If you tell someone, “This is the right thing to do,” but you are asked, “Why? Why’s it the right thing to do?” you might respond, “Because that’s what morality tells us to do.”

Your objector may still ask, “But why should I do what morality dictates?”

Given our discussion about the nature of morality in the previous articles in this series, you might answer, “Because morality is the glue that holds society together, the reason why we can trust each other, a basis for cooperation and mutual endeavour. It’s the second greatest invention humanity has ever made. It’s a Universal Sentience Unification System and without it our community or nation or civilisation is likely to tear itself apart.”

To my mind, this is a good enough reason to be moral… but some people may want more.

After all, the way we use moral language suggests that there is something profoundly authoritative and compelling in the language of moral judgments.

Universal scope

When someone says to you, “That is what you ought to do,” it carries a degree of authority which suggestions like, “That is what I want you to do,” or “Do it because I’m telling you to,” simply don’t possess.

My physical threat or personal entreaty are localised and personal and lack the universal scope and authority of the moral ought.

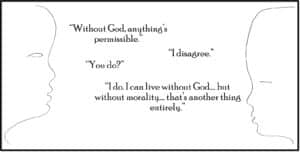

Godless

So where might we look for the power behind the ‘ought’? What gives moral statements their imperative force?

In the past God has been used for this purpose – to back up moral claims and provide them with a seemingly indisputable power. “Why is this the right thing to do? What a stupid question! It’s because God says so.”

However, this is an answer we can no longer use. In a modern context, as a justification for moral authority, God is problematic.

Why?

Because:

-

- Many of us have stopped believing in any form of God or gods.

-

- Many of the rules once enforced in the name of ‘divine authority’ have proven to be arbitrary, inconsistent, prejudicial against minorities or gender, extreme or unjust.

-

- Gods are local, specific to one culture or another – but morality transcends culture. As we saw in the first article in this series, the concept of morality requires universality. Anything else is just individual whim or cultural norm.

- Morality applies whether there is a God or not.

So, without God, where can morality find its imperative force? To what form of authority might a rational, universal morality appeal?

The system

The essential characteristics I identified in the first article in this series offer some clues. They suggest that morality’s source of authority:

-

- Has to transcend the individual.

-

- Needs to be greater than any group, community, culture or even civilisation.

-

- Needs to be accessible to any autonomous sentient.

Can’t be local, based on local traditions, beliefs or myths.

Morality’s source of authority must be something we all have in common – something which is objective not subjective, factual not mythical, substantive not ethereal.

So what source of authority might satisfy these criteria?

Epiphany

To begin with, we can exclude intuitions, inner voices and epiphanies.

Intuitions can vary between individuals, let alone between cultures and civilisations… and inner voices and epiphanies say different things to different people.

If the authority you are appealing to is home-grown and dependent on personal intuition or insight it will by definition lack the requisite universality and power. It becomes little more than shorthand for “What I want” or “What I’d prefer”.

Moral authority cannot derive from what an individual might want or what communities, nations or even societies might choose to do. It has to derive from something more universal, with a more profound imperative force.

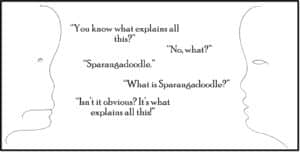

Magic dust

Concepts constructed by specific cultures or groups also fall short of our needs. ‘Divine purpose’, ‘intelligent design’, ‘human nature’, ‘the historical imperative’, ‘economic necessity’, ‘the power of love’ – none of these satisfy the universality required by a sentience unification system. In some cultures these concepts would be meaningless. In others they would be disputed or dismissed.

Worse, many of these concepts invoke what the philosopher Daniel C. Dennett calls ‘magic dust’ – namely, intangible or magical entities invented to answer some dilemma or question, and which normally can’t be measured or disproved.

If we are looking for a source of moral authority which is applicable anywhere, at any time, we need something better.

The source

But what can this better source of authority be?

There is an obvious candidate. In fact, it’s blindingly obvious.

It’s something we all share.

It’s tangible, accessible, appealing, inspiring and always there.

It’s both empirical and experiential.

Among sentients it’s universal.

By the standards of individuals it’s more or less eternal.

It looks back at us from the mirror.

It’s in us.

It’s outside of us.

It is us.

Do you like my riddle?

Have you guessed it already?

The answer is, of course, life.

Life is powerful, awe-inspiring, magnificent, tenacious. It is the origin of meaning, purpose and agency in an otherwise meaningless universe.

Life is what every living being shares. It imbues our every living moment.

Life is the source of everything we are, the source of everything we do.

So, if we require a compelling source of moral authority, what better candidate can there be?

What better imperative can we find for a universal sentience unification system than the imperative of life?

Our alien friends

Morality is a tool – a universal sentience unification system.

Installing a reverence for and a commitment to life as the motor for this tool gives it additional power or torque. It gives us an emotional or even spiritual connection to what this ultimately rational tool is for: unity, unification, establishing trust.

If an alien species were to fly past our planet and observe its inhabitants revering life and utilising a universal sentience unification system to unite races, cultures, and nations, our alien friends might say, “Fancy a stopover? Humans look like folk we can work with…”

That’s the point of a USUS. It can unite us with aliens too.

If, on the other hand, they found a planet with a decaying, amoral civilisation, rife with cruelty and tearing itself apart at the seams, our UFO friends might choose to pass us by.

If they were sensible, they might leave a sign for other travellers:

DANGER – AVOID UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE

In my next article in this series, published on Dorset Eye tomorrow, I look at whether the nature and purpose of morality determine its content. Does what morality is and what it is for constrain what anyone can claim it says?

Luke Andreski

Luke Andreski is a founding member of the @EthicalRenewal and Ethical Intelligence collectives. His books include Intelligent Ethics (2019), Ethical Intelligence (2019), Short Conversations: During The Plague (2020) and Short Conversations: During the Storm (2021).

Intelligent Ethics is available here.

With thanks to Betty Wills for the beautiful squid image, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

You can connect with Luke on LinkedIn, https://uk.linkedin.com/in/luke-andreski-ethics, or via @EthicalRenewal on Twitter https://twitter.com/EthicalRenewal

Join us in helping to bring reality and decency back by SUBSCRIBING to our Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQ1Ll1ylCg8U19AhNl-NoTg and SUPPORTING US where you can: Award Winning Independent Citizen Media Needs Your Help. PLEASE SUPPORT US FOR JUST £2 A MONTH https://dorseteye.com/donate/

You can find the preceding article in this series here: https://dorseteye.com/what-morality-is/

“Where power and wealth are not distributed equally scenarios of unfairness are created which directly conflict with the nature of morality: its presupposition of freedom, its universality and its affirmation of equality.”

Read the next article in my Morality Series here on Dorset Eye:

https://dorseteye.com/what-morality-says/