(Apart from the USA, where their constitution forbids it).

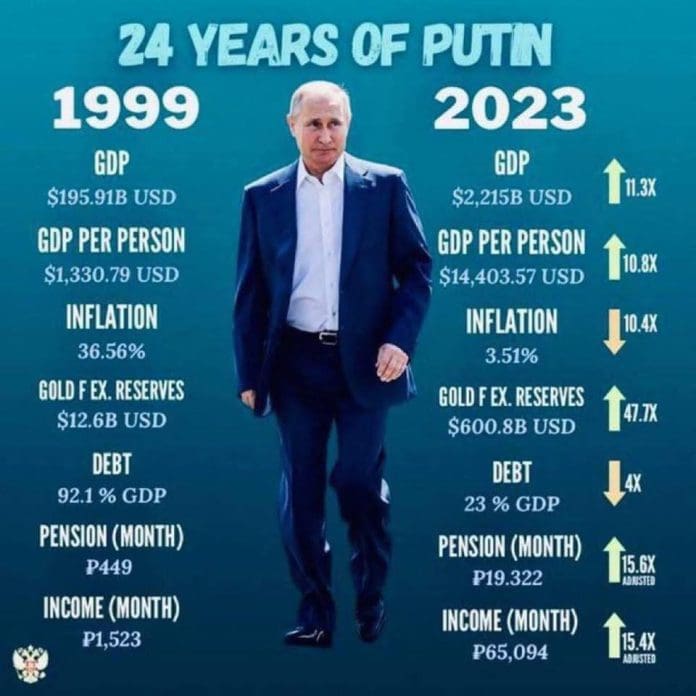

The following provides an analysis of the economic growth from when Putin arrived in the Kremlin. It avoids detailing the corruption, primarily because every economy is riddled with political and corporate corruption, most of which is ignored by the Western corporate media. It also largely avoids the impact of the war with Ukraine, as it is too early to ascertain objective data as to the consequences.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and GDP Per Person

In 1999, Russia’s GDP was a modest $195.91 billion USD. By 2023, it had increased more than elevenfold, reaching approximately $2.2 trillion USD. This growth was largely underpinned by soaring global oil and gas prices, Russia’s principal exports, particularly during the early 2000s.

Similarly, GDP per capita rose from around $1,330 USD in 1999 to roughly $14,400 USD in 2023, a more than tenfold increase. These numbers reflect genuine progress in national income and development. Urban infrastructure improved, poverty levels declined, and for a time, the middle class expanded.

However, both indicators are heavily reliant on commodity prices and do not capture inequalities in wealth distribution or regional disparities. Incomes and investment remained concentrated in major cities, while much of the country saw slower improvements.

Inflation and Monetary Stability

In the late 1990s, inflation in Russia was alarmingly high, sitting at 36.5% in 1999. The rouble had experienced a dramatic devaluation, and public confidence in the currency was low.

Under Putin, inflation was gradually tamed, reaching 3.5% by 2023. This stability was largely due to prudent policies by the Central Bank of Russia, including inflation targeting, interest rate hikes, and the accumulation of reserves. These measures contributed to monetary confidence and stabilised prices across the country.

While brief inflationary spikes occurred, most notably after the 2014 Crimea annexation and the 2022 Ukraine invasion, authorities managed to bring inflation under control, reflecting improved macroeconomic management.

Gold and Foreign Exchange Reserves

In 1999, Russia’s gold and foreign exchange reserves were a meagre $12.6 billion USD. By 2023, these had ballooned to approximately $600.8 billion USD, a nearly 48-fold increase.

This stockpile was part of a long-term strategy to reduce external vulnerability and ensure financial sovereignty. The reserves served as a buffer against sanctions, currency volatility, and capital flight. Notably, Russia’s emphasis on gold (as opposed to foreign currency holdings) increased after 2014, as geopolitical tensions with the West intensified.

However, the efficacy of these reserves was called into question in 2022, when Western nations froze a substantial portion of Russia’s foreign-held assets. The move exposed the limitations of financial autonomy in an interconnected global system.

Public Debt

In 1999, Russia’s public debt stood at a staggering 92.1% of GDP, reflecting years of borrowing and mismanagement. By 2023, this figure had fallen dramatically to 23% of GDP, positioning Russia as one of the least indebted major economies.

This fiscal conservatism allowed the Kremlin to maintain economic stability during crises. Nevertheless, ‘critics’ argue that such frugality often came at the cost of underinvestment in healthcare, education, and infrastructure, sectors critical for long-term development and social equity.

Pensions and Monthly Income

The average monthly pension in 1999 was ₽449, rising to around ₽19,322 by 2023, an over 15-fold increase. Likewise, average monthly income increased from ₽1,523 to approximately ₽65,094 during the same period.

These figures suggest significant improvement in material living standards. However, real wage growth stagnated after 2014, and inflation eroded purchasing power for many citizens. Pensioners, in particular, remained vulnerable, especially as the government raised the retirement age and reduced subsidies to manage costs.

Income growth was also highly uneven. While urban professionals benefited from higher wages, workers in rural or industrial regions often saw minimal real gains.

Household Savings

Russian households saw an improvement in their ability to save during the 2000s, aided by wage growth and greater economic stability. However, average savings rates remained relatively modest, estimated at 10–12% of income, and were highly unequal across income groups.

For many Russians, particularly outside major urban centres, saving remains a challenge. Economic shocks, such as Western sanctions and global recessions, forced households to dip into their reserves. In recent years, surveys have shown that a significant proportion of the population would struggle to cover unexpected expenses, revealing a fragile safety net.

A Dual Legacy

Vladimir Putin’s economic legacy is one of contrasts. On paper, the numbers are striking: GDP has surged, inflation is low, reserves are strong, and debt is minimal. These achievements highlight the state’s ability to ensure macroeconomic stability, particularly in turbulent times.

Yet, Russia’s economy remains fundamentally dependent on oil and gas exports, vulnerable to geopolitical isolation, and hampered by demographic decline and limited innovation. Income inequality, underdeveloped institutions, and restricted civil liberties further hinder broad-based, sustainable growth.

Ultimately, Putin’s economic record is one of early success followed by strategic rigidity. The Russian economy has proven resilient, but its long-term trajectory remains uncertain, particularly in the face of growing international isolation and domestic discontent.

Many Western politicians look on in awe at Putin’s achievements. Many even feel threatened and dedicate much of their political lives to seeking to undermine them. We must take many of their criticisms with a pinch of salt. We should look at the data and make our own sense of it.