When Keir Starmer appointed Labour grandee Peter Mandelson as Britain’s ambassador to Washington in late 2024, the decision was sold as pragmatic statecraft. Mandelson was a known quantity: a veteran operator, fluent in elite power, and deeply networked in both Westminster and Washington. This, Starmer’s team implied, was not a risk but a qualification.

Less than a year later, that calculation collapsed.

In September 2025, Mandelson was abruptly dismissed after documents surfaced revealing the depth of his long-standing relationship with Jeffrey Epstein. These were not passing social encounters. The files detailed funded trips, extended hospitality, and a series of emails whose tone was unmistakably warm and personal. Mandelson insisted there was nothing improper, but the revelations detonated the core claim on which his appointment rested: that he had been properly vetted.

That claim has only grown more fragile. In early February 2026, newly released U.S. Justice Department files reignited scrutiny of Mandelson’s role and the UK government’s due diligence. British police subsequently raided multiple properties linked to him, escalating what had been a political embarrassment into a full-blown institutional crisis. Starmer, visibly shaken, issued a statement expressing “deep regret” over the appointment and conceded that the vetting process had “clearly failed.”

For many observers, the scandal has felt eerily familiar. So familiar, in fact, that many now turn not to Hansard or government white papers, but to a clip from Yes, Prime Minister.

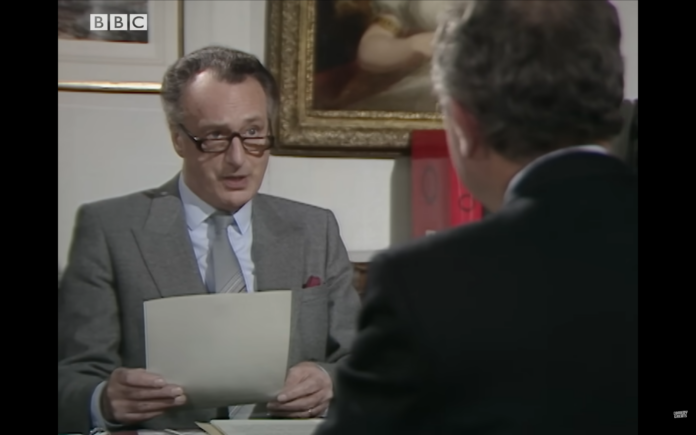

The clip, from the episode “One of Us,” features Sir Humphrey Appleby calmly explaining why the British establishment failed to detect that a senior civil servant was a Russian spy. The reason is not incompetence but trust, specifically, trust reserved for the right sort of people. The spy, Sir Humphrey explains, went to the right school, mixed with the right circles, and belonged to the right clubs. He was, in the most important sense, “one of us.” That, paradoxically, made him invisible to scrutiny.

The scene is played for laughs. But its logic is deadly serious.

What the Mandelson affair has exposed is not simply a personal lapse, but a structural one. Vetting systems that are ferocious when applied to outsiders become strangely indulgent when directed inward. Elite networks, by their nature, are assumed to be self-policing. Familiarity substitutes for verification. Reputation replaces evidence. The question “Should we check?” is quietly overridden by “Surely we already know.”

This is precisely the pathology Sir Humphrey describes. Power in Britain, he suggests, does not really operate through rules but through recognition. If you are recognised as belonging, the rules bend. If you are recognised as respectable, suspicion dissolves. Mandelson’s career, his survival through multiple scandals, his perpetual returns to influence were built inside that logic. It ultimately became its undoing.

What makes the episode’s renewed popularity so striking is not that a sitcom “predicted” events, but that it articulated a truth British politics has long refused to confront: elite failure is not accidental. It is systemic. It arises from a culture that confuses social pedigree with moral reliability and proximity to power with probity.

Starmer’s expression of regret, however sincere, does not resolve that deeper problem. Mandelson was not an anomaly smuggled past the gatekeepers. He was the gatekeepers’ idea of safety. That is why the checks were light. That is why the warning signs were missed. That is why, when the scandal broke, the public reaction was not shock but recognition.

“Yes, Prime Minister” was never really a comedy about bureaucracy. It was a satire about class, access, and the quiet agreements that govern who is trusted and who is scrutinised. Decades on, its Russian spy sketch now circulates as something closer to documentary than farce.

The joke, it turns out, was never that the system failed.

The joke was that it worked exactly as designed.