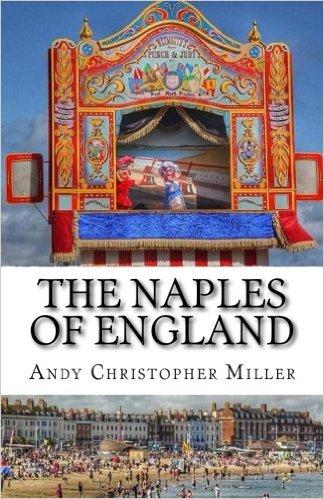

Starting today in Dorset Eye we are privileged to present the whole serialisation of Andy Miller’s book ‘The Naples of England’. Over the coming weeks each chapter will be accessible to all readers.

Enjoy!

Published by Amcott Press

68 The Dale

Wirksworth

Derbyshire

DE4 4EJ

The names of people and locations used in this book are pseudonyms

Andy Christopher Miller 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission of the publisher

www.andycmiller.co.uk

THE NAPLES OF ENGLAND

1946 – 1965

-

Safe as Houses 9 When the Music Stops 13 Message in a Bottle 17 Common Knowledge 23 Every Sparrow Fallen 29 One for a Jack 35 In Scarlet Town 41 Pecking Order 45 The Naples of England 51 Like Survivors 59 Only a Book 67 Mentors for the Atomic Age 73 Racing Right Away 83 Fifty Miles is a Long Way 89 Telling You How to Live 97 Gainful Employment 103 Above and Beyond 113 Concrete Proposal 121

1983 – 1987

-

As Long As Everyone’s Alright 131 Neither Shape Nor Shadow 141 Acknowledgements 150

Chapter 1:

Safe as Houses

‘It was them ruddy Japs,’ my mother said.

Johnny Forrest’s dad was slap bang in the middle of the road right outside our house.

‘They were cruel devils, they tortured their prisoners,’ she added.

He was ‘a nice fella’, Johnny Forrest’s dad, my Mum said. But now he was red-faced and raging at the top of his voice. Normally, he was softly spoken and polite. Today it was forbidden swear words and little else.

‘That’s how it left poor devils like him’.

There was nobody there as the obvious recipient of his anger and our neighbours were all indoors avoiding their windows.

‘Come away. Somebody will fetch him’.

Usually, though, a comfortable web of activity surrounded our lives at number 100 Purbeck Road. A green double-decker bus, on route to the King’s Statue down on the seafront, grumbled past our house, shuddering with its gear change just before the entrance to The Rec, on the hour, at twenty past and at twenty to.

The road sweeper made sleepy brush strokes along the gutter outside our hedge on hot summer days. From about the age of four, I would rush for my mother’s broom if I heard his metal barrow clanking along the road. I followed behind him as his apprentice providing the finishing touches and was rewarded with elegant piles of sandy dust, twigs, leaves, lollipop sticks, cigarette packets and matchboxes.

Another regular along Purbeck Road in the years before I went to school, was Mrs Crosby, the afternoon paper lady. Whatever the weather, she wore a headscarf and gabardine coat stained and stiffened by newsprint. Bent in upon herself, with a hooked nose, and hurried, indistinct vocalisations, she wheeled a daily bulk of South Dorset Gazettes in a baby’s pram. I used to frequently ask my mother if I could help Mrs Crosby and was told that I must not make a nuisance of myself. Like a tiresome dog that brings back a stick too quickly, I would be at her side asking for another paper to deliver, making more work than I spared her.

The baker made a perfunctory bread delivery at mid-morning every day and the Co-op grocery boxes arrived each Tuesday. My mother seemed a little ill at ease with the eager banter from the bespectacled, lanky man who brought these provisions, who actually stepped inside the back door to place the heavy cardboard boxes directly onto the top of our kitchen cupboard.

For me, the most exciting of the street-based merchants who trekked across the Shorehaven estate was the fishmonger. His heavy wooden barrow, with swinging pails of fish and sculpted weighing scales with iron weights, creaked along our road in the early morning. His cry, intriguing but also, like Mrs Crosby’s diction, menacing in its indecipherability, would sometimes wake me on summer days. Fresh West Bay mackerel, caught during the night, were announced in a voice growing louder as it approached.

‘Wheeeeeeeey…..Krull!’

The surprise breakfasts that followed, the meaty aroma imperious about the kitchen, the salty sea filtered through the fibrous flesh. Like childhood itself, never as immediate again, never so exquisitely recaptured.

There were the less-told tales though, the ones reserved for my times alone with my mother. Her voice would drop to a heavy whisper with breathy emphasis. Her shoulders became hunched as if she had to shake the most distressing words from her lips by means of a rapid, sideways shaking of her head.

‘Those camps, when we saw them on the newsreels at the pictures after the war, I just couldn’t believe it. Belsen. Those wretches, they weren’t human. All skin and bone. Couldn’t walk some of them, had to be carried. Like skeletons. I couldn’t bear to look, couldn’t get it out of my head. I kept seeing them for ages.’

Vivid, all around her for my mother. It was the lived present. The panorama and the spectacle of war, the defiant rhetoric of Winston Churchill. The huge, shared purpose. The horrors, the moments when the restraint slipped. The persistent and recurring memories.

All in the past for me. Before my birth, before my life. It was history, as were cavemen and Romans. I was born at the beginning of a New Age. 1946. The world had been scoured, scorched and cleansed at a terrible cost. Chance had chosen me and my generation to be its most fortunate beneficiaries.

Chapter 2: When The Music Stops

‘Hold his feet. Somebody get his feet’.

‘Ooof!’

Clanking machinery somewhere out of sight jolting my padded chair another notch upwards, the Big Wheel’s juddering progress towards the sky. My arms held down by my side, then my legs, the rubber mask pressing ever more firmly into my face. A last intake of breath, clawing at the oxygen. Its effects easily spent, the steady hiss from the machine overpowering my rhythms. A final wrench of one shoulder, twisting at the waist, firmly pushed back and pinned down. My hold on the present weakening further and then extinguishing. Echoing voices, metal implements, searchlights brought down closer, thick fingers on my face then in my mouth, the sensations becoming vaguer as I float upwards in the huge chair. Heavy, scraping levers, rusty cog wheels misaligned and almost failing to connect. The huge arc swept out by my oppressors, their cold technology and me slumped in my chair, moving together slowly through one whole revolution. The friction from a brake as if burning against iron, the circular momentum restrained, the click and clang as we become stationary and level with the room again, the bolts locking us securely back on firm ground. Blood in my mouth.

‘That’s it, good boy. All done. Have a rinse and a spit in here if you want to’.

There was a choice at the dentists, gas or cocaine. Both had their detractors, each their horrible mythologies. For me, being smothered into sleep seemed preferable to the needle in the jaw. Victor Critchley had shown me with his hands the length of the needle that had punctured his brother’s mouth. It must have been driven, eight inches or more, through the thin strip of gum, through upper tooth and bone, on into the soft cerebral tissues and finally out through his eggshell scalp and tangled hair into the daylight. The dentist was inescapable with surprise school inspections sprung upon us at various ages. The agents of the State, we knew, maintained scrupulous records in which any absentees were noted, to be followed up by personalised appointments delivered in official brown envelopes to our very homes by their tireless ally, the postman.

Our docility and captivity within school were exploited again and again. Cycling proficiency tests were inescapable for all bicycle owners. White-coated doctors, the most feared of all, descended and appropriated corridors and offices seemingly without challenge. Whatever they required was provided and we stood anxiously in line for them, bragging, tearful or fighting back the terror.

‘When you’re in the fourth year they come and you have to cough or something and then they touch you on your balls,’ or so the rumour went.

Greater than these terrors though was the communal care provided us. The children’s section of Weymouth public library, although hushed and proper in tone, let us loose amongst its vast bounty. Huge school dinners – carrots, peas, gravy, suet and pastry, pies, puddings and custard. Women who lived on the Shorehaven estate, our near neighbours, reappeared at lunchtimes in the school hall dressed in overalls, cheerfully plying us with food, judging the most deserving for the ‘seconds’ queue, on rare occasions even signalling with wide eyes the opportunities for third helpings. Then afterwards we were led into the school hall and seated cross-legged on the polished, springy floor to listen to radio programmes created especially for us. Mounted up towards the ceiling, large varnished speakers with circular golden grills beamed down reassuring voices into the hall.

‘Hello children. Do you remember the song we have been learning about a sixpence? When the music stops Uncle Brian will be here to teach you the next verse’.

Each note from the piano reverberated around the room, haunting harmonics high in the hall. Occasionally children slumped to the floor to be scooped into a more comfortable position by patrolling teachers, even covered with small blankets in winter, while the rest of us were entranced further by the respectable, measured diction coming from the speakers. Our teachers and these kindly broadcasters in an easy partnership, furthering our nurture.

We would not go hungry. We would be comforted.

We were to be protected from preventable disease.

We were to aspire. We were to have knowledge and then to know even more, right out to the very boundaries if we wished.

Next week Chapter 3 Message in a Bottle and Chapter 4 Common Knowledge.

If you would like to buy the book click here.