The forests still burn, but the world now looks away. In both the Amazon basin and the rainforests of Indonesia, the world-scorching inferno rages on, already forgotten by most of the media. Intricate living systems, species that took millions of years to evolve, are being incinerated in moments, then replaced with monocultures. Giant plumes of carbon tip us further into climate breakdown. And we’re not even talking about it.

But underneath the grief and frustration, I also feel disquiet. We rightly call on other nations to protect their stunning places. But where are our rainforests? I mean this both metaphorically and literally. Out of 218 nations, the UK ranks 189th for the intactness of its living systems. Having trashed our own wildlife, our excessive demand for meat, animal feed, timber, minerals and fossil fuels helps lay waste to the rest of the world.

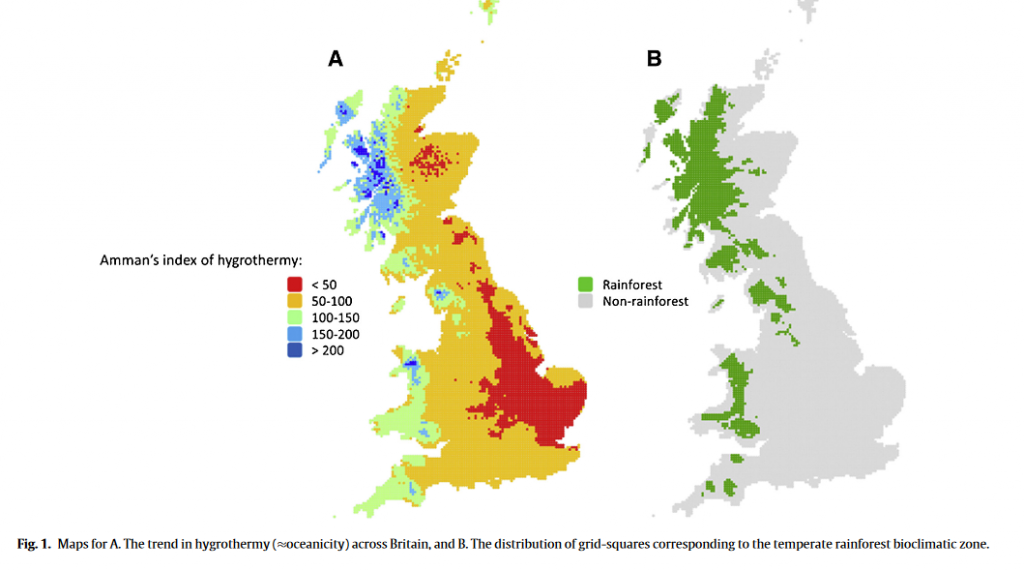

Among our missing ecosystems are rainforests. Rainforests are not confined to the tropics: a good definition is forest wet enough to support epiphytes: plants that grow on other plants. Particularly in the west of Britain, where tiny fragments persist, you can find trees covered in rich growths of a fern called Polypody, mosses and lichens, and flowering plants climbing the lower trunks. Learning that Britain is a rainforest nation astounds us only because we have so little left.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1470160X16303016

We now know that natural climate solutions – using the mass restoration of nature to draw down carbon from the air – offer, alongside keeping fossil fuels in the ground, perhaps the last remaining chance to prevent more than 1.5°, or even 2°, of global heating. Saving the remaining rainforests and other rich ecosystems, while restoring those we have lost, is not just a nice idea: our lives may depend on it. But in countries like the UK, we urge others to act, while overlooking our own disasters.

Foreigners I meet are often flabbergasted by the state of our national parks. They see the sheepwrecked deserts and grousetrashed moors and ask “what are you protecting here?”. In the name of “cultural heritage” we allow harsh commercial interests, embedded in the modern economy but dependent on public money, to complete the kind of ecological cleansing we lament in the Amazon. Sheep ranching has done for our rainforests what cattle ranching is doing to Brazil’s. Then we glorify these monocultures – the scoured, treeless hills – as “wild” and “unspoilt”.

When the International Union for Conservation of Nature sought to classify our national parks, it had to invent a new category. Most of the world’s national parks are Category I or II: set aside principally for nature. But all of ours are Category V: places where, in practice, business comes first and nature last. Much of the land in our national parks is systematically burnt. In the northern parks, this destruction is wreaked by grouse estates, and in Snowdonia by farmers. But on Dartmoor and Exmoor, the park authorities do it themselves, torching wildlife, roasting the soil, pouring carbon into the skies: everything we condemn elsewhere.

The government’s new Landscapes Review is better than I expected, but its positive proposals are in no way commensurate with our ecological and climate crises. It suggests that England’s national parks and other protected landscapes should “have a renewed mission to recover and enhance nature … simply sustaining what we have is not nearly good enough.” But it does not argue that any of our parks should aim for something better than Category V. Nor does it recommend that burning should cease, or that farming should withdraw from some places, to allow rainforests and other rich habitats to recover. Where is the ambition our emergencies demand?

It does suggest more trees, but appears to believe that the only means of restoring them is planting. We have a national obsession with tree planting, which is in danger of becoming as tokenistic as bamboo toothbrushes and cotton tote bags. In many places, rewilding, or natural regeneration – allowing trees to seed and spread themselves – is much faster and more effective, and tends to produce far richer habitats.

All over the country, I see “conservation woodlands” that look nothing like ecological restoration and everything like commercial forestry: the ground blasted with glyphosate (a herbicide that kills everything), trees planted in straight rows, in plastic tree guards attached with cable ties to treated posts. It looks hideous, it takes decades to begin to resemble a natural forest and, in remote parts of the nation, it is often the primary cause of plastic litter, much of which is never recovered. There are no woodland creation grants in this country supporting natural regeneration: government money is pegged exclusively to the number of trees planted. This is one of the reasons for the shocking failure to meet the UK’s targets for new woodlands.

The government should follow the hierarchical approach suggested by the conservationist Steve Jones. It should fund natural regeneration wherever possible. Where trees struggle to establish themselves, it should finance assisted regeneration (clearing competing vegetation). Only where those options won’t work should it offer grants for tree planting. But while nature loves a mess, officialdom abhors one: instead of natural exuberance it seeks neat industrial rows.

Don’t expect much help from the government. Michael Gove’s successor as environment secretary, Theresa Villiers, seems tongue-tied, apparently terrified of offending vested interests. Labour’s vote for a Green New Deal, with a 2030 deadline for decarbonisation (20 years before the government’s) is exciting. Now we need to see its commitments on industrial emissions matched by ambitious proposals for ecological restoration.

Nor are the big conservation groups filling the void. Ours is an extraordinary situation: a nation of nature lovers, obsessed by wildlife programmes, represented by gigantic NGOs, but apparently incapable of preventing the precipitous decline of wildlife and habitats. The conservation groups have manifestly failed to translate our love of nature into action.

They betray their radical roots. The National Trust arose from the Commons Preservation Society, that tore down fences to return land to the people. Now it allows the forces it once contested to ride roughshod over its land, allowing trail hunts and exclusive grouse shoots to erode the sense of national ownership. On its Exmoor estate, in the resource book it publishes for school teachers, it celebrates burning the land. The RSPB was founded by women seeking to ban the import of birds’ plumage for hats – they eventually succeeded. Now, as independent ecologists raise massive petitions to ban driven grouse shooting, the RSPB undermines their campaigns by calling for this devastating practice to be, er, licensed. Hesitation and appeasement reign.

We should continue to mobilise against the destruction of the world’s great habitats, and its terrifying implications. But the most persuasive argument we can make is to show we mean it, by restoring our own lost wonders.