little or no impact on drug use. I can absolutely evidence that myself from working undercover. The law in this country has no impact on people’s drug taking decisions at all. Why on earth are we spending billions policing it?”

“I have been campaigning for about 18 months. I left the Force in 2012 but didn’t join Law Enforcers Against Prohibition until 2014. I am a member of LEAP but looking around, to my mind the most important drugs campaign of all is Anyone’s Child because it can be such an abstract thing to convince people of drug reform. The reason I changed my mind is because of empathy. This is the key thing to people understanding this topic because it’s not an abstract issue. This about people dying and families suffering. The system doesn’t work and is causing that suffering. The Anyone’s Child campaign is about getting the general public to understand the issue and to sit up and take notice and so I will be supporting it as much as I possibly can.”

“The Bristol Anyone’s Child event was quite interesting. It is quite a liberal city. I actually get tired of talking to people who are already converted. It is very hard to find an audience who don’t know it already. We found this in Bristol. It was almost entirely a naïve audience. They were asking questions from the point of view of people who really didn’t understand, so it went down positively. People listened, they were convinced. It just goes to show that the Anyone’s Child campaign can attract people who aren’t already reformers. It was also a surprisingly young audience who were pretty naïve about the topic – that was great!”

“Anyone’s Child will be doing a national tour and we will be asking for people’s help in organising it. We can’t rely on social media to reach the right audience. We need to leaflet drop. If anyone has got a venue in mind, or if someone has a family interest please look us up.”

“LEAP has our official launch on February 29th– Leap Year Day – where the Executive Director of LEAP in the United States, and people from Belgium and Germany will be there too because we’re an international organisation.”

Neil Woods has written a memoir called Good Cop Bad War that will be published in June 2016.

Richard Shrubb