As the lights change at a major crossroads in a city in the heart of Europe a car grinds to a halt. Its driver can drive no more. Suddenly, without warning or cause, he has gone blind. Within hours it is clear that this is a blindness like no other. This blindness is infectious. Within days an epidemic of blindness has spread through the city. The government tries to quarantine the contagion by herding the newly blind people into an empty asylum. But their attempts are futile. The city is in panic.

Award-winning playwright Simon Stephens has adapted Nobel Prize-winner José Saramago’s dystopian novel Blindness as a sound installation, directed by Walter Meierjohann with immersive binaural sound design by Ben and Max Ringham. Juliet Stevenson voices the Storyteller/Doctor’s wife in this gripping story of the rise and, ultimately, profoundly hopeful end of an unimaginable global pandemic.

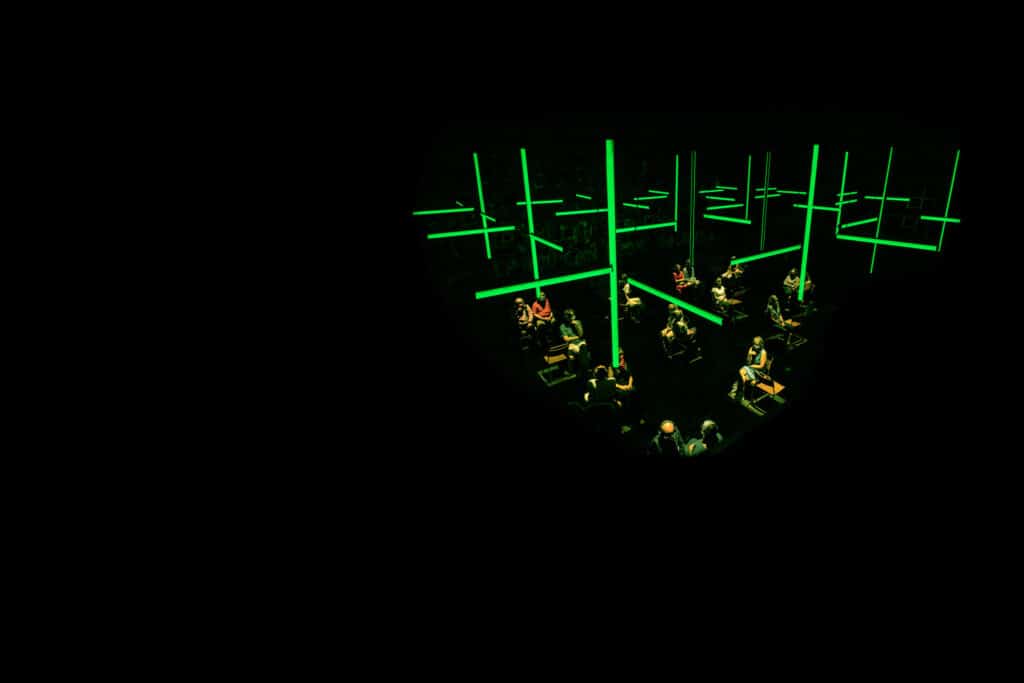

This ticketed installation for a limited number of visitors runs four times a day, with seating arranged 2m apart in accordance with social distancing guidelines. Visitors will listen on headphones as the narrative unfolds around them.

A Q&A interview, produced exclusively for Lighthouse, with acting royalty Juliet Stevenson who plays the Narrator/Doctor’s Wife in the acclaimed Donmar Warehouse production of Blindness that plays four shows a day at Lighthouse from 13 to 17 July.

1. Nobody could have imagined how prescient José Saramago’s novel and, indeed, the play would be – how did that make you feel?

Saramago’s novel tells the story of a town struck by an epidemic of blindness. Of course, it’s extremely prescient, but we actually started working on Simon Stephens’ stage adaptation with director Walter Meierjohann before any of us had even heard of Covid.

We started work on it in 2019 and during that workshop period, we saw the epidemic of blindness as an interesting interpretation of Brexit. At that time, you could really feel Brexit fever as anger and division ripped through the country. The story acts as a metaphor that could be layered on to all kinds of situations but 2019 was such a ferocious year for Brexit, that was how we interpreted it.

When the opportunity arose to stage Blindness at the DonmarWarehouse as a sound installation, my first thought was that we couldn’t possibly do it because you can’t do a play about a real virus when the story acts as this metaphor. It felt almost too prescient, and I wondered if anyone would want to go to the theatre to experience this installation in the middle of an actual pandemic. But I was wrong. Although it isn’t actually the story of Covid, I think people found themselves listening to this fiction that was so extraordinarily descriptive of some version of their own lives with the isolation and the panic, that it was a sort of consolation or comfort. The story has anoptimistic ending, which I think gave people hope.

2. How did you prepare for the role?

We began workshopping Simon Stephens’ stage adaptation of Blindness at the National Theatre Studio in 2019. The National Theatre Studio is a part of the National where they workshop new writing and facilitate up and coming playwrights and they asked me to come and do a workshop for a week. I’m a huge fan of Simon’s work and this was such fascinating material, I knew I had to do it and said yes. In that first workshop, there were about 25 of us. All of us in that big cast worked together for a week before showing the work to producers and other industry people on the Friday afternoon.

As a result of that process, I was already familiar with the piece when we picked it up again last July but there was this huge difference in staging it as a sound installation with one voice rather than a live performance with that large cast of 25.

3. What was the rehearsal and recording process like for BLINDNESS? How did the process differ to a live production?

It was a 10-day process and, honestly, it was the most thrilling 10 days I’ve spent making a piece of theatre. We started with no idea of how we were going to tell this story as a sound installation, and it was just so thrilling to be in this room where everything was new. Even wonderful Ben and Max Ringham, our sound designers who crafted the installation’s soundscape, hadn’t worked in this way before, using the binaural sound recording technology.

We had so little time and had to work really fast but as is often the case, it was a hugely creative process. We just had to dive in and make brave, experimental choices and that’s what we did from the word go.

The first challenge was working out how the technology worked. For binaural sound recording, you have a human head, made from fibreglass or something similar, with two microphones placed inside the head, one in each ear. We had to spend time working out all the different effects we could create with me interacting with the dummy in different ways. What happens if I lie down next to the dummy? What happens if I whisper in its left ear? What happens if I walk around it, talking quietly? How far away can I go and shout back at it. We would constantly experiment and listen back to what we’d recorded to see what worked and what didn’t.

Some parts of the story were really difficult. There are scenes where hundreds of people are trying to break into the hospital ward where my character, the Doctor’s wife, has been sent with all the people affected by the epidemic of blindness. All these people are trying to break into the ward to find space and she’s trying to keep them out, shouting and hurling things at them and trying to barricade the door to protect her people.

I saw a pile of chairs in the corner and just started throwing them across the room, one after the other in quick succession. We played the recording back and it was extraordinary to hearhow that sound of the chairs crashing to the floor told that story so completely. The energy of the attack and frantically piling up the hard, metallic furniture to block the entrance, that story was told in sound terms.

As well as creating these physical sounds, I worked with director Walter Meierjohann and Ben and Max to work out how to give the impression of many more people being present when there was only me to play the scene, thinking about how to make it clear what someone else is saying when they’re not there to say it. I also thought a lot about the tone and quality of my voice. How does your voice alter when you’re talking to a child or someone you don’t know well or someone you know intimately? The fine gradations of how we speak to one person as opposed to another all came into play.

Over the ten days, everyone just jumped into everyone else’s department. It was so collaborative with everyone bringing their ideas and it was just so thrilling to be a part of a process that was so different to every other production I’ve worked on.

4. BLINDNESS was first performed at the DonmarWarehouse when restrictions were much tighter. What are you looking forward to now that restrictions are starting to ease?

I’m really looking forward to returning to theatre and it beingsafe to do so. Like so many people, I’ve missed that feeling of being part of a live event and it is so reassuring to see theatres reopening and venues putting so much thought and care into how to keep audiences secure.

I also really hope that we learn something from this period of restrictions. When something is taken from you, you really learn its full value. It will be great if we come back to theatre and really ask: ‘what is it for?’. That way we will create work that really gives something to audiences and hopefully helps them feel that they want to return.

5. What role do you think theatre and the arts will play in our recovery?

Throughout so much of the pandemic, we’ve all had to focus on the practical things such as how we can protect each other and stop the spread of the virus. Now, we all need some reassurance to return to a less restricted way of living. The experience of the last year has really taken the toll on our mental health as the separation from community has left so many people feeling extremely lonely. I think the arts have a key role to play in bringing people back together and reducing that sense of isolation.

In this time we’ve all been driven to our screens and, although the virtual world has been a great source of stimulus and comfort, there is a danger that when people live their lives online, they are depriving themselves of the quintessential human need for touch and physical contact. We all keep saying, ‘gosh, we’ve missed hugs’, and hugs are really a metaphor for being with people and being part of a community.

There are so many stories to tell from and about the pandemic and what we’ve all lived through. I think the arts can play a vital role in telling those stories and bringing people back together.

6. What advice would you give to emerging artists?

In relation to the pandemic, I’d say, make work however you can and use the restrictions as a springboard to make that work.

Artists of all kinds in every area of the arts have always used adversity and difficulty and, sometimes, amazing work comes out of those difficult situations. Even if you have just a tiny window of opportunity, you can make things happen.

That’s not an argument for being under-resourced but, if you can’t do things in the usual way, you simply have to find different ways to make work. That’s what Blindness was, a completely new way of making work but it’s certainly not the only example. I’ve been totally bowled over by what people have achieved in their own front rooms. I would say, follow your instincts, be true to yourself and follow your intuition. Be brave, be challenging and don’t follow anyone else’s mantra. Don’t be confined by the politics of the time; be true to yourself, whatever that self is, and make work from the centre of who you are.

Juliet

Blindness and Covid:

Although it isn’t actually the story of Covid, I think people found themselves listening to this fiction that was so extraordinarily descriptive of some version of their own lives with the isolation and the panic, that it was a sort of consolation or comfort. The story has an optimistic ending, which I think gave people hope.

Making the show:

We had so little time and had to work really fast but as is often the case, it was a hugely creative process. We just had to dive in and make brave, experimental choices and that’s what we did from the word go.

Being back in a theatre:

I’m really looking forward to returning to theatre and it being safe to do so. Like so many people, I’ve missed that feeling of being part of a live event and it is so reassuring to see theatres reopening and venues putting so much thought and care into how to keep audiences secure.

Role of the arts coming out of pandemic:

The experience of the last year has really taken the toll on our mental health as the separation from community has left so many people feeling extremely lonely. I think the arts have a key role to play in bringing people back together and reducing that sense of isolation.

Advice to young artists:

. I would say, follow your instincts, be true to yourself and follow your intuition. Be brave, be challenging and don’tfollow anyone else’s mantra. Don’t be confined by the politics of the time; be true to yourself, whatever that self is, and make work from the centre of who you are.

PLEASE SUPPORT US FOR JUST £2 A MONTH