The latest tranche of documents released by the US Department of Justice should end, once and for all, any lingering indulgence towards Peter Mandelson. They reveal not merely poor judgement, but a pattern of proximity to power, money and moral collapse that is wholly incompatible with public life.

The emails show Lord Mandelson assuring Jeffrey Epstein that he was “trying hard” to amend UK government policy on bankers’ bonuses at Epstein’s request in December 2009. This was not a trivial matter. The country was still reeling from the financial crash; banks had been rescued with public money; anger over bonuses was widespread and justified. Only days earlier, the chancellor had announced a 50 percent super-tax on bonuses to curb excess and restore public trust. Yet here was a senior cabinet minister privately lobbying to weaken that policy at the behest of a disgraced financier.

This would be troubling enough on its own. But it is rendered far darker by the surrounding context. Just months earlier, Epstein, recently released from prison after pleading guilty to trafficking a minor, had transferred £10,000 to Lord Mandelson’s husband following a direct request for financial support. The correspondence is explicit. The money arrived. Thanks were given. And shortly afterwards, Epstein was back in confidential contact with a cabinet minister about shaping government policy in the interests of the financial elite.

This is the very definition of the revolving door culture that has hollowed out trust in politics. No allegation needs to be exaggerated; the facts are damning in their own right. A convicted sex offender with deep ties to global finance had privileged access to a senior UK minister, and that minister appears to have acted on his behalf while his household benefited financially.

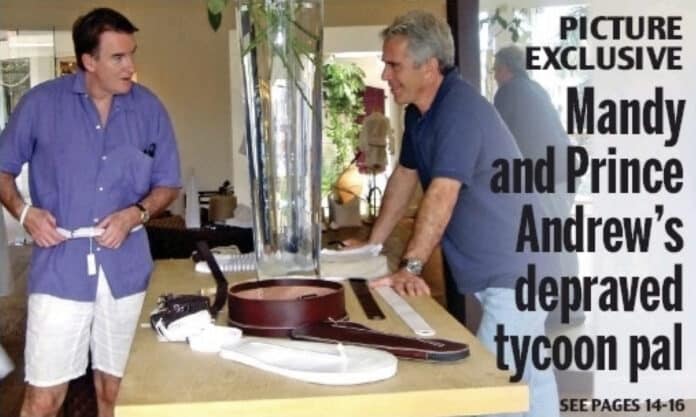

The emails also expose the broader nature of the relationship. Mandelson and Epstein discuss election prospects, media narratives, career options, and even potential international appointments. They arrange meetings, joke about journalists, and speculate about roles at Facebook and the IMF. This was not a passing acquaintance. It was a sustained, comfortable closeness between power and corruption.

Supporters of Mandelson will no doubt argue that no law has been proven to be broken. But politics is not merely about legality; it is about standards, ethics and trust. A life peer is supposed to embody public service. A senior Labour figure should be guided by solidarity with the public, not private assurances to financiers seeking to dodge accountability after crashing the economy.

Labour, in particular, cannot look the other way. A party that claims to stand for working people cannot tolerate figures who privately undermine measures designed to restrain the excesses of bankers, especially when doing so in dialogue with a man whose name has become synonymous with exploitation and abuse.

Peter Mandelson should not simply fade quietly into the background. His lordship should be revoked, and he should be formally barred from any role in party politics. Anything less signals that there is one set of rules for the powerful and another for everyone else.

If politics is ever to regain credibility, it must be willing to draw hard lines, even, and especially, when they cut through the old establishment.