Well…that’s yet another year year done and dusted.

My old Mum always used to say the older you get, the faster they go, and true to her oh so wise (but often infuriating) words, the older I’m getting, the faster they’re bloody well going.

In fact they’ve now almost hit warp speed!

New Year’s Eve is upon us and tonight for some, it’ll be a time of feasting, fun and frivolity, maybe a drop of drinking and dancing, hopefully joy for those undisclosed delights to yet come and a few shed tears for those we’ve sadly left behind.

Don’t make the mistake though of thinking that your Victorian ancestors were all straight-laced and poe faced when it came to New Year’s celebrations.

Religion and charity might have played a big role in their lives, but they certainly knew how to party too when push came to shove, as my last years blog on this festive night shows only too well

https://susanhogben.wordpress.com/2014/12/31/7454/

Well, this year I’m on a slightly different tack, grabbing at small snippets of New Years Eve news from different years.

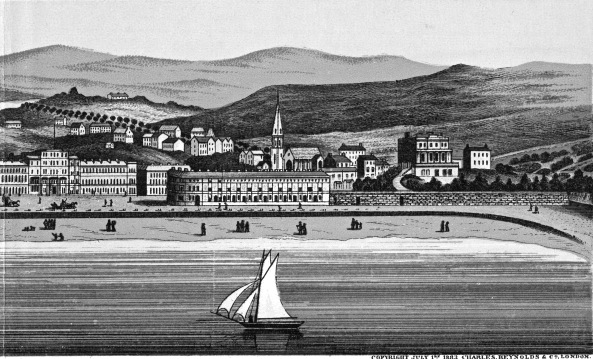

There were some fractions of Weymouth’s population who didn’t need the excuse of New Years Eve to create mayhem and mischief.

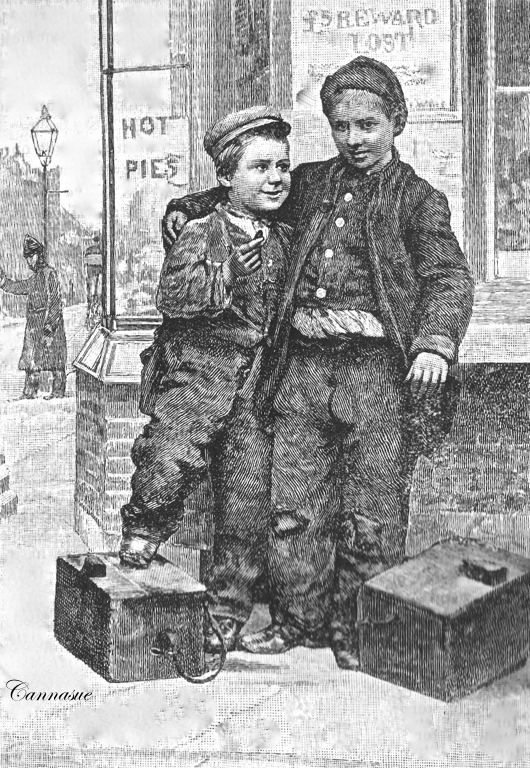

Come 31st December 1864 and a certain “Market House Arab” was causing the sellers problems in the town’s market hall.

There was no shutting up shop at 5.30 in those days, traders traded well into the night, even on such a night. (Might well have had something to do with the tradition of making sure you had money in your pocket on the first day of the New Year, for if you didn’t it foretold a year of poverty and misery.)

Fourteen-year-old Henry Charles and his pesky pals had “infested the market-house” with their high jinks, the police superintendent declared that “the boys were annoying everyone who passed by or through the market-house.” He even declared that things had got so bad that “unless something was done in the matter he feared the market-house would have to be closed.”

On that particular evening Henry and his cunning crew had entered the market on the pretense of buying some apples, but they were fully intent on making mischief whilst there.

Henry suddenly snatched up a massive turnip from the nearby veg stall and launched it at a passing “poor dog,” but missed it by a mile.

Instead, the offending turnip landed with an almighty thump on the toes of an unsuspecting passing Mr Crocker.

For his sins Henry Charles’s night of revelry was brought to an abrupt end, as the Weymouth church bells rang the New Year in, he was stuck behind prison bars.

(Here’s hoping that the old Victorian superstition that what ever you were doing at midnight would be a fore runner to your years fortunes didn’t come true.)

The same column that revealed Charles’s misdemeanors also gave us a glimpse into the world of Weymouth’s maritime history.

On the 31st December the returns for the UK’s Pilots were issued.

Weymouth and Portland of 1863 could boast a total 11 licensed pilots who worked from the bustling quaysides, their job was to bring in or escort out vessels from the working ports of both Weymouth and Portland Roads.

Each man had to pay a princely sum of two guineas for his license and 6d in the pound for any monies earnt.

Their vessels flew a distinctive white and red flag to identify to incoming vessels that they were licensed to board them and provide safe passage should they need it.

The Lookout for the Weymouth men was up on the Nothe.

It was their regular haunt, where in the summer they’d lie out on the grassy bank, squinting eyes firmly fixed on the horizon, or come bad weather, shelter inside a wooden hut created from an old boat, looking glass to eager eye, waiting and watching for any approaching vessels coming into view.

For those eleven men of the local waters, knowledge was everything, tides, drifts, sandbanks and currents.

They might have only been working around the shores of our relatively sheltered and safe bay, but their life could often be very dangerous.

Something William Smith aged 48 knew only too well.

Married to Susan and living with their family along Cove Row, at no 5, it would not have been unusual for William to return home bearing the marks of someone else’s fists or impression of their boots.

Such was the case in January of 1867 when he had tried to board an incoming Italian brig, he was viciously set upon by the crewmen and sent packing with more than just a flea in his ear.

Just around the corner from William, at no 9 Hope Quay, lived 46-year-old Edward Tizard and his wife Bathsheba and their family.

These pilots often found themselves not only facing personal conflict when trying to do their jobs, but frequently had to contend with conflict in the courts also, when disputes were fought over fees, or the right to board vessels.

Something which could become a bit of a minefield considering many who sailed into our waters spoke no English at all, and all the hand gestures in the world could not convey monetary transactions, or so they claimed afterwards.

Pilot John Perks aged 42 lived in Hope Street, he too was a family man, along with his wife Mary Ann and their veritable brood.

His story shows how precarious a life could be for those plying our shores for their trade.

In 1857 John had almost lost his life along with two other pilots, the tale of which I told in ‘Maritime Mishaps and Mayhem of 1857.

Come 1862, and work was hard to come by, trade was slow for the local pilots. In desperation John had set to sea in his vessel, the Eliza, along with his crew. They had been at sea for two days and a night, frantically looking for any sign of sails of approaching vessels to their port, hoping to catch any trade before his competitors.

So exhausted did they become that they all eventually fell into a deep sleep, at which point the drifting boat grounded herself out on the dangerous Weymouth sands.

Having lost both anchors and seriously damaged her hull, poor old John and his crew faced the indignity of being rescued by his fellow pilots and local coastguards.

A plea was then placed in the local papers for donations to help “As Perks is a poor man with a large family, a subscription has been made by several gentlemen to enable him to repair his boat and pursue his usual avocations.”

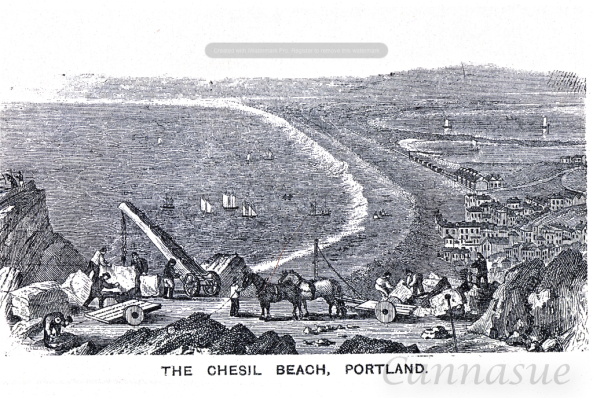

Fellow pilot, Thomas Way, was a true blue Portlander, at the age of 44 Thomas, his wife Isabela along with their brood lived in the little village of Chiswell tucked in just behind the mighty Chesil beach, .

Thomas supplemented his sometimes paltry and intermittent income by labouring on the Breakwater, money was hard earnt and an income from any means vital to keep kith and kin together.

The previous year had seen Thomas giving evidence in court about the tragic death of one of his fellow Portlanders, 36-year-old fisherman, Richard Attwooll.

One cold, squally Wednesday morning in November, Richard and a friend, William Lano, had gone out in their boat, they were fishing near the relative safety of the new Breakwater.

A sudden squall hit their vessel sideways and with the swell, thrust it up onto a metal pipe sticking out of the Breakwater structure.

The boat tipped,,,launching both men into the freezing rough waters.

Richard clung desperately to the pipe, but the constant pounding of the waves was dragging him down.

His precious hold was slowly loosening until at last his frozen fingers let go, unable to swim.

Richard’s head simply sank below the waves.

His fellow fisherman William could swim, but even then it was hard going battling the choppy seas.

At last managed to grab hold of one of the piles, hanging on for dear life, waiting and praying that he could find the energy to haul himself out onto the stones.

Thomas Way had been at work on the Breakwater that day and witnessed the disaster unfolding before him.

Unable to help either man all he could do was to help search for the body of Richard Attwooll when old Neptune decided he had no more use for it.

In fact it was only a quarter of an hour later that his mortal remains were thrown up onto the rocks, where Thomas came across him.

According to Thomas’s testimony, Richard’s hands were still warm to the touch, but there were no other signs of life.

For finding the body, Thomas Way was awarded the customary 5s fee, but like most close knit sea-faring communities, without hesitation, he handed it over to Richard’s grieving widow.

Thomas wasn’t the only pilot in the Way family, so too was his younger brother Edward. Also like his brother, Edward and his brood lived in Chiswell.

Though these men were highly experienced mariners and used to any amount of high seas and storms that nature could throw at them, even they weren’t immune to the immense damage she could wrought.

In the February of 1866 one the the Way’s pilot boats broke loose from her moorings during a fierce storm and ended up stranded up on the rocks of the breakwater.

There was nothing they could do but watch in dismay, once the tide receded the pounding waves literally smashed their boat to nothing more than mere matchsticks.

William Smith was one of the longest working pilots in the port, he also owned one of the larger cutters working as a pilots ship, the Palestine.

But that’s not surprising really because he also traded as a ships broker. The Smith family were another one of the mariners group who lived close together in this harbourside area of Hope Square.

So too did pilot Edward Chaddock and his burgeoning family, as part of this tight knit community, just along Cove Row, and fellow pilot, 44-year-old William Grant lived just around the corner on Hope Quay.

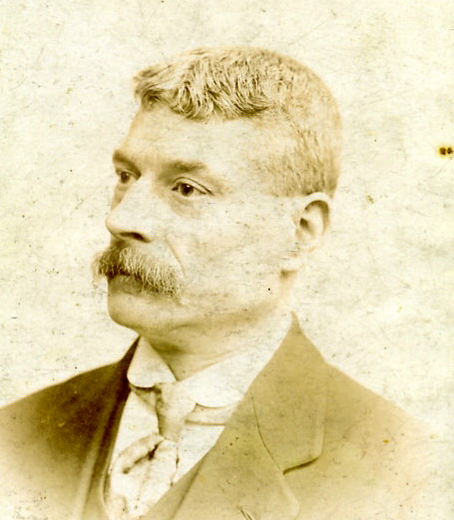

George Pulsford, (pictured below from an Ancestry public tree,) at 47, was one of the older men working the pilot boats, he was born, and along with his family, still lived in Lyme Regis, just along the coast.

I guess even in those days it was often a case of commuting to work, albeit via boat.

The final two qualified pilots plying their trade along our coastline that year were 33-year-old William Hallett, another Lyme Regis man and 39-year-old Thomas Beale.

Next in our New Years Eve tales, we come to a slightly more traditional and heart warming event.

The year 1872, a year which had been a year full of memorable events. It was the wettest one on record…ever!

(Not matched again until 2012.)

It’s the year when the very first FA Cup final was played at the Oval, and a meteorite suddenly emerged from out of space and struck the Earth.

Closer to home, the Royal Adelaide sank off Chesil beach with the loss of 7 lives…

…and Great Britain celebrated the completion of the Portland Breakwater.

For the poor of Weymouth, at least their New Year’s Eve was going to be heralded in with a jolly good feast…that is, for those who could claim to be over the age of 60, and I bet a few might well have added on a year or two to their age for the occasion.

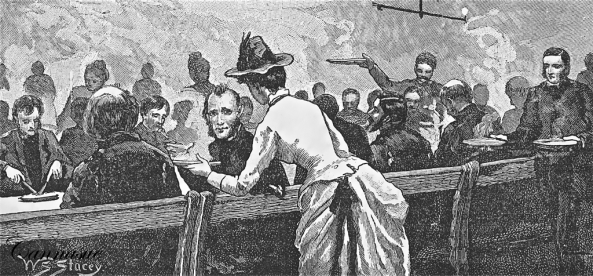

Nigh on 200 Victorian Weymouth and Melcombe Regis OAP’s found themselves being seated and served by a bevvy of local bigwigs, their friends and families.

What was their festive feast ? “an excellent dinner of beef and pudding,” all washed down with a “supply of good beer” courtesy of Messrs Devenish & Co.

Amongst the feasting crowd that night was 91-year-old John Atkins, a retired mariner who resided at no 18 Petticoat Lane (present day St Alban Street,) along with his 50-year-old son Samuel and family.

Presiding over the proceedings was the town Mayor, Mr J Robertson, his first deed of the night was to wield his knives and carve the first of many turkeys.

After dinner was done and dusted and the last dram drunk, the Mayor then “suitable and affectionately addressed the assembly.”

Not only did he ordain to magnanimously shower them with words of good tidings and kindness but on their way out they were “presented with 6d each.”

None of this would have been possible without the organisation, hard work and persistent cajoling of the town’s wealthier patrons purses by one William Thomas Page, the man whose job it was to collect the poor rates and later sat on the board of Guardians of the Weymouth Union or workhouse.

And finally, it was good news for some to start their new year.

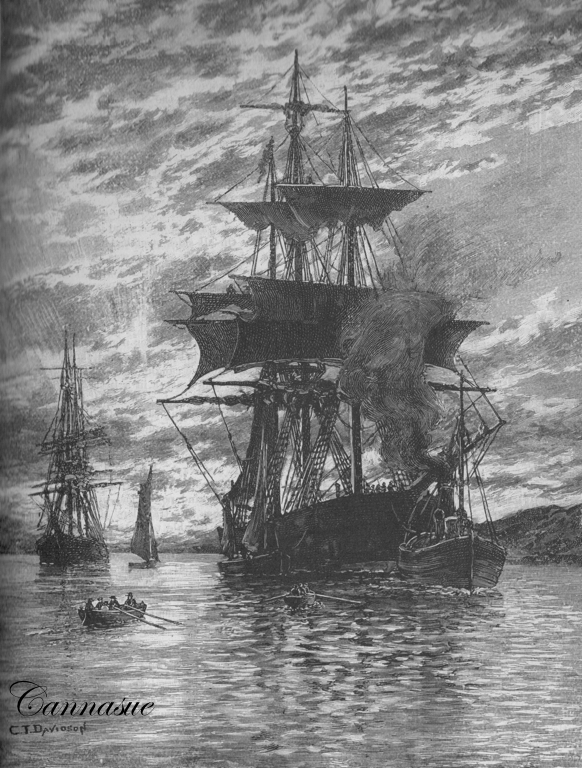

Early on first morn of the New Year of 1862 saw a vessel arrive in Weymouth port, for one group of sea faring men it meant their new year was heralded in with great cheer and much rubbing of hands with glee.

On the eve of the years changing, a ghost ship was found mysteriously drifting on the tide out in the bay.

Not a single soul to be found on board, but what terrible misfortune could have possibly befallen her crew?

Was this some form of witchery that could make men vanish into thin air, or an attack by mysterious vengeful sea creatures, luring the sailors into the depths with their soulful songs?

The ghost ship was the brig Lavonia, still fully laden with the coals that she had collected from Llanelly, Wales, all under command of the ship’s master Mr Huelin, a Jersey man.

They had set sail that fateful final day of of 1861, bound for Dieppe, when just after midnight, and having gone for some unknown reason somewhat off course, the vessel struck rocks off St Alban’s Head and here it became firmly grounded.

Inside the stricken boat the waters began rising fast, at which point, “fearing her sliding off the rock into deep water, the captain resolved on quitting her, and, leaving the wheel to the eccentic goddess Fortune, took to the boat, all landing safely at Kimmeridge Coastguard station.”

The Lavonia did indeed later slide off the rocks, but not into the deep as her captain had feared but to sail on out into the bay.

A little later that morning another coal vessel heading from the Welsh coast towards Dieppe came across her and brought her into port. The crew of the steamer Harp couldn’t have been more pleased with their lucrative salvage…it meant a jolly good start to their new year.

I hope you’ve enjoyed some of this years tales, maybe even met a few of your ancestors, learnt something of their lives in our own Victorian Weymouth and Portland.

Wishing you all a very Happy and Healthy New Year.

VICTORIAN TALES FROM WEYMOUTH AND PORTLAND