In Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel, a poignant observation stands out: “It is the absence of facts that frightens people: the gap you open, into which they pour their fears, fantasies, desires.” This encapsulates a fundamental truth about the human condition. When confronted with the unknown, we instinctively fill the void with conjecture, projections, and personal biases. The statement reveals our discomfort with ambiguity and underscores the human tendency to create meaning where there is none. The implications of this observation resonate deeply with our pursuit of knowledge, its limitations, and its consequences.

The vacuum described by Mantel highlights both the necessity and futility of our search for certainty. Knowledge, while infinite in scope, is cocooned by the inherent limitations of the human mind. We explore, discover, and classify, yet our efforts are never enough to satisfy the hunger for ultimate comprehension. The vastness of the unknown dwarfs even our most significant intellectual breakthroughs, leaving us to grapple with the question: how much can we truly know, and what does it mean to know anything at all?

The Illusion of Factual Certainty

Human beings are pattern seekers. We crave order, predictability, and a coherent narrative to make sense of our existence. The absence of facts creates a psychological vacuum, into which our imaginations readily flow. This tendency explains the proliferation of myths, conspiracy theories, and speculative fiction—our minds resist the idea of a blank space.

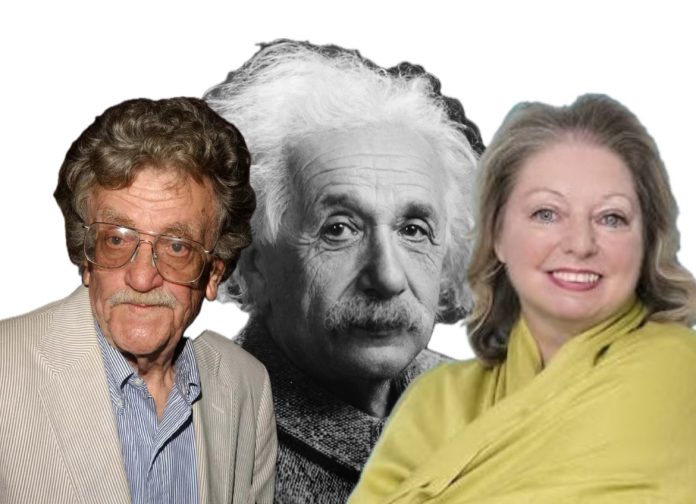

However, facts alone do not offer the solace we seek. Facts are fragments, isolated pieces of a larger puzzle. Without context and understanding, they lack meaning. Albert Einstein astutely observed, “Any fool can know. The point is to understand.” Knowledge, stripped of comprehension, is sterile. It is through understanding—the process of synthesising facts, recognising patterns, and contextualising information—that we find purpose and insight.

The Paradox of Infinite Knowledge

The infinite nature of knowledge presents a paradox. On one hand, it is empowering; we live in an era of unprecedented access to information. On the other hand, it is overwhelming, for the more we know, the more we realise how little we understand. The concept of infinity in knowledge implies that there will always be more to uncover, more to question, and more to explore. Relatively speaking, any level of knowledge we achieve is minuscule compared to the vastness of the unknown.

This infinite expanse can be both inspiring and debilitating. For some, it fuels curiosity and a relentless pursuit of discovery. For others, it evokes existential despair, as the pursuit of ultimate knowledge seems futile. The latter sentiment is encapsulated in Kurt Vonnegut’s warning: “Beware of the person who works hard to learn something, learns it, and finds themselves no wiser than before.”

Vonnegut’s statement is a cautionary tale, urging us to reflect on the purpose and consequences of our intellectual pursuits. What happens when our hard-earned knowledge fails to deliver the clarity or wisdom we expected? This dilemma raises three critical considerations about the nature of knowledge: its relativity, its sources, and its application.

Relativity in Knowledge

Vonnegut’s assertion that “any level of knowledge is no more than any other” may initially seem counterintuitive. Yet, when viewed through the lens of infinity, it becomes clear that knowledge is inherently relative. Our greatest discoveries are but drops in an ocean of the unknown. The relativity of knowledge challenges us to adopt humility in our intellectual pursuits. It reminds us that what we consider groundbreaking today may one day be viewed as rudimentary.

Take, for instance, the history of scientific progress. For centuries, humanity believed in a geocentric universe, only to have that belief overturned by the heliocentric model. Even now, our understanding of the cosmos is constantly evolving. Each new discovery reshapes our perspective, illustrating the transient nature of what we “know.” This relativity is not a weakness but a testament to the dynamic and self-correcting nature of human inquiry.

The Flaws in Our Sources

The infinite nature of knowledge is compounded by the imperfections in our sources. Human understanding is shaped by language, culture, and personal experience, all of which are riddled with biases and agendas. History, for example, is often written by the victors, leaving the perspectives of the defeated obscured or distorted. Similarly, scientific research is influenced by funding priorities, political considerations, and societal values.

In the digital age, these biases are amplified by the sheer volume of information available. The internet, while a powerful tool for dissemination, is also a breeding ground for misinformation and propaganda. Algorithms prioritise engagement over accuracy, creating echo chambers that reinforce existing beliefs. In this environment, distinguishing fact from fiction becomes increasingly challenging.

The flaws in our sources highlight the importance of critical thinking. To navigate the labyrinth of information, we must approach knowledge with a healthy scepticism, questioning not only the content but also the motivations behind it. As the philosopher Karl Popper argued, the hallmark of scientific progress is not certainty but falsifiability—the ability to question and revise our beliefs in light of new evidence.

The Responsibility of Knowledge

The third and perhaps most profound consideration is what we do with what we think we know. Knowledge, like power, carries responsibility. How we apply our understanding shapes the world around us, for better or worse. The ethical dimensions of knowledge are evident in fields such as medicine, technology, and environmental science, where the consequences of our actions are far-reaching.

For instance, advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have the potential to revolutionise industries, improve healthcare, and address global challenges. Yet, they also raise ethical concerns about privacy, bias, and the displacement of human labour. Similarly, breakthroughs in genetic engineering offer the promise of curing diseases but pose questions about eugenics and the commodification of life. In these cases, the pursuit of knowledge must be tempered by a consideration of its implications.

Reconciling Knowledge and Wisdom

The tension between knowledge and understanding brings us to a critical distinction: the difference between knowledge and wisdom. Knowledge is the accumulation of facts and information; wisdom is the ability to apply that knowledge judiciously. Wisdom requires humility, empathy, and an awareness of the broader context.

One way to cultivate wisdom is through interdisciplinary thinking. By integrating insights from diverse fields, we can develop a more holistic understanding of complex issues. For example, addressing climate change requires not only scientific expertise but also an understanding of economics, politics, and human behaviour. Similarly, resolving social inequalities demands a synthesis of historical, cultural, and psychological perspectives.

Another path to wisdom is through introspection and self-awareness. As Socrates famously declared, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” By reflecting on our beliefs, values, and assumptions, we can identify the gaps in our understanding and strive for a more nuanced perspective. This process is not about achieving certainty but embracing ambiguity and complexity.

The Pursuit of Meaning

Ultimately, the quest for knowledge is inseparable from the search for meaning. As finite beings in an infinite universe, we are driven by a desire to make sense of our existence. This drive manifests in art, philosophy, religion, and science, each offering a different lens through which to view the world.

Yet, meaning is not something to be discovered; it is something to be created. As the existentialists argued, life has no inherent meaning, but we have the freedom and responsibility to define our own purpose. This perspective shifts the focus from what we know to how we live. It challenges us to use our knowledge not as an end in itself but as a tool for personal growth and social progress.

The infinite nature of knowledge, as highlighted by Hilary Mantel, Albert Einstein, and Kurt Vonnegut, is both a source of wonder and a reminder of our limitations. It invites us to question the boundaries of our understanding, the reliability of our sources, and the implications of our actions. In doing so, it calls us to move beyond the accumulation of facts and towards a deeper comprehension of ourselves and the world around us.

In the end, the pursuit of knowledge is not about conquering the unknown but about navigating its vastness with curiosity, humility, and purpose. It is about recognising that the gaps in our understanding are not merely voids to be filled but opportunities for growth and discovery. And perhaps, as Vonnegut cautions, it is about finding wisdom in the realisation that knowledge, no matter how hard-won, is only as meaningful as the context and purpose we give it.