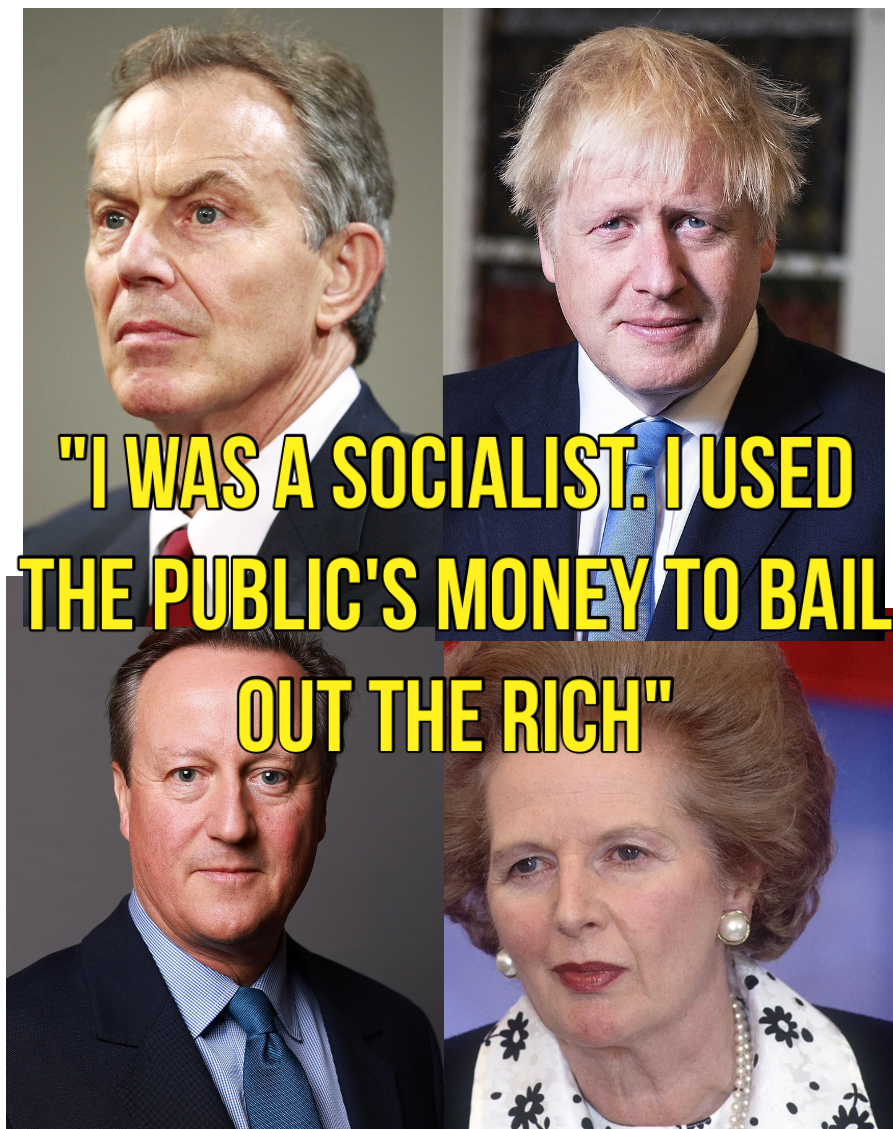

The following includes an expose of how the Labour Party have sought to get rid of any socialist or progressive who considers that the mass population should come first and have instead joined the neo liberal cartel using economic socialism to bail out the rich.

As former Shadow Cabinet member Chris Williamson asks: why stay in a party that only wants to purge you?

THOUGHT FOR TODAY

— Chris Williamson (@DerbyChrisW) November 6, 2024

Anyone who identifies as a socialist who's still clinging to the husk that was once the Labour Party should follow former Labour MP, @BethWinterCynon, out of the party. pic.twitter.com/f3v0NUlgDT

The Labour Party, one of the oldest and most influential political entities in the United Kingdom, has a storied history marked by ideological evolution, debate, and division. From its origins, Labour was a coalition of leftist factions, trade unionists, socialists, and moderate progressives united around the idea of improving the lives of working people. However, recent years have seen what many critics describe as a “purge” of socialists and left-leaning members within the party. This systematic removal of socialist elements reflects a tension at the core of Labour’s identity: a struggle between the party’s traditional left-wing roots and its modern aspirations for electoral viability in a political climate that often favours a manufactured ‘middle ground’. This phenomenon has intensified under recent leaderships, particularly that of Keir Starmer, leading many to question whether the Labour Party can still claim to represent the wide spectrum of left-wing thought that once characterised it.

Labour’s expulsion or suspension of socialists has been both overt and indirect, encompassing not only high-profile individuals but also a broader campaign to reshape the party’s ideological base. While expulsion, the most direct form of exclusion, has been reserved for select members, numerous socialists and activists within the party have been marginalised or discouraged through other methods, including restrictive rule changes, policy shifts, and stances on certain issues. The outcome is a Labour Party that, according to many socialists, no longer represents the aspirations and values that initially united the working class and the left. To understand the scope of this purge, it is essential to consider the ideological motivations driving it, the specific examples of how it has been implemented, and the impact it has had on the party’s internal dynamics and relationship with the electorate.

The ideological shift that underpins Labour’s purge of socialists is rooted in what is commonly described as a move towards the “centre-ground” of British politics. Since the days of Tony Blair and New Labour in the late 1990s, many within Labour have argued that the party must appeal to moderate voters, particularly in economically influential swing seats, when seeking to reclaim power. Blair’s tenure saw Labour moving away from its socialist roots to embrace a Third Way approach, which combined progressive social policies with market-friendly economics. This ideological pivot, however, triggered significant discontent among the party’s socialist factions, who felt that Labour was abandoning its core mission to oppose capitalism and promote democratic socialism. While Blair’s strategy brought three consecutive electoral victories, it also alienated large sections of the party’s traditional support base, particularly within the trade unions and grassroots activists.

The purging of socialists took on new urgency after the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, whose tenure from 2015 to 2020 reignited socialist ideas within Labour. Corbyn, a longstanding socialist and anti-austerity advocate, was popular among the party’s young members and activists, but his leadership faced severe resistance from the party establishment, who saw his politics as electorally toxic. During his leadership, Corbyn attempted to reorient the party towards its socialist principles, advocating for policies like renationalisation, expanded social services, and a more assertive stance against income inequality. His manifesto in the 2017 and 2019 elections highlighted these priorities, which drew a stark contrast with the ‘centrist’ ethos of previous Labour leaderships. Many ‘centrist’ MPs argued that Corbyn’s policies and style alienated moderate voters. They then set out to make this a self fulfilling prophecy, contributing to Labour’s resounding defeat in the 2019 general election. This loss became the justification for an accelerated shift away from Corbynite policies and personnel, setting the stage for a systematic attempt to root out socialist elements within the party.

When Keir Starmer succeeded Corbyn as Labour leader in April 2020, he campaigned on a platform of unity, promising to maintain key aspects of Corbyn’s policies while restoring discipline and electability to the party. However, his tenure has been marked by a series of actions that many view as a deliberate campaign to remove or marginalise socialists within Labour’s ranks. One of the most high-profile examples of this strategy was the suspension of Jeremy Corbyn himself in October 2020. Following a report by the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) into antisemitism within the Labour Party, Corbyn claimed that the scale of antisemitism in Labour had been overstated for political reasons. This led to his suspension, which, though later lifted, effectively sidelined him and alienated his supporters. Many socialists viewed Corbyn’s suspension as a clear signal that the party was no longer willing to tolerate vocal left-wing criticism or an alternative to Starmer’s ‘centrist’ approach.

Beyond Corbyn, other prominent socialists and left-leaning figures within Labour have also faced expulsion or marginalisation. For instance, figures associated with grassroots organisations like Momentum, a movement that was crucial in supporting Corbyn’s leadership, have seen their influence and representation within the party sharply curtailed. Numerous local constituency Labour Party (CLP) meetings and branches have been suspended or placed under investigation for supporting Corbyn or other left-wing figures, curtailing the power of local activists to influence party direction. In some cases, members have been suspended merely for expressing criticism of Starmer’s leadership or for passing motions of solidarity with Corbyn. This crackdown has extended to rank-and-file members as well, with many long-standing activists and socialists removed from the party or prevented from participating in decision-making processes.

Another example of the Labour Party’s purge of socialists is the expulsion of Ken Loach, the renowned socialist filmmaker and vocal critic of capitalism. In August 2021, Loach, who had been a member of the party for decades, was expelled on the grounds of his association with groups deemed incompatible with Labour’s aims. Loach was a high-profile supporter of Corbyn and an outspoken critic of Starmer’s leadership. His expulsion was widely condemned by socialists as evidence of Labour’s intolerance towards anyone advocating a transformative, anti-capitalist agenda. Loach himself described the move as part of a broader purge of socialists, stating that the party was “led by people who are trying to destroy the very heart of the Labour Party.” Many of Loach’s supporters argued that his expulsion marked a particularly draconian step, suggesting that the party was willing to expel even its most prominent and celebrated left-wing figures to consolidate control over its ideological direction.

Local councillors and activists have also faced removal or disciplinary action for perceived disloyalty to the party’s new direction. Socialist councillors, particularly those affiliated with left-wing organisations or who have expressed solidarity with Corbyn, have reported being deselected or blocked from running in local elections. For instance, in Liverpool, a city historically associated with left-wing politics, socialist councillors were prevented from standing for re-election, allegedly due to their criticism of Starmer’s leadership and policies. This practice of “reselection” has been seen by critics as a means to install candidates more aligned with the party’s centrist agenda, ensuring that local government structures also reflect the leadership’s priorities. These actions have alienated many within Labour’s grassroots, who see them as a betrayal of the party’s democratic principles and an erosion of local autonomy.

One of the more indirect but effective methods of marginalising socialists within Labour has been through procedural changes at the party conference and in policy-setting processes. Starmer’s leadership introduced rule changes that made it harder for left-wing members to influence policy and weakened the role of CLPs and trade unions in shaping the party’s agenda. For example, the rules around leadership challenges were tightened, raising the threshold of MP nominations required for a candidate to stand. This change was widely perceived as a way to prevent future left-wing leaders from gaining traction within the party. Additionally, rule changes around disciplinary procedures have centralised decision-making authority, giving the leadership greater control over who is admitted or expelled from the party. These procedural adjustments, while less visible than high-profile expulsions, have fundamentally altered Labour’s internal structure, limiting the power of grassroots members and socialist factions to participate in party governance.

The ideological consequences of Labour’s purge of socialists have had significant repercussions on its electoral strategy and public perception. By removing or sidelining socialist voices, Labour under Starmer attempted to appeal to disillusioned Conservative voters and recapture seats lost in the so-called “Red Wall” of traditional Labour strongholds. However, this strategy has drawn mixed reactions. Many of the party’s core supporters feel alienated by what they perceive as a betrayal of Labour’s founding principles. Critics argue that Labour’s move to the ‘centre’ risks making it indistinguishable from the Conservatives on many key issues, potentially undermining its appeal to progressive voters who are seeking a genuine alternative to neoliberal policies. Additionally, the perception of an ideological purge has eroded trust within Labour’s base, with many young voters and activists turning towards smaller, explicitly socialist parties or grassroots movements that align more closely with their values.

Supporters of Starmer’s approach argue that these actions are necessary to restore discipline and credibility to the Labour Party. They contend that the party’s shift away from socialism is a pragmatic move in response to the changing political landscape, where moderate voters and the media exert significant influence. According to this perspective, Labour’s electoral losses under Corbyn demonstrated the significant influence of the billionaire corporate media and how they much preferred a Starmer to a Corbyn. Starmer’s advocates claim that by positioning Labour as a moderate, reliable alternative to the Conservatives, the party can gain the support of ‘centrist’ voters who were disillusioned with the Conservative government’s handling of key issues like the economy and public services. However, this defence has done little to allay the concerns of socialists who see their purge from Labour as a repudiation of the party’s historical mission to represent the working class and advocate for systemic change.

The ongoing purge of socialists within the Labour Party underscores a deep-seated conflict between ideology and pragmatism. Labour’s leadership has opted for a path that prioritises electoral expedience over ideological purity, seeking to recast the party as capable of winning power in a divided country. This approach has brought electoral success but at what cost? It has alienated a large segment of the party’s traditional support base and sparking intense debate about what Labour stands for. We must remember that only 34% of those who voted chose Starmer’s Labour. For many socialists, the Labour Party’s purge of left-wing voices represents a decisive shift away from its roots, suggesting that Labour may no longer be the natural home for Britain’s socialist and anti-capitalist movements.

Therefore, the Labour Party’s purge of socialists reflects a complex struggle to redefine the party’s identity and purpose. Under the leadership of Keir Starmer, Labour has taken steps to marginalise or expel socialist members, a strategy justified by the desire to make the party more electorally viable. However, this campaign has alienated large sections of the party’s grassroots and has intensified ideological rifts that have simmered within Labour for decades. Whether this strategy will yield long-term success or further fragment Labour’s base remains uncertain. What is clear is that the Labour Party is that progressive voters no longer trust the Labour Party. They are increasingly looking for new homes as they realise that electoral success is now manufactured to suit the very wealthy and thus powerful. An increasing recognition is taking place that for those who desire a socialist/anti capitalist future, the ballot box is probably not the way forward.

The following are numerous examples of the taxpayer’s money being used to bail out the rich or to make the rich richer. Instead of the rich doing it themselves, which is how it is supposed to work, the public have to cough up when it all goes belly up.

International Bail-Outs Of The Rich

1. 2008 Financial Crisis Bailouts (Global)

- TARP (USA): The Troubled Asset Relief Program provided around $700 billion to rescue major banks, mortgage lenders, and financial institutions.

- UK Bank Bailouts: The British government spent about £137 billion to rescue Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), Lloyds, and HBOS.

- Irish Bank Guarantee: Ireland guaranteed €440 billion in liabilities of its six main banks, eventually leading to a taxpayer bailout.

2. Northern Rock (UK, 2007)

- The British government nationalised Northern Rock and provided billions to keep it afloat following the subprime mortgage crisis, preventing a total collapse and protecting shareholders.

3. COVID-19 Corporate Bailouts (2020-2021)

- Many governments worldwide provided direct support to large corporations, airlines, and hospitality giants to prevent mass layoffs, including billions to airlines like Lufthansa, British Airways, and Air France.

4. Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) Restructuring (UK, 2009-2015)

- After initially bailing out RBS in 2008, the UK government continued to support its restructuring, holding shares for years before starting to sell them at a loss.

5. Chrysler and General Motors (USA, 2008-2009)

- The US government stepped in with $80 billion to rescue Chrysler and General Motors, with restructuring deals that allowed management and investors to avoid complete losses.

6. Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) Bailout (USA, 1998)

- The US Federal Reserve coordinated a private bailout worth around $3.6 billion to save this hedge fund, fearing global economic disruption from its collapse.

7. Bear Stearns (USA, 2008)

- The US government brokered a deal for JPMorgan Chase to buy Bear Stearns at a fraction of its market price, backed by a $30 billion loan guarantee to cover potential losses.

8. Credit Lyonnais (France, 1990s)

- The French government rescued Credit Lyonnais with about €20 billion in aid, covering significant investment losses and fraud issues within the state-owned bank.

9. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (USA, 2008)

- The US government took over these mortgage giants with $200 billion in backing to stabilise the housing market, allowing investors to hold onto assets.

10. Savings and Loan Crisis (USA, 1980s-90s)

- The US government spent approximately $125 billion to resolve the crisis in the Savings and Loan industry, allowing wealthy investors to avoid total losses.

11. AIG Bailout (USA, 2008)

- The Federal Reserve loaned $85 billion to AIG to keep it solvent after its credit default swap bets failed, protecting banks with significant AIG exposure.

12. Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena (Italy, 2016)

- Italy’s government provided billions to save the world’s oldest bank and prevent broader financial contagion in Europe.

13. Banco Espírito Santo (Portugal, 2014)

- Portugal bailed out this major bank by injecting around €4.4 billion into a “good bank,” Novo Banco, to keep the financial system stable.

14. South Korea’s Chaebol Bailouts (1997-1998)

- During the Asian Financial Crisis, the South Korean government and IMF provided extensive support to major chaebols (conglomerates) like Samsung and Hyundai.

15. Royal Bank of Canada (Canada, 2008)

- Although Canada’s banks did not collapse, the government provided $114 billion in financial support to maintain liquidity during the 2008 crisis.

16. Swissair (Switzerland, 2001)

- The Swiss government contributed to a rescue package to save the national airline after a liquidity crisis, protecting Swissair’s wealthy investors.

17. Continental Illinois (USA, 1984)

- The US government guaranteed all depositors and large creditors of Continental Illinois, then the seventh-largest bank in the country, after its collapse, introducing the concept of “too big to fail.”

18. Spain’s Bankia Bailout (Spain, 2012)

- Spain nationalised Bankia and injected over €19 billion to prevent a banking crisis, protecting high-profile investors and large depositors.

19. Rolls-Royce (UK, 1971)

- Facing collapse, Rolls-Royce was nationalised by the British government, protecting jobs and investments of wealthy stakeholders and preserving national pride.

20. Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank (USA, 2023)

- The Federal Reserve and FDIC acted to protect depositors and stabilise financial markets after these banks’ unexpected failures, effectively guaranteeing uninsured deposits and reducing losses for high-net-worth clients.

These bailouts often spark public debate, as governments argue that they are necessary to prevent broader economic fallout, while critics claim they socialise losses while privatising gains for the wealthy.

Here are 20 notable instances where the UK government bailed out or provided significant financial assistance to wealthy individuals, large corporations, or the financial sector:

1. Northern Rock (2007)

- The UK’s first major bank run in 150 years led to the government nationalising Northern Rock, injecting billions to stabilise it and prevent wider financial instability.

2. Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) Bailout (2008)

- During the financial crisis, the government provided a £45.5 billion bailout for RBS, effectively nationalising it and holding onto these shares for years.

3. Lloyds TSB and HBOS Merger (2008)

- The government brokered the merger of Lloyds and struggling HBOS, providing around £20 billion in bailout funds and guarantees to prevent wider banking collapse.

4. COVID-19 Corporate Bailouts (2020)

- During the pandemic, large UK firms received billions in state aid, including British Airways, Rolls-Royce, and McLaren, through loan schemes like the Covid Corporate Financing Facility (CCFF).

5. British Steel Bailouts (1970s, 2019)

- British Steel was nationalised in the 1970s and received billions in subsidies over the years. In 2019, the government provided emergency funding to keep the company running temporarily.

6. Carillion (2018)

Carillion was one of the UK’s largest construction and facilities management companies, handling contracts for critical public infrastructure like schools, hospitals, prisons, and transport. In early 2018, Carillion went into liquidation with debts of nearly £1.5 billion after years of financial mismanagement, excessive borrowing, and aggressive accounting practices.

7. Bradford & Bingley Nationalisation (2008)

- After the bank suffered huge losses, the government nationalised Bradford & Bingley, covering £50 billion in liabilities and protecting wealthy investors.

8. Equitable Life Bailout (2000)

- Following a pensions crisis, the government provided a compensation scheme of around £1.5 billion to protect policyholders, many of whom were wealthy investors.

9. British Leyland (1975)

- This major UK car manufacturer was nationalised after a bailout package worth nearly £1 billion in today’s terms. The government eventually injected over £11 billion to keep it afloat.

10. Thomas Cook (2019)

- Although Thomas Cook eventually collapsed, the government provided emergency loans and funding to repatriate British tourists, indirectly protecting its wealthy creditors.

11. London & Continental Railways (LCR) Bailout (1998)

- LCR received substantial financial backing from the government when private funding dried up for the Channel Tunnel Rail Link, securing wealthy investors’ interests.

12. UK Coal Bailout (2015)

- The government provided financial assistance to UK Coal to wind down its deep coal mining operations, covering pension funds for shareholders and executives.

13. Co-operative Bank Recapitalisation (2013)

- Although not directly bailed out, the Co-op Bank received regulatory support and a capital injection, safeguarding wealthy investors’ and institutions’ deposits.

14. Network Rail Debt Write-Off (2020)

- The government took on Network Rail’s £10 billion debt to stabilise its finances, supporting high-net-worth investors in bonds and other stakeholders.

15. HS2 Project Overruns (Ongoing)

- With ballooning costs for the HS2 project, government funds continued to cover costs, indirectly protecting wealthy contractors, landowners, and investors in the infrastructure industry.

16. Rail Franchising Subsidies (1990s-Present)

- The privatised rail industry has received billions in annual subsidies, with companies like Virgin and Stagecoach benefiting from taxpayer-funded bailouts to cover losses.

17. British Energy Bailout (2002)

- The UK’s main nuclear power producer received a £650 million rescue package and further financial support, protecting investors from a potentially catastrophic failure.

18. London Capital & Finance (LCF) Compensation Scheme (2019)

- After LCF’s collapse, the government provided a £120 million compensation scheme for investors, many of whom were wealthy bondholders.

19. Greensill Capital (2021)

- While not a direct bailout, Greensill Capital was indirectly supported by government-endorsed lending schemes, safeguarding wealthy investors until its collapse.

20. Silicon Valley Bank UK Rescue by HSBC (2023)

- The UK government and Bank of England orchestrated a last-minute sale of SVB UK to HSBC for £1 to protect British tech start-ups and wealthy depositors from losses.

These examples reflect how the UK government has historically stepped in to prevent the collapse of key industries, financial institutions, or companies to safeguard the economy, jobs, and often wealthy investors’ interests. One of the key reasons we cannot trust private entities is their quickness to raid the bank of the general public.

Here are 20 instances in the UK where government policies, regulations, or initiatives significantly benefited the wealthy, often exacerbating economic inequality:

1. Privatisation of Public Utilities (1980s)

- The Conservative government privatised industries like British Gas, British Telecom, and water companies, offering shares at discounted rates. Wealthy investors who purchased shares profited immensely as these industries became lucrative.

2. Deregulation of the Financial Sector (1986 – “Big Bang”)

- Deregulation under Margaret Thatcher’s government allowed the financial sector to expand rapidly, leading to enormous growth in wealth for bankers, traders, and financial professionals in London’s financial hub.

3. Council House Right to Buy Scheme (1980s)

- While intended to help council tenants own homes, this scheme saw wealthier individuals and property developers buy discounted housing stock from councils, profiting from rising property values.

4. Reduction of the Top Income Tax Rate (1988)

- The Thatcher government reduced the top tax rate from 60% to 40%, significantly benefiting high earners and contributing to greater wealth accumulation among the rich.

5. Capital Gains Tax Reduction (2008)

- The Labour government cut capital gains tax from 40% to 18%, favouring wealthy investors and asset holders, allowing them to retain more profits from investments.

6. Inheritance Tax Threshold Increase (2010s)

- Successive Conservative governments raised the inheritance tax threshold, enabling wealthy families to pass on more wealth without taxation, preserving family wealth across generations.

7. Help to Buy Scheme (2013)

- Originally intended to help first-time home buyers, this scheme drove up house prices and benefited wealthier homeowners, landlords, and developers more than lower-income buyers.

8. Quantitative Easing (2009-Present)

- The Bank of England’s massive quantitative easing (QE) programme, which began after the financial crisis, inflated asset prices, particularly stocks and property, benefiting the wealthy who hold the most assets.

9. Non-Dom Tax Status (Ongoing)

- The UK’s “non-domiciled” tax status allows wealthy individuals who claim their permanent home is abroad to pay little or no tax on foreign income, attracting billionaires and wealthy elites to London.

10. Reduced Corporate Tax Rates (2010s)

- The Conservative government cut the corporate tax rate from 28% to 19%, benefiting large corporations and their wealthy shareholders by increasing post-tax profits.

11. Bankers’ Bonuses Exemption (2009)

- The UK opted not to implement strict caps on bankers’ bonuses following the 2008 crisis, allowing large payouts to persist within the banking sector and benefiting high-paid bankers.

12. Enterprise Investment Scheme (1994-Present)

- This scheme provides tax breaks to wealthy investors backing small companies. While it supports business growth, it also primarily benefits high-net-worth individuals looking for tax-efficient investment opportunities.

13. Financial Support for Private Schools (Ongoing)

- Private schools in the UK benefit from charitable status, allowing them to pay reduced taxes. This indirectly benefits wealthy families who can afford private education, reducing their costs.

14. Stamp Duty Relief for First-Time Buyers (2017)

- While aimed at helping first-time buyers, this relief drove up demand and house prices, ‘inadvertently’ benefitting wealthy property owners and landlords.

15. The “Patent Box” Tax Break (2013)

- The UK introduced a lower tax rate on profits from patented products, primarily benefiting large pharmaceutical and tech companies, increasing returns for wealthy investors and executives.

16. Pension Tax Reliefs

- High-income earners receive substantial tax relief on pension contributions, a policy that allows the wealthy to accumulate more retirement savings tax-free compared to lower-income earners.

17. Financial Support for the Housing Market (Since 2020)

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, the government implemented measures to support the housing market, including a stamp duty holiday, driving up prices and benefiting existing property owners and landlords.

18. Offshore Trusts Loophole (Ongoing)

- The UK allows certain types of offshore trusts, which enables wealthy individuals to protect wealth from tax liabilities, enabling them to accumulate assets with minimal tax.

19. Low Taxes on Dividends vs. Income

- The UK has long taxed dividend income (from investments) at lower rates than regular income, benefiting wealthy shareholders who derive significant income from investments rather than salaries.

20. Planning Laws Benefiting Developers (Ongoing)

- Loosening of planning restrictions, especially under recent governments, has allowed wealthy property developers to make substantial profits, often at the expense of affordable housing availability.

These policies, often aimed at promoting investment or economic growth, have disproportionately favoured wealthier individuals and widened the gap between the rich and the rest of the population. The concentration of wealth among the UK’s highest earners has led to increasing criticism of policies that appear to socialise risks and costs while privatising profits. The UK, alone, has over a two trillion pound personal debt and yet it has to keep bailing out those who are creating it.

All of the above enable us to conclude that like most governments, not only in the UK, the major political parties are not focused on the best interests of the mass population but the most wealthy. Whereas, people like Jeremy Corbyn were prepared to challenge it; Keir Starmer and his crew merely joined the gang and offer us no progressive alternative.