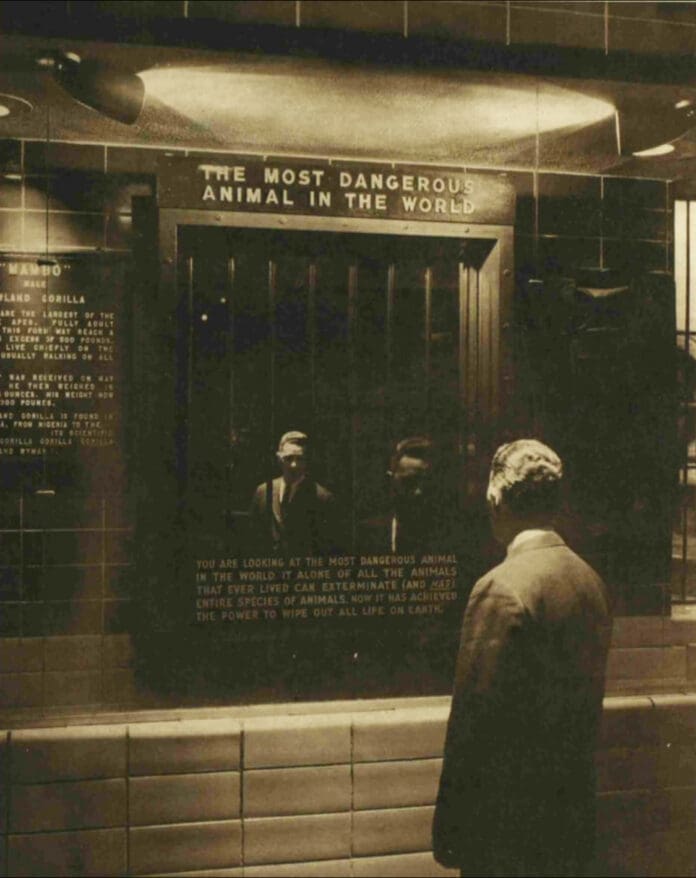

In 1963, the Bronx Zoo unveiled an exhibit that stunned the public—not because of what was inside the cage, but because of what wasn’t.

A large sign hung above a barred enclosure, boldly declaring:

“The Most Dangerous Animal in the World.”

Expecting some terrifying predator, visitors stepped forward and peered inside. But instead of a lion, crocodile, or any other apex predator, there was only a mirror. Beneath it, a simple placard drove the message home:

“You are looking at the most dangerous animal in the world. It alone of all the animals that ever lived can exterminate (and has) entire species of animals. Now it has the power to wipe out all life on Earth.”

The exhibit was radical, stark, and hauntingly accurate. It forced people to reckon not with the natural world’s terrors, but with their own reflection. It was a bold philosophical and environmental statement during a time of Cold War anxiety, nuclear proliferation, and growing ecological awareness.

But the real power of this exhibit lay in its timelessness. More than six decades later, the message rings louder than ever.

Humanity: Apex Predator, Reluctant Steward

Humans have long viewed themselves as separate from—or superior to—nature. We marvel at our ingenuity, our capacity for art, our ability to reason. But we often overlook the darker side of our dominance: our unique capacity for destruction, both deliberate and careless.

Where other predators kill to eat, humans kill for ideology, greed, entertainment, and convenience. We reshape landscapes, divert rivers, burn forests, and mine the Earth’s core. No other species exerts such global influence, nor leaves such devastation in its wake.

To contextualise this stark reality, consider the following table:

Table: Some of Humanity’s Most Catastrophic Acts

| Event / Phenomenon | Date / Period | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| The Holocaust | 1941–1945 | Systematic murder of ~6 million Jews, plus millions of others. |

| Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima & Nagasaki | August 1945 | Over 200,000 deaths, ushering in the nuclear age. |

| Transatlantic Slave Trade | 16th–19th centuries | Over 12 million Africans enslaved; cultural, human, and generational trauma. |

| Colonial Exploitation | 15th–20th centuries | Cultural erasure, resource extraction, genocide (e.g., in the Congo, Americas). |

| Industrial Revolution Pollution | 18th–19th centuries | Initiated large-scale environmental degradation and fossil fuel dependency. |

| Deforestation of the Amazon | 20th century–present | Loss of biodiversity, global CO₂ increase, irreversible climate effects. |

| Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster | 1986 | Long-term radiation effects, ecological damage, displacement of thousands. |

| Climate Change (Anthropogenic) | 20th century–present | Rising global temperatures, sea levels, weather extremes, mass extinctions. |

| Plastic Pollution Crisis | 1950s–present | ~12 million tonnes enter oceans yearly; irreversible impact on marine life. |

| Species Extinction (Sixth Mass Extinction) | Ongoing | Estimated 1 million species threatened by human activity. |

| Overfishing & Ocean Acidification | Ongoing | Collapse of marine ecosystems; disruption of global food chains. |

The Power of the Mirror

The Bronx Zoo exhibit didn’t just accuse—it challenged. By showing people their own reflection, it asked a series of uncomfortable questions:

What role do you play in the harm done to the planet? Can you change your habits? Can we, as a species, turn the tide?

The mirror, in this context, became more than glass—it became a moral confrontation. It invited awareness, even guilt, but also the possibility of accountability.

Are We Still the Most Dangerous?

As technology advances, so too does our power to destroy—or to protect. From AI and biotech to green energy and space exploration, humanity is reaching new heights. But these tools are double-edged. Nuclear energy can power cities—or annihilate them. AI can assist in conservation—or spread misinformation and automate warfare.

We are still writing the story of what kind of animal we truly are.

Hope in the Reflection

Despite our grim record, there is hope. Global movements for sustainability, wildlife protection, indigenous rights, and social justice are gaining ground. Conservation efforts have saved species like the bald eagle and the giant panda. Nations are waking up—albeit slowly—to the urgency of the climate crisis.

The same mind that split the atom can also heal the planet. The same hands that destroy can also rebuild.

But to do so, we must first look in the mirror—not just once in a zoo, but constantly—and recognise what we are, what we’ve done, and what we can become.

Final Thought:

When the Bronx Zoo unveiled that mirror in 1963, it wasn’t a spectacle. It was a warning. Today, as the planet faces intersecting crises, that warning remains a call to action.

The most dangerous animal in the world is still staring back at us. The question is: what will we do with that knowledge?