The government’s public sector pensions bill is being debated, with much nonsense being spouted from the government benches, and some great sense by Labour MP John McDonnell. So in his honour and to counteract the Tory tripe, I’m reposting my article on public sector pensions that I wrote back in May – one of my earliest posts:

News this week that set me thinking: the government ran at a surplus of over £16 billion in April – thanks to it taking on the Royal Mail pension scheme. This action put the pension scheme assets of about £28 billion into the public balance sheet, giving a big, one-off boost to the public finances. The significance of this doesn’t seem to have drawn much attention in the media.

Apparently, this move also meant taking on a projected liability in the scheme of £37 billion, but the government was happy to take the immediate positive hit in spite of the supposed deficit. If you think this poses a big question as to why they would do this, when their expressed aim is to eliminate the deficit, you’d be absolutely right.

They say that actions speak louder than words. Since it came to power, the coalition government has waged a constant propaganda campaign to convince the public at large that the country can’t afford to continue its current public-sector pension schemes. Words and phrases like ‘unaffordable’, ‘gold-plated’, ‘unsustainable’, ‘untenable’ are bandied at every opportunity, the clear aim being to convince the public that unions who resist the changes are being unreasonable, greedy, unrealistic – and to try to ensure that when industrial action is taken (which is really the only weapon that unions can wield), they do not have public sympathy. And largely, this tactic has worked – ask the average person whether public sector pensions are sustainable without reform, and if they’re not employed in the sector themselves, or a close relative of someone who is, they’ll answer an emphatic ‘no’.

And yet, and yet…

Here we have a government that uses all the above terms with abandon in its propaganda war – yet when it is taking on an additional supposed net liability, what does it do? Does it ring-fence the £28bn to offset against the ‘huge’ liability and reduce the burden on the long-term public finances? No. It banks the money like a shot to offset against the deficit of a single month, and proposes to sell off this surplus, which, by definition, it will have to do for less than its face value. (see https://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/budget/9158721/Budget-2012-28bn-of-Royal-Mail-pension-assets-to-pay-down-national-debt.html)

You see, this is what governments do with surplus pension funds when they’re available – they put them into the general coffers and use them for whatever they feel like. Much is made by the coalition, and by their friends in the right-wing media, of the idea that most public-sector pension schemes are ‘unfunded’. The Royal Mail scheme has been a funded one – members’ contributions are put into a ‘pot’, which is then invested, hopefully grows, and the funds sit there ready to pay out when members retire and need to start drawing a pension.

An ‘unfunded’ scheme is one where the cost of current pensioners is covered by the contributions of those who are still working – who in turn rely on subsequent generations to pay in to cover their costs. But the decision as to how contributions would be handled wasn’t made by the workers or their unions. It was taken by the government that set up the schemes – who knew that, in earlier days when people didn’t live so long, there would be substantial surplus contributions that they could spend on other things. In effect, these funds were set up in such a way that they would act as an additional tax on public-sector workers, who would make a net contribution to the finances of the country.

Governments of all stripes have profited from this arrangement for decades. Teachers’ pension contributions, measured across the lifetime of their pension scheme since it was set up, exceed what has been drawn to pay retired teachers’ pensions by £46 billion (see www.teachers.org.uk/node/14349). But those funds didn’t go into a ‘pot’ to cover eventual pension liabilities. They went into the public purse and benefited the country as a whole – public and private sector workers alike. The government hasn’t had to dip into a fund and acquire this lump sum like it has with the Royal Mail fund – it’s taken this money in a continuous stream since the scheme was set up.

Likewise, NHS workers’ and local government workers’ schemes have been making a contribution of billions of pounds into the treasury every year – and continue to do so. Yet the government is trying to impose higher contributions and a longer working life on workers in these sectors (while at the same time freezing wages), on the basis that – projected far into the future – the schemes are ‘unsustainable’. Is that true?

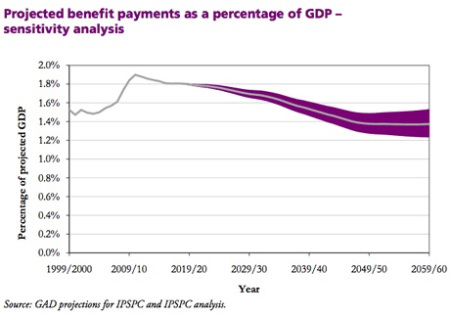

In short: no. The graph above was published by Lord Hutton – yes, the same Lord Hutton whose report the government is using to justify the structural changes to public sector pensions. The graph shows the projected cost of pensions as a percentage of GDP out as far as 2060. As you can see, the cost of pensions relative to GDP, even in the worst-case scenario represented by the upper-edge of the purple band, is lower than the cost now. Now here’s the real kicker – the figures used to create the graph are based on an unchanged pension structure.

Yes, you read that correctly. Without making any changes to pension contributions, without switching to a career-average calculation instead of a final salary one, and without making public-sector workers work longer, the cost of pensions relative to national income is going to go down. (see https://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/reality-check-with-polly-curtis/2011/nov/28/pensions-public-sector-pensions, a bit more than 1/3 of the way down the page).

Now, even unions admit (same link as just above) that if you look at all public sector pensions as a whole, there is currently a deficit of approx. £4 billion per year. Looks bad, doesn’t it? Especially if you choose to forget that these same funds have been putting money into the treasury for decades. But what does that really mean? The right-wing Telegraph said about the £9 billion theoretical deficit that it was equal to about £365 for every household in the country. On that basis, a deficit of £4 billion (I’m excluding the Royal Mail £9bn because the government is choosing to take on that debt, and the £9bn is not per year – it’s across the lifetime of the liabilities of the scheme) for public sector pensions equates to £162 per household per year.

That might sound like a lot. But as with anything, how big something looks depends on your perspective. And taxing households is far from the only way of generating revenue to cover any pension deficit.

As reported by various newspapers (for example here: https://www.guardian.co.uk/money/2011/dec/06/hmrc-tax-deal-vodafone), HMRC made a ‘deal’ with Vodafone to let them off a tax debt of around £7 billion. This debt was accumulated over a few years, but even so, simply taxing Vodafone properly would have covered a major part of the annual pension cost. Tax even 3 or 4 companies properly and the cost is more than covered – and in an eminently sustainable way.

Or try another angle of view. The cost to the treasury, every year, of giving tax relief on pension contributions to the richest 1% in this country (yes, the same 1% who became £155 billion richer according to the Times Rich List!) was around £10 billion(www.guardian.co.uk/politics/reality-check-with-polly-curtis/2011/nov/28/pensions-public-sector-pensions again). It would be easy to change the tax relief laws for the pension contributions of the super-rich and more than cover the pension costs of our hard-working public-sector workers, whose pension contributions have been boosting the public finances for generations.

So, even leaving aside considerations that we as a country owe it to our public workers, in pure financial terms, to provide them with the pensions that were promised to them when they took the jobs, this government has a number of alternatives to fund any ‘pension gap’ without taking money out of public workers’ pockets (which depresses the economy to boot!). They just don’t have the sense to use them – and prefer to pursue an ideological aim, disguised as something else. Yet again.

This government has plenty of ‘form’ for this kind of behaviour. We should know better than to believe them. We do know better.

And you know what? If the worst comes to the worst and it takes a slightly bigger slice of my tax contribution to fund a fair, decent pension scheme that should be a source of pride to our country rather than a target for attack – well, I’m cool with that.