My first best friend was a Jewish kid. He lived next door to me and, being a year older than me, was my absolute hero. I used to follow him around, and although I did not really understand it, I was aware of his Jewishness. Later, after we had moved away, we came back to go to his bar mitzvah, and I can always remember finding the five-pound note and being very proud. Not long afterwards, I went on a school trip to Lightwater Valley, and there were some Hasidic Jewish children in the queue. I heard one of our classmates call them ‘yids’. It instantly sent a shiver down my spine, and I was upset and angry when I got home, though again not understanding fully.

Growing up, our house was full of people from all over the world. My mum was a TEFL teacher, and we had a constant stream of people from Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, Zimbabwe, Iran and China. It seemed like almost every weekend, there would be some party with incredible food from different parts of the globe and chatter about politics. Many of them were asylum seekers and refugees, and I would strike up conversations with them and learn about their world. I remember clearly one time when two guys from Southern Africa (I think it may have been Mozambique) found out that I was a Bob Marley fan, and the next week one of them had gone out to buy an LP, ‘Survival’ for me—incredible for someone who would have had very little money at the time. Even at that age, I knew what that meant, though. It was an act of solidarity and anti-racism. I learned so much from those early experiences.

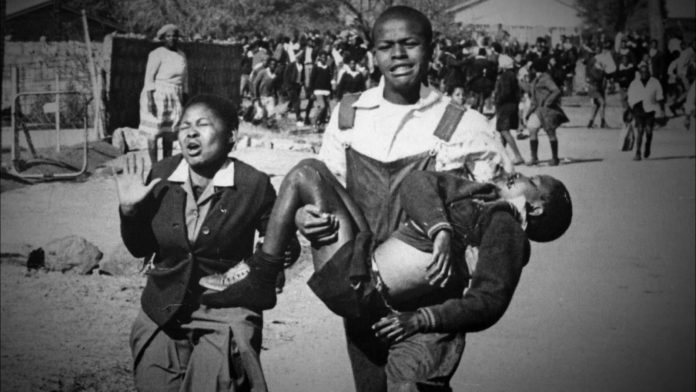

As a teenager and as someone who’d been surrounded by people of so many nationalities, I was immensely affected by images I saw on the news, in films, and in the papers from Apartheid South Africa. Even learning about Sharpeville, the Soweto Uprising, and the Rivonia trials felt like living history because I knew it was still happening. I was reading about it and absorbing that anger at racism and injustice into my very soul. I’d become an anti-racist long before I became a socialist.

Around the age of 13/14, I decided that I needed to do something. I became involved in the anti-apartheid movement, going to meetings in Durham and joining marches as they wound their way through the North East on the way to London. One weekend, I cajoled my little sister to make a big banner out of a bedsheet. It’s said: ‘Hey, Botha. Don’t mess with my Tutu!’. We took it down, on a coach by ourselves, to a big demonstration in Hyde Park where Desmond Tutu was speaking, and to this day I’m convinced that he acknowledged it as we struggled to raise it between ourselves, in amongst the crowds.

In the following years, I read Biko, Malcolm X, and even tried some Frantz Fanon. This stuff really interested me and excited me, but it led me to socialism and Marxism, not the other way around. By the time I got to university, I knew I was a socialist and started hanging around with the paper sellers, eventually joining Militant (they seemed more interested in life beyond the student union). One of the things that disturbed me, though, was that (maybe subconsciously), issues of race were often subsumed under a catch-all call to’unite the working class’. That seemed to me to be ignoring the needs of the black and ethnic minority communities to address their own specific oppression. I felt uncomfortable with all that, and partly as a result, I didn’t stick around too long.

At Leeds University and after, I threw myself into anti-racist campaigning. Confronting the far right en masse seemed like an important and powerful expression of solidarity. In these years, I found it difficult to find a political home. I joined and left the Labour Party, joined and left the Socialist Alliance, and ended up back in Labour again, only to leave over the Iraq War and rejoin after Blair. Throughout that time, however, my anti-racism was a constant. I organised, small and big, and discussed how we could build anti-racism in the Labour Party, in unions, and in communities, so it wasn’t an add-on but something integral to who we are.

At times over that period, within the Labour movement, it was a bit of a lonely place to be. As New Labour took hold, fewer and fewer Labour MPs wanted to do the demos, develop broad left alliances, and actively work in communities. Only the Socialist Campaign Group of Labour MPs would regularly come out to support us, and out of that group, Jeremy Corbyn would almost always be the first and most constant supporter. Amongst the party (and union) hierarchy, on the other hand, there became a stigma attached to big anti-racist mobilisations and I recall hearing Labour councillors say that a physical presence should be avoided, as it was just “picking at a wound.”.

I became a trade union organiser myself and specialised in supporting migrant workers to achieve their rights by joining trade unions. As Gordon Brown was talking about ‘British Jobs for British Workers’, I was organising with Polish immigrants and refugees. At the same time, I made myself unpopular with some in the union hierarchy by arguing that sectarianism and factionalism should be left at the door when campaigning against the ever-increasing threat of the BNP. In truth, though it was probably for the best, my union career was ended by the stance that I took.

While I started a PhD on trade unions and migrant workers, which covered the Imperial Typewriters strike in Leicester by Ugandan Asian women in the 1970s, I also threw myself back into grassroots anti-racist organising. I helped set up the County Durham Anti-Racist Coalition with a couple of friends. The group later went on to organise one of the biggest demonstrations ever seen in Durham against the visit of the far right under the banner ‘Bishop Auckland Against Islam’. 300 filled Millenium Square. Set against the safe and inconsequential ‘box-ticking’ anti-racism that has become commonplace in our movement—e.g., a pop-up stand in the corner of County Hall—this was where I felt at home.

Racism made me angry as a kid, long before I understood socialism and the economic chains that bind all of us. This is a story common to many of us on the left, and especially those who have come into the Labour Party since 2015 – and who frankly will have seen the party’s efforts as inadequate pre-Corbyn and perhaps understandably so (David Blunkett’s punitive and uncaring approach to immigration, Phil Woolas’ behaviour, and those bloody immigration mugs being a handful of recent examples).

I make mistakes. Like everyone in this movement, I get things wrong. When I do, I kind of expect to be called out on it. If it’s justified, I will try to reflect on it. That is fair and right. This is politics; debate is part of the lifeblood of the party and the movement, and of you can’t take criticism, it may not be for you. However, that is a very different thing from throwing around the word ‘racist’ or ‘antisemite’ as a way of scoring political points, when even the accuser knows in their hearts that it’s unfair and wrong. So, call me what you like, criticise my decisions and pull me up for my mistakes. Rip into my politics and question my outlook. But don’t ever call me a racist.

Join us in helping to bring reality and decency back by SUBSCRIBING to our Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQ1Ll1ylCg8U19AhNl-NoTg SUPPORTING US where you can: Award Winning Independent Citizen Media Needs Your Help. PLEASE SUPPORT US FOR JUST £2 A MONTH https://dorseteye.com/donate/