Astronomy in the summer months isn’t the most convenient of hobbies; largely because it doesn’t get properly dark ‘till gone midnight. It’s during these months though, that we’re able to see the Milky Way at its best. It stretches from Cassiopeia to the North down through Cygnus, where it seems to split in two at the Cygnus Rift, and from there down through Aquila and Scutum to Sagittarius and Scorpius in the South. With the Milky Way where it is at the moment (high overhead) we’re able to look ‘above’ and ‘below’ the flat plane of our galaxy, into what’s called the galactic halo (to the right and left of the Milky Way), It’s in this area, mainly grouped around the central core of the galaxy, that we tend to find globular clusters. Visible from late spring through to early autumn, we’re right in the middle of globular cluster season.

So what are globular clusters? Well, they’re groups of thousands of stars, gravitationally bound to one another in a relatively tight ‘ball’. No-one actually knows how they form, or why, but they do seem to be a natural and inevitable part of galaxy formation – most galaxies that have been observed have them. Ours has in excess of 200 globular clusters, the Andromeda galaxy more than 300. They’re some of the oldest objects in the galaxy, some almost as old as the galaxy itself.

Although it’s possible to see some globular clusters with the naked eye, perhaps using ‘averted vision’ – that’s where you don’t look directly at the object – you’d need a clear night and from a dark location. I’ve seen Messier 13 (M13),in the constellation of Hercules, one of the most famous globulars, from here in Cerne Abbas. A pair of binoculars will reveal a great many more of these clusters. They’ll appear as soft, fuzzy, spheres; clearly not stars (in that they won’t be sharp and sparkling). Viewed using a small telescope (such as a 4- to 5-inch reflector) they’ll appear larger again, with a grainy texture, and with some of the outer stars beginning to resolve into tiny but distinct points of light. A large telescope (such as a 10-inch reflector) will resolve stars to the core, and give the cluster the appearance of a sparkler.

Globular clusters, especially when viewed through a large scope, really are an awe-inspiring sight. M13, for example, has over 250,000 stars, M5 has been estimated as containing as many as 500,000!

As well as being visually impressive, globular clusters are pretty awe-inspiring when you get to know them, as it were. For example, M13 is25,100 light-years away from the Earth, and has a diameter of over 160 light years! M22, on the other hand is in the region of 10,600 light years away, is one of the brightest globulars in the night sky, and, with a diameter of around 100 light years, appears to the naked eye (should you be lucky enough to be able to view it, low down in the South at this time of year) to be almost as large as the full moon!

As Douglas Adams said in The Hitch-hikers Guide to the Galaxy, “Space is big. You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is.” I find globular clusters give a hint of this scale. They look so small and compact that it’s easy to assume that they’re as dense as they appear to us. Thousands of stars densely packed together, with little space in between. However, they’re not as dense as they appear; the average distance between stars at the core is actually around the diameter of our solar system. If we take the orbit of Pluto (4.4–7.4 billion km from the sun) that means we’re talking about stars in the core of a globular cluster being around 10-15 billion km apart! Globular clusters may look small and dense, but they’re actually very, very big!

What’s up?

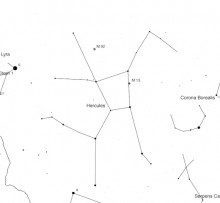

M13 is pretty much overhead at this time of year. To find it, look for four stars forming the corners of a trapezium. These are known as the ‘keystone’ of Hercules (they represent his torso), and the shape resembles the keystone you might find in a bridge or arch. Facing South, look directly up and you should see this overhead. Imagine a line extending from the lower right-hand star of the keystone to the upper right-hand star. M13 lies approximately two thirds of the way along this line (beginning at the lower star).

Hercules is home to another globular cluster: M92, one of the oldest in the galaxy. Imagine a line extending between the wider of the two stars in the keystone. One third of the way from the left-hand star, scan upward at a right angle to this line (by a distance approximately equal to the same length as that between the wider two keystone stars). Apps such as Google Sky Map (Android) or Star Walk (Android/iOS) on your smartphone, together with the image shown here, will help you locate these objects.

Clear skies!

Kevin Quinn is an amateur astronomer based in Cerne Abbas, he is the proud owner of a ten-inch reflector, a small refractor, and a hefty pair of binoculars. He tweets via @CerneAstro, blogs via theastroguy.wordpress.com, and his ebook ‘Demystifying Astronomy – A beginner’s guide to telescopes, eyepieces and accessories for visual astronomy’ is widely available.

©Kevin Quinn