The legacy of colonialism has ensured racism and the environmental emergency are inextricably linked. A new report by the Runnymede Trust and Greenpeace explores the impact of this discrimination and provides a rallying call for environmental justice.

As you read these words, think about the air you’re breathing. Is it fresh and clean, or have nearby roads and industry mixed dangerous pollution into each breath? Think about your wider neighbourhood. Is there good green space nearby? How easy would it be for you to get to a beach, a mountain or a lake?

On average, if you’re a person of colour in the UK, your answers were likely very different to the average white person. That’s because people of colour in Britain are more likely to live close to a waste incinerator. Black people in London are more likely to breathe illegal levels of air pollution than white and Asian groups. And Black people living in England are nearly four times more likely than white people to have no access to outdoor space at home, whether it’s a garden or a balcony.

Of course, everyone suffers from environmental damage, and the most deprived people, of all backgrounds, deal with more than their fair share of it. But even taking poverty into account, it’s people of colour who are often hit hardest. But this isn’t widely understood.

The awareness gap

A recent YouGov survey shows that these environmental inequalities are hard to see for the vast majority of the UK public, most of whom won’t experience them first hand. Over a third (35%) of those surveyed believe that people of colour and white people in the UK are just as likely to live close to a waste incinerator, with just 12% believing communities of colour are more likely to have one in their area. More than half of respondents (55%) believe there’s no difference in exposure to air pollution between white people and people of colour in London, with just 16% believing that BAME communities are worse affected. And when it comes to access to green and outdoor spaces, about half of the public (47%) believes there are no significant differences between ethnic groups, against just 26% who think people of colour enjoy less access.

Right now, the public isn’t just missing the realities of the present. It’s misunderstanding the inheritance of the past. We can’t understand the environmental crisis, or address its root causes, without understanding the racism that it has sprouted from, and how it still maintains it today.

Most people don’t think of themselves as being racist, and try their best to treat everyone equally. But these individual good intentions are set against a world that, in a million large and small ways, has been built around valuing some human lives and experiences over others. Over the centuries, this logic has crept into our laws, our culture, the layout of our cities, and the deepest parts of our minds, steadily building up over time like silt in a river. This has affected every aspect of daily life, and the environment is no exception. This is what systemic racism is.

This is also where understanding the links between race and class becomes crucial. People of colour in the UK are more likely to live in poverty than their white counterparts and are also more likely to live in economically deprived, urban areas. The UK’s most deprived areas suffer most from environmental harms, and people of colour in those areas are likely to suffer. Of course, economic deprivation is both a tool and a consequence of racism, so it’s impossible to separate class issues from race issues.

Audrey Siegl, a Musqueam woman from British Columbia, Canada, and renowned public speaker, drummer and singer, stands in a small Greenpeace boat defiantly signalling Shell’s drilling rig to stop. The oil rig was on its way to the Alaskan Arctic in 2015 when it was confronted by Audrey, who was one of six people from six First Nations onboard Greenpeace ship MY Esperanza, as part of a global movement of seven million people calling for Arctic protection. Just three months later, Shell announced that it would cease oil exploration in the Alaskan Arctic. © Greenpeace / Keri Coles

Confronting injustice

For decades, Indigenous Peoples, people of colour and their allies have been fighting environmental racism, and highlighting its many injustices. Today, a new report from Greenpeace and the Runnymede Trust gathers these stories and struggles together. It should be a rallying point for those already working on racial justice issues, and a call for the wider environmental movement to join them.

The report cites examples of environmental racism from all over the world, but they all connect back to the UK. It’s crucial to understand our country’s central role in these injustices. The UK is the birthplace of the industrial revolution, a global financial hub, and an imperial power that has invaded or colonised practically every country on earth. This ubiquity has left our fingerprints on all the overlapping crises of our age, and gives us a special responsibility for how they play out. The centuries of exploitation and discrimination is behind the environmental inequalities that split our world apart today.

People of colour across the globe are disproportionately losing their lives and livelihoods as a result of the environmental emergency. These impacts fall heaviest on those who did the least to cause them and have the least resources to be able to cope with it. Much of the carbon from fossil fuels in the atmosphere today came from Europe, the US and other wealthy countries in the global north, yet nearly all the countries most impacted by the climate crisis are in the global South.

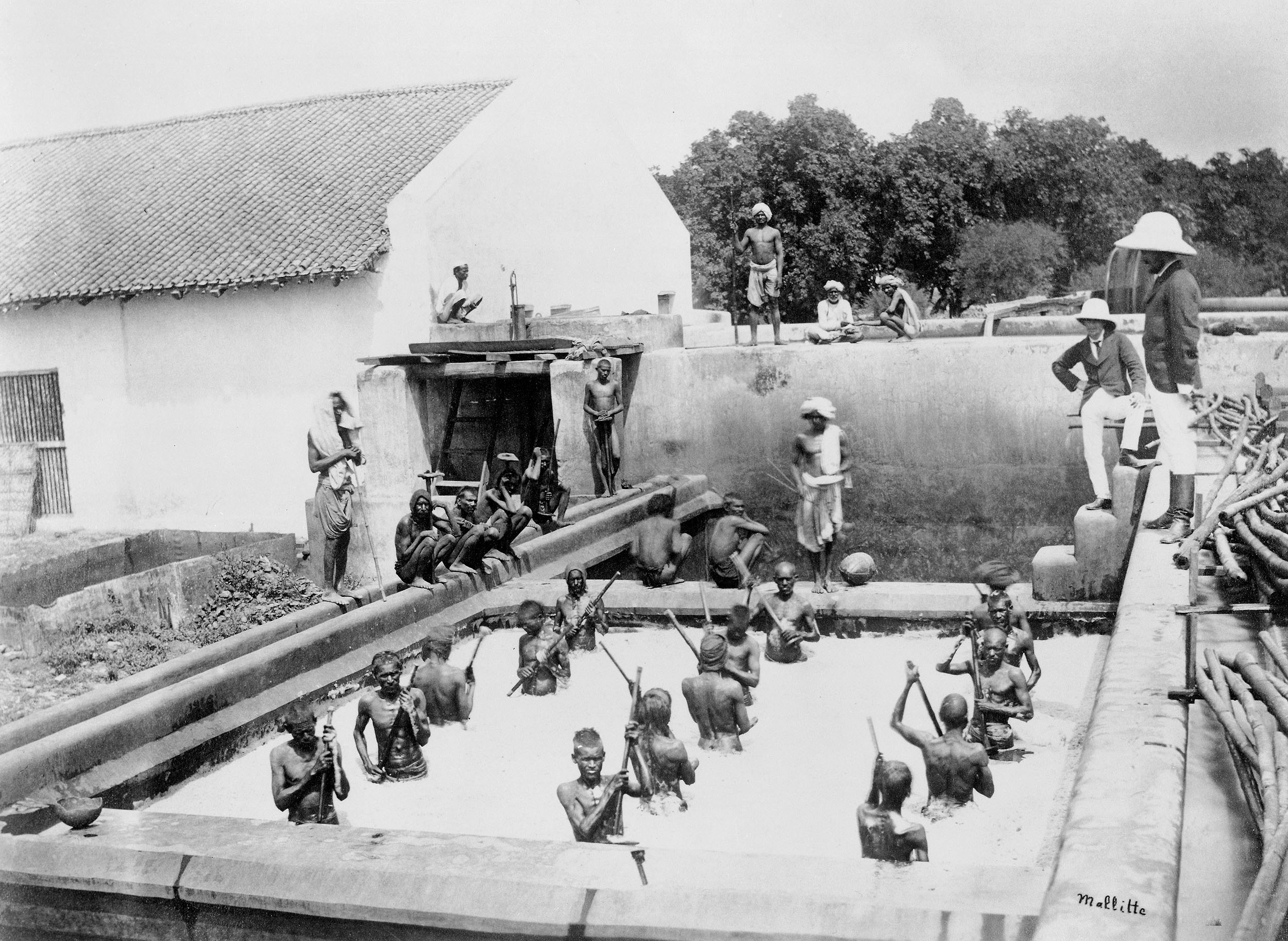

Beating an indigo vat by hand, Allahabad, India, 1877, by French photographer Oscar Mallitte. In the early 19th century, British colonisers exploited people, land and resources, establishing indigo plantations across India to farm and process this highly profitable crop. The demand for the blue dye in Europe gave it a status similar to commodities like tea, coffee, silk, and gold. © SSPL/Getty Images

The long legacy of colonialism

These injustices, and the exploitative relationships that underpin them, are the legacy of colonialism. The British empire, and the corporations it sponsored, raked in enormous riches from slavery, cheap labour and the plunder of raw materials worth trillions of dollars. Thanks to technological advantages and colonial oppression, rich countries have squeezed huge profits out of the fossil fuel economy while setting the globe on a path of dependence on fossil fuels and causing much of the associated emissions, leaving the global South poorer and more exposed to the environmental emergency as a result.

The treatment of entire groups of people as inferior or less deserving of a decent life is still allowing governments and industry to dump environmental impacts on to the global South. Since the heaviest impacts of the climate crisis fall onto poorer, less powerful countries, fossil fuel giants and governments in the global North feel less pressure to get to grips with the problem. Since the UK’s plastic waste is shipped off to some of these same countries, the plastic industry and our government can get away with not tackling our plastic problem at the source. And since it’s mostly Indigenous peoples and local in the global South that suffer from the destruction of the world’s rainforests to produce palm oil, meat or timber, companies and governments can carry on chopping down this climate-critical ecosystems with near impunity.

Fridays for the future MAPA (Most Affected People and Areas) activists, calling on the UK Government and world leaders to stop failing us on the climate crisis, outside the 26th UN Climate Change Conference, (COP26), in Glasgow, UK, November 2021. Activists (from left) are Farzana Faruck (Bangladesh), Maria Reyes (Mexico) Jakapita Faith Kandanda (Namibia), Edwin Moses Namakanga (Uganda). Their placards read “Pay your climate debt”, “Climate reparations”, “Denial is not a policy!” and “You can’t cheat nature”. © Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert / Greenpeace

The action we demand

As it will be clear by now, these are huge and complex issues. There’s no single magic bullet that will solve them all at one stroke. But recognising these inequalities and where they come from has to be the first step towards putting them right.

These are some of the things that need to happen if we are to tackle the fundamental injustice at the heart of the nature and climate crisis:

- Those most responsible for the environmental emergency must be held accountable and pay their fair share of the loss and damage. Immediately, this means that global North countries must pay their fair share of financial assistance to account for the losses and damages imposed on poorer nations in the global South as well as support for adaptation. The next major climate summit – the COP27 hosted by Egypt – will be the key moment to make this happen.

- When it comes to money, technology and political power, centuries of exploitation have tilted the global playing field against poorer countries in the South of the world. This is why shifting power and resources back to these countries is absolutely key to tackling environmental injustice. Practical ways to achieve this include debt cancellation, reforms to international institutions, taxation that makes polluters pay, enactment of land-rights and the patent-free sharing of green technologies with the global South.

- We need to move away from a wasteful economy that treats people and nature like resources to be mined for profit to one that’s grounded in restoring nature and allowing people to thrive. Space for new thinking is needed around alternative ideas to promote progress that is based on the collective well-being of both humans and nature. A just transition away from the unfair, extractive economy that dominates our society will not just tackle the impacts of the environmental emergency but will also start to address the hugely disproportionate injustices facing low income communities and people of colour.

The fight for the environment is a fight for equality and justice. And the simple truth is that environmentalism that excludes people of colour and other marginalised groups can never win. It will miss out on a wealth of knowledge – modern and traditional – on how people can live well with nature. But just as importantly, it will miss out on the energy of those with the biggest stake in its success. The environment connects to everything. It’s time environmentalism did too.

Find out more about Dr Mya-Rose Craig on Birdgirl.

If you prefer demanding content that turns the apple cart upside down please SUBSCRIBE to our Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQ1Ll1ylCg8U19AhNl-NoTg

and please support us where you can: Award Winning Independent Citizen Media Needs Your Help. PLEASE SUPPORT US FOR JUST £2 A MONTH https://dorseteye.com/donate/