BY ANDREW CHRISTOPHER MILLER

Chapter 12

Mentors for the Atomic Age

My earliest years at school and the final one or two stood out as exciting excursions through a stunning landscape of human accomplishment and knowledge. The intervening decade or more, by contrast, seemed like an unending trudge through featureless marsh and scrub.

The greatest treat in my infant school years, for instance, took place at the end of the final year when I was seven. Our teacher, Miss Cartwright, took our whole class to Rossi’s ice cream parlour all the way up on the seafront. Its dark, fan-cooled interior had always seemed the territory of the visiting holidaymaker. On that day though, an area at the back was cordoned off and reserved just for us. We still rushed between the other tables though to claim our seats as if they were rationed, the winner takes it all. Local children, we asserted our right to partake too of the banana split and the knickerbocker glory. The slower, the weaker and the more polite were pushed to the back or pulled from their seats. Miss Cartwright attempted to rein back the boisterous excesses with kind words and smiles, the wounded and the dispossessed congregating around her skirts, vying limply for a place at her table. I assumed Miss Cartwright’s wealth to be substantial, she was paying for everybody and many attempted to seize huge chunks of her generosity for themselves.

‘Can I have an American ice cream soda?’ Karl Jospin yelled, trampling us with his worldliness.

And Miss Cartwright laid out other gifts before us through the year.

‘What happens when you’ve done all the red books?’ I once enquired.

‘There are the brown ones’.

‘And what’s after that?’

‘Then there are purple ones’.

‘And what’s after that?’

‘Then you can choose from the library corner, anything you want. And in the summer, there will be a trip to the public library down by the harbour. You can become a member’.

‘What’s after subtraction?

‘Then it’s subtraction of hundreds, tens and units’.

‘And what’s after hundreds, is it called thousands?’

‘After that we go on to something completely new’.

‘What’s that called?’

‘It’s called multiplication but you probably won’t get there until next year’.

A waitress in a uniform brought a tray of fizzing drinks, orange and raspberry, some in bottles with straws, two straws to each bottle, and others in moulded glass tumblers. Cakes on a large plate were brought, one for each of us from a selection. Elizabeth White on my table grabbed for one of the two cream buns, ‘I’m having that,’ and then three of us lunged for the other. Karl Jospin won, stamping the back of my outstretched hand with his fist and pulling at the cardigan sleeve of my distant cousin, Janet.

‘Look, I’m drunk,’ shouted Elizabeth, her mouth full of cake and the bottle in her hand spilling, as she feigned an escalating wooziness.

‘No, look, I’m drunk,’ countered Karl and as he opened his mouth for a roar or an intoxicated dirge, a huge belch emerged instead. After the briefest flicker of panic, his bullfrog laugh became the loudest of all. And then he vomited. A forceful orange fountain splattered across the table and then, as he turned in disarray, a second less intense expulsion lodged itself in the coarse green weave of Elaine’s cardigan sleeve, a chorus of disgust rising from our table, chairs kicked back in escape, an acrid odour, a sticky anxiety, the pollution of our feast.

Not all my teachers elicited the affection that Miss Cartwright so easily evoked although most provided a serviceable focus for my wandering imagination. My parents had no fond memories of their own schooling, my mother never mentioning any individuals by name as if for her they had all coalesced into one solid mass of authority to be resented and avoided. ‘I had no concentration that was my problem. If somebody said I had to do something, then I didn’t want to. Defiance it was, I suppose’. My father, on the hand, had their names – Bug Welford, old Freddie Babb – contempt or fear, I was never sure which, fuelling the listing of their nicknames. He had a line of whitened skin across the base of his right hand little finger, I used to see it and feel its ridge when my brother and I lay in bed with him some Sunday mornings when we were young, each of us working a hand and wrist as if a puppet, him doing the voices while my mother made cups of tea downstairs.

The scar was the result of a lifelong wound, well almost lifelong, inflicted by a teacher’s cane when he was seven years old. On his first day at junior school, the deputy head had entered my father’s classroom and fired arithmetical questions around the class. My father had mumbled a reply when his turn came, correctly but inaudibly, and was summoned to the front and instructed to extend his left hand.

The closest I came to such depravities, punishments that my father always seemed to judge as well deserved, was in my final year in the junior school. I had somehow been selected for Mr Stoddard’s class, the eleven plus crammer. We’d been creamed off we were told, thirty nine of us, and we were to be pushed. Every day, whether sodden from a downpour on the walk to school on a gloomy, winter morning or enlivened by the spirit of a new spring filled with sunshine, we performed our lightning speed observances. Mental arithmetic, tables and addition and subtraction. The missing figure, the next in the sequence, the odd one out. And spellings, more and more spellings. Old Stoddard, lean, elderly and mean spirited, patrolled our cowering rows, beating out the pace, demanding participation. My back straightened, my arm jabbed upwards, my body was alert and twitching as if sensing a kill. All day it seemed we were drilled in these routines, all day except for the regular blocks of time when the others were in the playground and I was indoors under his peripheral view writing out lines, ‘I must learn to behave myself in class,’ ‘I must concentrate and avoid silliness’. However many of these lines I accrued, all logged meticulously in Stoddard’s punishment book in red ink, still more were showered upon me.

‘It says ‘Crude Oil Production’ on this poster. Look, it says ‘crude’. That’s rude’.

‘Miller! One hundred lines, I must learn to control myself in class. By Friday!’

Sometimes my backlog seemed to tower above me at an unstable height, my left-handed scrawl slowing to a crawl, completion and my eventual freedom seeming impossible. Once, seeing a new depth to my despair, my mother offered to produce some of the pages herself.

‘Now, how do you want me to do these? she asked. ‘I used to be in trouble at school, my Mum got proper cross with me if I took home a bad report. Don’t tell your Dad I’ve helped you’.

Her rounded, flowery letters bore no resemblance to mine, the forgery would be apparent to all. It was an ill-crafted attempt and bound to fail.

‘That’s not right. It’s too curvy. He’ll see it straight away and know it’s not me!’

I passed for the grammar school nevertheless and my world cleaved. New people, new buildings in a new area of the town, important-sounding subjects, room changes, and a heady swirl of laboratories and foreign languages. And for a while school felt more settled. I became purposeful, engaged and more anonymous. But within a couple of years, bottom of the top form in all my end of term exams, I was back to being academically ill-at-ease and regularly serving after school detentions on Thursday nights.

All my reports spoke of unfulfilled potential and a persisting immaturity. One evening in particular our whole class was kept in after school for some collective misdemeanour by a lanky and much ridiculed religious studies teacher. At twenty past four, most of the girls were allowed to leave while the rest of us continued to copy set passages from the Bible. Others who had settled to their task without wise-cracking were allowed to exit in dribs and drabs as the clock hands dragged silently through first five, then six and eventually seven o’clock. By that time only two of us were left bent over our pages and then Mr Chivers let the other boy leave. Suddenly feeling dry-mouthed and vulnerable, I suffered in an appalling silence sensing that some act of unspeakable indecency was about to befall me.

Mr Chivers walked down the aisle to my desk and then hoisted himself in his heavy jacket and trousers up onto the wonky individual desk in front of mine. He perched there precariously, the informality he seemed to be seeking so obviously eluding him, and then I sensed him bending down even closer to my bowed head.

‘Miller …’ he began, with what seemed to me to be a ring of feigned affection. ‘Miller, is there anything wrong at home?’

*

My father’s belief in rationality and scientific advance was a matter of faith. ‘You can’t argue with progress, Andrew,’ he often told me. And it was true that I did feel myself privileged to be living in modern times, standing with everybody else at the perimeter of the Atomic Age. Indeed, a little later, as sixth formers, my physics class was taken on a special visit to the nearby Winfrith nuclear power plant where we climbed the short iron ladder and stood in our school uniforms on top of the reactor. I bent to touch its roughened surface, the few feet of warm and vibrating concrete beneath our feet that separated us from a caged, minor sun struggling to burst out into the universe.

The bright beacons of education would lead us all out from the evils borne of ignorance. It would have spared my parents and the whole adult world the Dark Age they had had to live through. And yet the agents of this enlightenment – old Stoddard, Mr Chivers and all the rest of them – seemed to me remarkably ill cast for the heroic duties that history was forcing onto them.

Miss Cartwright had shown us affection but we had been very young then. The first teacher who seemed to me to be in step with the urgency of the times was Irene Fletcher, the biology teacher at my grammar school whom I first met when I was thirteen through membership of the Field Club. This club focused ostensibly on the natural world and landscape and met after school in the biology lab as well as for weekend walks in the surrounding countryside. Most members were a few years older than my friend, Paul, and I but we were tolerated as we joined them at benches on high stools, surrounded by glass fronted cupboards containing rows of old stained jars inside of which organic entities pickled away. The discussions sported a high degree of play acting and histrionics as we considered matters as diverse as art, aesthetics, theology and literature, the energetically-suppressed courtship of some of the older ones being an embarrassment we feigned not to notice as the price of our inclusion.

Irene was treasured by the older pupils as a confidante, an advisor, and a safe refuge from the prim anonymity of their early 1960s home lives. On first name terms outside of school, she dressed on walks in a white fisherman’s jumper and blue denim jeans, clashing with all my previous experience of teachers. Some of the older pupils had been known to walk from Weymouth the whole five miles out along the beach road to her cottage on Portland, to share with her their struggles for identity, to seek counsel over parents, or to share with her their latest creation – a sketch, painting or poem.

After a year or so of membership, there was the sensational announcement of a Field Club party to be held at Irene’s cottage on a Saturday evening. At fourteen, the last party I had attended would have been my own birthday six or seven years earlier when Brian Roberts had ripped his best grey flannel jacket on barbed wire on the way. My mother, equally or more distressed, spent much of the event attempting to effect an invisible mend in the heavy material. Clearing the debris afterwards, we both knew, and with some relief, that this would be the last one. Enough of the sweat and bruises, the acid regurgitation and the wild urination.

But a party at a teacher’s house! My parents fussed over the clothes I should wear, were insistent on my showing respect, remembering my manners and being polite. ‘It’s not that sort of a party,’ I snapped but I was really as anxious as they were, none of us having any template for the life lived beyond this social threshold.

‘Just remember to do what you’re told, if anybody asks you’.

‘Dad! ‘

‘Well, nobody ever got anywhere, you know, by proving the boss wrong’.

Irene’s cottage was a battered, pink-washed, double fronted building. I was welcomed into her softly-lit living room where a type of music I had never heard before, a lazy saxophone wandering around a brushed snare drum, was playing. Her chairs were much smaller than ours and made of unvarnished wood, there was no linoleum on the floor just mats on top of bare stone. There were paintings on the walls, real ones, nudes even and melancholy figures, some of them vaguely familiar. The older pupils stood in the centre of the room talking loudly and sipping drinks. A few of the boys were wearing cravats beneath open-necked shirts and some of the girls, in what seemed an absurd attempt to mimic grown women, were wearing nylons and smeared make-up. Irene offered me a glass of brown ale, only my second ever alcoholic drink. I struggled to understand the conversation of the older pupils and certainly could offer no contribution.

Feeling tense and alert, swimming in the malty tang of my drink, the rows of books provided a secure fix for my attention. In our living room at home, we had a bible, an old encyclopedia, a digested compendium of Dickens, and I curated my own slim collection of Enid Blyton, Just William and Biggles books. On Irene’s shelves, however, were rows and rows of books with green or orange spines, paperbacks, their titles provocative and sophisticated. I scanned them with my head tilted to one side as the effects of the brown ale pulled me further over and down towards the floor – ‘The L-Shaped Room,’ ‘Vile Bodies,’ ‘The Heart Is A Lonely…’

‘Everybody, everybody. Here’s a challenge, a competition. You have to find the roundest pebble on the beach you can. The winner is the most aesthetically pleasing curvature, the smoothest pebble. Don’t get lost!’

Outside in the blind night, zig-zagging winds buffeted the worn edges of the last line of buildings before the shingle bank. Here was a challenge I could meet. I pulled at rocks embedded in the ground, tears of excitement blurring my vision as I palmed their chilled surfaces.

My life of running, the hiding and the seeking, now entering a world of new and expanding possibilities. Indefinite tracks leading off into the future, journeys hinted at with only the briefest of directions, journeys that I could not and would not refuse to undertake.

The heart indeed a lonely hunter.

Chapter 13

Racing Right Away

In 1963, I obtained a summer job in one of the arcades on the seafront collecting money on the bingo stall owned and operated by Jack and Mary West. I stood with Mary inside, collecting the sixpenny stakes from the double rows of plastic seats that surrounded us on three sides. Jack sat on a swivel chair on a raised platform, hunched behind his machine bubbling with coloured and numbered ping pong balls, microphone in one hand, cigarette in the other, weariness sagging through his frame.

‘Come on in, we’re racing right away. Come on in’.

Circumspect, regular with my weekly wages, these two had somehow ended up in the artificial light of an amusement arcade on a Dorset seafront. But, Mary told me, in their younger days they had travelled the world in a South African circus, turning their hands to whatever was required with Jack even facing the lions in their cage. ’Show him what they did,’ she one day said to Jack and, after further cajoling from her, he reluctantly raised the back of his shirt – great angry swipes across the whole of his back, permanent registrations carried across continents.

‘Eyes down, looking in’.

The outside world pulsed through the gossip of the regular players. The majority of the clientele were predictably regular, a tightly defined and almost entirely female demographic. Buzzing between them collecting their dues, I could pick up the latest snippets and titbits from the Profumo affair. I had carefully torn black and white photos of Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies from my father’s Daily Express at home and stashed them away. It was unbelievable to me that women so shamefully desirable, grown women not girls, actually existed somewhere. My mother must have found and disposed of them because they always disappeared.

But the whispers on the bingo stall were as much, or more, concerned with the trial of the osteopath, Stephen Ward. I looked up the word ‘osteopath’ in a dictionary but the prosaic, paramedical definition gave no clue to the real substance behind the frisson that this seemed to generate both in newspaper accounts and among the clucking rows of bingo players. And then one day, raised excitement rippled around the two rows, shocked gasps, greedy whispering, back and forth – Stephen Ward had committed suicide! First, John F Kennedy and now this.

Christine Keeler, Mandy Rice-Davies and the McGregor sisters, Carol and Mary, who lived two streets away from me on Bodmin Road. A rumour went around the kids up at the Rec one night when I was about fifteen

‘Mary McGregor was down the Sports Field without her clothes on last night. Anyone could have a feel. They say she’s going down again tonight’.

I could barely raise my voice loud enough to ask Alan Avery whether this was really true.

‘Straight up,’ he said. ‘Our Jimmy was there, said you could see everything’.

Even more weakly now, ashamed of my need for the information, I asked him if he knew at what time.

Mr McGregor was in prison according to my father but he would not say what for. I was, however, able to obtain from him enough by way of reassurance that it was for not for murder or violent, armed robbery. Intrigued as well as unsettled to be living so close to a professional class criminal, I was warned away by my father.

‘A nasty piece of work and no mistake. Prison’s the best place for him’.

As a child I believed that my parents could name every person resident in Weymouth, that they could tease out the links between an entire population, knit together every loose scrap of knowledge, each acquaintance and relation. And it had become clear that in this web were shared understandings, somehow operating at a level inaccessible to me, of crimes pushed deeply beneath the daily discourse of the town. Hidden and unspoken too were the true activities of osteopaths.

Karl Jospin and Carol McGregor stood near the entrance to the Field that night and watched me closely while I avoided their eyes. I had barely seen either of them in seven or eight years, our destinies after infant school having been determined first by junior school catchment areas that carved up our estate and then by the ‘eleven plus’ which sealed their lifelong separation.

There was a busy mass of bending figures discernible in the half light up by the further goal posts as I passed Karl and Carol with my head bent towards the ground. They looked at me in silence, neither smirking nor calling out. Feeling wretched and exposed, I tried and failed to concoct at least for myself the deception of some other purpose or destination.

At the scrum, I recognised some of the fat-thighed boys who were pushing and snorting as coming from our estate. But there were also strangers who must have travelled from other parts of the town. My heartbeat and shivering limbs settled a little when I realised that there was nobody else from the grammar school. With individuals curiously anonymous and unspeaking, I grappled to extend a hand between the bodies and into the centre of the circle, to reach and touch flesh and resolve the mystery, to subdue the insistent pull into shame and misery. Dropping to my knees, I could see between their legs a figure on the ground, presumably Mary McGregor, and extend my hand to touch something human, maybe her arm or perhaps her thigh. It was not her breast, I was fairly sure, but the indiscriminate jostling threatened too many blows and bruises if I persisted in my grim desire. Somebody said that Karl Jospin had Durex and I felt even more sickened.

Down at the entrance to the Field, Karl and Carol were standing side by side in the twilight facing two older youths whom I did not recognise. There was something passed between them, the sense of a negotiation, a compromise or a surrender.

I next saw Carol McGregor about a year later up on the promenade in the furnace heat and bustle of a midsummer’s day. Arm and arm with a lad a little older than me, not somebody I had ever noticed before, they strode together like a couple on a poster advertising escape and fulfilment in their little seaside resort. Wholesome in her billowing dress, full-hearted roses on cream, held in at the waist by a large white belt, her happiness was impossible to hide. Although she had been one of the less pretty of my infant school companions, her smile that afternoon, more than her permed brown hair and the make-up, propelled her into the sunlight, a world away from the degradation that had dried up my mouth that evening down at the Field.

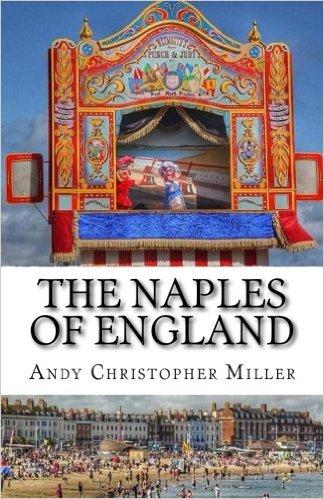

I watched them walk all the way to the Jubilee Clock, feeling lighter myself, as they reached around each other’s waists, then resumed their linking of arms, before crossing the road and disappearing towards the side streets down by the station. The sauntering crowds swallowed up their absence and the afternoon heat built further, the wind off the sea carrying children’s cries of laughter and protest, fragments of Mr Punch’s menacing whine, the intermittent clack of deckchairs on their stack and the toffee-like aroma of donkey droppings.

And then that same afternoon, only an hour or so later and before the teatime thinning of the crowds, I saw her again. Among the promenading couples and families, the small children scraping metal spades along the esplanade and the teenagers sitting in a row along the railings, Carol was walking again in an excited embrace but this time with a sailor in full uniform. His bell-bottomed trousers were flapping as they crossed the road, leaving the open air, holiday bustle and disappearing down those very same side streets.

Come on in, we’re racing right away.

Next week Chapter 14 Fifty Miles is a Long Way and Chapter 15 Telling You How To Live

If you would like to buy the book click here.