For many people in Dorset, this winter has blurred into a single, grey stretch of damp days. Rain has fallen again and again, often without drama, but with a persistence that has slowly worn down rivers, roads and patience alike. Fields remain sodden, chalk streams are running high, and surface water now gathers after even modest showers.

Rain has fallen somewhere in Dorset every day so far in 2026. January finished around fifty per cent wetter than the long-term average, placing it among the wettest Januarys the county has experienced since modern records began. February has followed the same theme, with forecasters warning there is little immediate sign of a prolonged dry spell.

Dorset is used to rain. Its position on England’s south-western edge puts it directly in the path of Atlantic weather systems, and its rolling downs help wring moisture from passing clouds. In an average year, most of the county receives between 800 and 1,000 millimetres of rainfall, with higher totals inland and on elevated ground. Winter is always the wettest season, but this winter feels different.

The difference lies not just in how much rain has fallen, but in how rarely it has stopped.

Historically, even wet winters in Dorset contained pauses. Rainy spells were broken by dry days that allowed rivers to fall back and soils to drain. This year, those gaps have been scarce. Near-daily rainfall has left the land saturated, meaning water now runs straight off fields and roads instead of soaking in. Flooding risk builds faster, even without extreme downpours.

To understand how unusual this is, it helps to look back.

January rainfall in Dorset, compared across time

| Period | Typical January rainfall (relative) | Context |

|---|---|---|

| 1901–1930 average | ~90 | Drier winters, fewer extremes |

| 1961–1990 average | ~95 | Gradual increase |

| 1991–2020 average | 100 | Modern baseline |

| Wettest Januarys (top 10%) | ~130 | Historically notable |

| January 2026 | ~150 | Among the wettest on record |

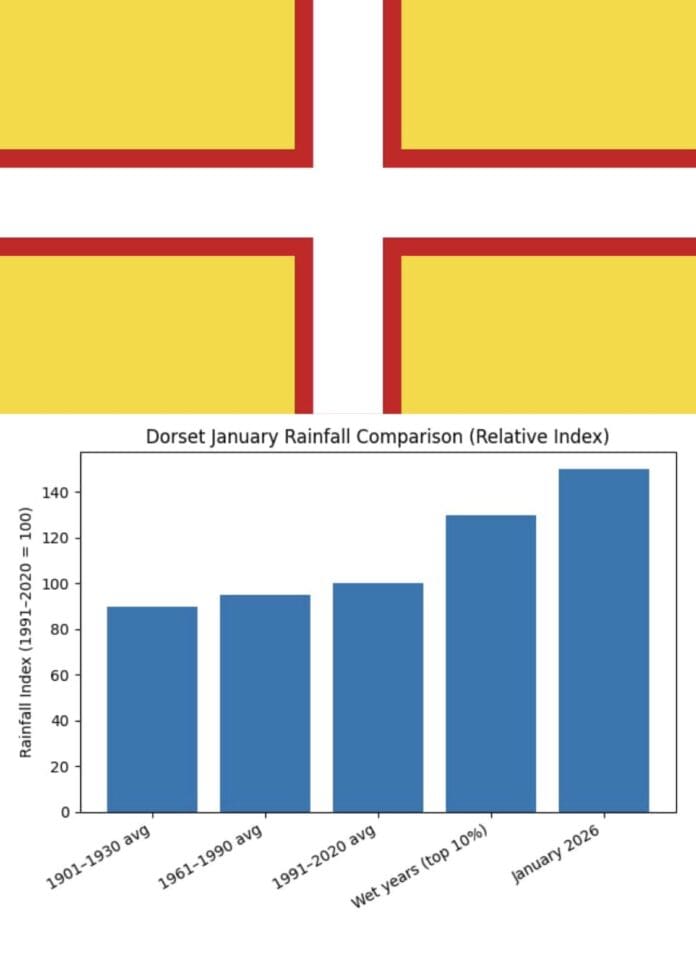

These figures show that January 2026 sits well beyond what would once have been considered a “very wet” winter month. While Dorset has seen individual storms deliver intense rainfall before, the accumulation this year is what pushes it into the upper reaches of the historical record.

The graph above illustrates the same pattern visually. Using the modern 1991–2020 average as a baseline, January 2026 stands out sharply, even when compared with other exceptionally wet years. This is not a marginal difference; it is a step change.

Rainfall totals, however, only tell part of the story. Frequency matters just as much.

How often it rains in a Dorset January

| Era | Typical proportion of rain days |

|---|---|

| Early 20th century | 60–70% |

| Late 20th century | 70–80% |

| 2026 | Almost 100% |

This near-unbroken run of wet days explains why the impacts feel so severe. Rivers rise more quickly, drains struggle, and the landscape never gets a chance to reset.

The causes lie far beyond Dorset itself. A persistent area of high pressure has been sitting to the north and east of the UK, acting as a block. Rather than allowing weather systems to pass through, it has forced Atlantic fronts to slow, stall and repeatedly reform over southern Britain. At the same time, the jet stream, the high-altitude current that steers storms, has shifted south of its usual winter position, guiding rain-bearing systems directly towards Dorset.

There is also a longer-term backdrop. Over the past century, Dorset’s climate records show winters becoming wetter overall. A warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, meaning that when rain does fall, it is more likely to be prolonged and heavy. This does not create rain on its own, but it amplifies the effects of already unsettled weather patterns.

The result is a county that is increasingly vulnerable to cumulative rainfall rather than headline-grabbing storms. Minor rivers respond faster, low-lying roads flood more easily, and agricultural land takes longer to recover. For residents, the disruption feels constant rather than episodic.

Looking ahead, forecasters remain cautious. Rain may ease at times, but until the broader atmospheric pattern shifts, Dorset remains exposed. The winter of 2026 is not unprecedented, but it is a clear example of how the county’s familiar wet climate is edging into more extreme territory.

For Dorset, long shaped by water, the lesson from the past hundred years is increasingly clear: it is not just raining more; it is raining more often, and with fewer breaks in between.