BY ANDREW CHRISTOPHER MILLER

Chapter 18

Concrete Proposal

‘Creativity in Concrete’

That’s what it said across the top. And then below, the soaring line of a bridge. Sculptured and white, stretching as far as a rainbow’s end across a sky of brilliantly saturated blue. Nothing else, just this clean, perfect geometry.

At the bottom, the words ‘Careers in Civil Engineering’.

We were in the sixth form hut. Mr Michaelson was distributing the green UCCA forms and the mood was subdued. Something serious was about to happen, something that was possibly irrevocable. And I had left it too late to find out what and to undertake preparatory action.

Although my friends and other kids in the sixth form talked about applying for university, my thoughts always wandered somewhere else at those times. In fact, my thoughts were not thoughts at all but a diffuse and comforting muzziness into which the sights and sounds of the outside world melted and became muted.

Friends said things like ‘Sussex is supposed to be good for history’ and it puzzled me. I knew roughly where Sussex was but not the nature of this purported link. Why not say, for example, with equal conviction that Dorset was good for history? For my parents and myself, grammar schools had been some way beyond our understanding, institutions that engendered our respect and also a little fear. Sixth forms were definitely foreign territory and anything further brought no image to mind.

My father tried to keep abreast of these matters and passed on what he had discovered to me.

‘They do these three year sandwich courses where you do the theory at the university and have the middle one out in industry where you put it into practice’.

Industry! The word itself filled me with dread never mind having to turn up each morning at a factory. Chimneys belching out smoke, a decaying urban sprawl all around, clocking on, artificial light, the rumble of heavy machinery. I could happily sing along to ‘Dirty Old Town’ and feel the frisson of meeting my love by the gas works wall. I could even see that train set the night on fire. But actually believe that in less than a year I would be smelling the spring on the sulphur air? It was impossible.

Mr Michaelson was reminding us to read the instructions at the top of the green form carefully because it would not be possible to correct any errors later. There were boxes where we were required to enter the degree topic or topics of our choosing.

‘What are you putting?’ I asked Tony Bridges next to me. He had shown no hesitation when faced with the empty boxes.

‘Civil engineering’ he said in a worldly way.

‘What’s that?’ I asked.

Without looking up from his paper, he reached into the breast pocket of his blazer and produced a folded leaflet, the one with the beautiful arc of a newly constructed suspension bridge spanning a pristine sky.

Creativity in concrete. It had a ring to it and my only other plans lacked any specificity. I had diffuse but intensely felt desires to spend my life among intellectuals, writers and artists. But, despite experiencing occasional shivers of excitement at one or two of Keats’ metaphors or feeling terrified out on the marshes with Pip, I had failed miserably in my English Literature ‘O’ level. I also longed to possess an overview of the huge historical forces that had shaped my world but had trouble distinguishing a Tudor from a Stuart, a Whig from a Tory. I was easily fired by political rhetoric and the plight of the underdog but had no appetite for local party meetings or parochial policy discussions. Again, I could imagine myself immersed for life in musical composition and performance but was unable to rub two notes together in tune.

Science subjects, physics and maths, were the only areas in which I could achieve some examination success. Or, to put it more honestly, these were the only fields in which I did not fail to reach a pass mark. Early in my sixth form career I had experienced the thrill of realising that universal laws were just that. They were universal. They could describe both the motion of the planets and the bucket of water that I swung around my head on the beach as a child. The invisible clockwork governing the universe. A moon could smash into its neighbouring planet in the same way that the water could fall from the pail onto my head. And – and this was the wonder of it – with some arithmetical calculations on a piece of paper we could calculate the tipping points for both. Even I could do that! I could defy the water and determine the course of the stars.

Creativity in concrete. The end of my search. The fusion I had been seeking suddenly, and in the nick of time, revealed.

Into the empty box on the sheet in front of me I inserted, in the specified black ink, the letters that I believed might seal my destiny:

C-I-V-I-L-E-N-G-I-N-E-E-R-I-N-G

*

With these forms completed and out of my hands, I felt freed from further nagging questions about my future. I had been required to nominate six establishments and had hedged my bets by choosing three of what I understood to be old and established universities and three of the newly-created colleges of advanced technology. Now I could leave this paperwork to complete its journey through a network of in-trays and filing cabinets in alien towns and cities across the country. Through the winter my commitment to my studies at school increased and I managed to find more focus, a concentration disrupted regularly though by music and thoughts of girls. But the numbing denial of what I was to do after leaving school could not last and early in the new year, I began to receive rejection letters from the higher education establishments that I had selected.

I might still believe that Gopher was mistaken when he had expressed doubts about my suitability for his sixth form. But these official letters dropping one by one on to our doormat certainly confirmed my fear that I was now attempting to reach beyond my abilities, beyond the modest ambitions of my family and beyond the painstakingly-mapped and familiar terrain of the Shorehaven Estate and our seaside paradise.

And then an acceptance. In the sixth buff envelope, an offer of a place, contingent only on the most basic of A-level passes. I had been accepted to study civil engineering at Salford College of Advanced Technology. I could retreat from unsteadying thoughts of the future back to the security of the present.

Apart from my climbing trip to Snowdonia a year or so earlier, the furthest north I had ever travelled was to Bristol once and London a couple of times. A quick check in an atlas revealed the complicated and extended hitch hiking route that would be needed to make a return visit home from Salford, a journey that might well not be possible in one day. So, I engaged myself even more fully with my A levels to the exclusion of these wider matters. But the deadline for my decision moved towards me under its own volition until I could avoid it no longer. I waited until the last possible day then, ignoring my father’s warnings about birds in hands and bushes, I declined the place.

For the rest of the school year, while my friends made plans, I focused on a succession of more immediate landmarks – a dance on Friday, Easter holidays, asking a girl in the year below me to the pictures, my first A level exam and then each subsequent one. Acquiring a summer job, meeting my weekly deckchair sales. In this way, I managed to concern myself with the moment and nothing much more right through until the pinnacle of the town’s tourism activity – August Bank Holiday Monday.

Records broken, temperatures soaring, the beach and promenade a dense swarm of bodies like a scuffed anthill or a disturbed colony of wasps. With every deckchair stack sold out, our thousands upon thousands of visitors spread themselves beneath the sun in a torpor or made their way between stalls and shops with slowed down movements, spreading sand across roads and pavements. Scurrying, quick and nimble, around and in among these huge crowds, local people attempted to cater for their every gaudy appetite and within those few peak weeks harvest an income that could be eked out across the remainder of the year.

But then, the lay-offs, those who had drifted into the town at the beginning of the summer floating away again into the margins of big cities elsewhere, friends packing cases and booking journeys, the rounds of good-byes and the ruddy enthusiasm for reunions. By the second week in September, I was one of the few employees remaining and attempting to sell a few nine-penny deckchair tickets. On a particularly wet Sunday, my father came along the promenade with a copy of the Sunday Times under his raincoat.

‘There’s a list here of all the courses that still have vacancies for this year,’ he said, awakening in me a queasy feeling that the bustle of the summer had managed to suppress.

‘Don’t go turning your nose up at it,’ he added. ‘You say you want to go to London, well there’s places in London on this list.’

The deserted beach had been freshly raked and aerated by a council vehicle that morning and the light rain that was now falling dimpled the surface with soggy pin pricks. I was aware of the concern behind my father’s actions but was too absorbed in my own confusion and apprehension to appreciate or even acknowledge his efforts. I took the paper and stored it in our works cloakroom before returning to my stretch of promenade chairs. The weather had driven away my only customers, a small group of elderly ladies on a day trip from Crewkerne, so I passed the time until my lunch break throwing a stick that a sodden black Labrador had brought up from the beach and dropped at my feet. The dog raced with enthusiasm and without tiring up and down the ramp onto the beach, impervious to the deadening mood created by the wet mist blowing in across the bay. I needed to make a decision and take some action. To commit to the next step.

The next day, aware that my final pay packet was only a week away, I gathered together a shilling’s worth of pennies and walked round to the telephone box outside the shop on Mendip Street. After rehearsing my opening question until I felt confident, I made the long distance call to London.

The conversation was brief and successful. I would be in London within the week, sleeping at night on a settee in the library of Bob’s boys club in Bermondsey and walking the streets of south east London by day looking in newsagents’ windows for lodgings in a more convenient location.

I would live far beyond the unchanging skyline of hills that held in my home town. I would leave behind the seas that massaged our shores daily with every tide. I was impatient with the familiar, hemmed in by security. I would come alive in the anonymity of the city, alert to its dangers and unpredictability.

I dared to hope that my place to study civil engineering at Woolwich Polytechnic would at last provide my entrée into the world of poets and philosophers.

1983-87

Chapter 19

As Long As Everyone’s Alright

‘Dad says I shouldn’t have told you. I mustn’t say anything else’.

It was December 27th, 1983. My mother and I were back in the kitchen again doing the dishes after tea while the others settled in the living room to the television or the new toys. The computer, the Sinclair Spectrum, was dormant now, disconnected and inert on the kitchen table. I had been wondering all day when I might get the next opportunity to speak with my mother. Down in Buxton’s Pavilion Gardens, my two older sons had raced around the ornamental landscape, disappointed that there had been no snow over Christmas but shouting to their grandparents to watch them swing on trees, career down a slippery bank, test out their footing on the rocks across the culvert. I had held my youngest son’s hand whilst my parents admired and shouted. ‘Watch out!’

‘Oh, my godfathers, he’ll be in there, I can’t bear to look’. ‘That’s him to a tee, always a little monkey’.

We might have very little time. The pull of the computer had been intense, there had been hardly a moment when the rubber keys were not being stabbed or when the slow connection to the cassette player was not flickering away, downloading.

‘Dad says it was wrong to tell you. You mustn’t say anything to your brother’.

It had been the same the evening before, an explosive flash flood with events and memories careering past as my mother and I stood in the kitchen washing up after Boxing Day tea. It was only supposed to have been a casual enquiry in an attempt to tidy a few footnotes in my curiosity before the real work, if there were subsequently to be any, could begin. There had been two recent television series about tracing family trees and both took a diligent and reverential approach. Like Songs of Praise, wholesome and reassuring. It was said to provide a fascinating insight into the unwritten history of ordinary life down the ages. For those with the will and aptitude, here was an invitation to the famous, huge archives in London. Or, age-weathered parish records could be accessed in out of the way village churches, with a system of charges constructed around half crowns and guineas, and turn-around times for correspondence stretching into many months.

Not for me really. I could see the appeal of securing my family and myself within the branches and twigs of the centuries, but this was a world of cardigans, old books and a slowed-down appreciation of the delicately savoured fact. I had a full-time job as an educational psychologist, a young family, a rock climbing hobby and friends, all deserving more of my attention already.

Not yet, except for the one injunction:

‘If you are thinking of doing this, talk to your oldest surviving relative today. Don’t wait until tomorrow, do it today!’

So I told my mother that I was thinking of tracing our ancestors. She often talked of her earlier life, creating vivid pictures of herself as, for instance, a giggling schoolgirl crammed with others into bathing machines on Weymouth beach, struggling out from school uniforms and into one piece swimming costumes, to balance and tiptoe, suppressing squeals, out along the slippery struts shelving into the sea. Or, the night in the war when the land mine exploded on the beach, the sky shaking with orange fire, a thunderous crater on the sands right in front of the gracious, Georgian facade of our seafront hotels. ‘They were after the dockyards, see, and Portland Harbour’. As a child this history had pulled itself about in my contemplation – bathing machines from the very earliest black and white photographs in history books or from the novels of Thomas Hardy, somehow jostling with the murderously modern and metallic.

Then there were the people, her relatives. Old Salisbury Granny, my mother’s granny. She was totally blind and had a terrible time with Grandad, her husband, I was often told. He led her a right dance at times apparently but he couldn’t help it. ‘Poor old Salisbury Granny’. She was lovely, my mother said, so calm and patient. Poor as church mice. My mother as a young girl had to place money carefully in her hand – ‘Fetch me my purse, Dot, I want to see what I’ve got’ – so that she could palm the coins.

Mum’s granddad had been in the Boer War. ‘That was the cause of it all’ my mother said. ‘He was a proper old soldier’. I heard many times of the day he told her Granny he was going out for cigarettes, only to board the bus for Weymouth, all of forty miles away, to end up on the Esplanade marching back and forth all on his own in front of the military band performing for the holiday makers. ‘He led poor Granny a dance’. The bus route to Weymouth wandered over dusty whaleback ridges and through empty Dorset farm country. Hours and hours he was gone. It was an unimaginable distance to me at the time, him so far from Granny’s orderly surrounds, so helplessly available for the crowds’ amusement. ‘As soon as he heard a band, he was up there, swinging his arms’. My mother would swing hers too, even march about before me sometimes, as she recreated him. ‘I’m just going out for some cigarettes, Queenie – that’s what he called her, Queenie – I won’t be long’.

I imagined Mum’s grandad nimble and alive within the music, in scarlet with gold buttons like a Chelsea Pensioner, defiantly on parade up before the Jubilee

Clock. This tower with its four clock faces, a blue and red column with ornate gold brocade, could be seen from the entrance to the railway station. It heralded the approach to the grand and trivial escapes offered by the sand and sea. The pompous thump of the brass band, the children’s release on the crowded beach, gulls and the breezy crests on tiny waves in the shallows, all bolstering the frothy business of being alive. Word somehow reached my mother’s family that he was there, all the way from Salisbury, up on the Prom. Somebody had seen him marching back and forth in front of the Jubilee Clock, with everybody laughing, and him oblivious. ‘And poor old Granny worried sick about where he was’.

I knew these stories well, these people. I imagined their faces in my childhood in a later century. I walked through the same landscapes. But these two, my Mum’s grandparents, belonged to an era as distant as the historical wars of the Crimea and Transvaal. The television programmes had helped me realise that there were others closer in time to me, others I should have known far better who were missing and unmentioned.

‘I never knew Dad’s mum, did I? I’ve always assumed she died before I was born?’

‘Dad’s mother died a long, long time before you were born’.

‘I knew Granny Miller wasn’t Dad’s mother, but I don’t seem to know anything about his real Mum. When did she die?’

My mother held up the dinner plate she was drying and stared hard into its empty face.

‘Oh it was years ago, our Dad was only a little boy. He never talks about it’.

‘Gosh, I hadn’t ever realised, in all these years’.

‘Well you wouldn’t. He never talks about it, your Dad’.

‘So, what did she die of?’ I asked and she stopped her slow circular drying.

She stiffened and stared down more intently. ‘She done herself in. In the sea. Off the Nothe, I think’.

The Nothe! Where I had scrabbled as a child along the thin sunless strip of rock exposed at low tide, lifting dense, vile weeds in search of a mouthful of winkles to take home to boil for tea. The Nothe fort, a little beyond the tourist magnets of the beach and town, with ramparts and a sea wall, tunnels and heavy gates, there as a lumpen defence, we were instructed, against sea-borne invaders across the centuries.

My mother turned away from me towards the table, still holding the plate. Granny Miller had to somehow become a less established figure, as I tried to fit another woman, faceless and nondescript, into parts of her dominion. Somebody in a cart-wheeling trajectory against the sky, propelled from the top of the fortification onto the rocks.

‘He’s got a good brain on him, your Dad. He passed for the grammar when most of them, their parents had to pay. But then he had to leave after – when his mother – he had to go out to work to bring in some money’.

So much of it couldn’t be right. I could not be learning about such happenings for the very first time at thirty six years of age. This violent, dramatic death was out of kilter with my whole sense of the past, with the pattern of people in a landscape, the threads and connections of family circumstance.

But there was no time for any further questions. My sons bundled into the room, still full of restless enthusiasm. ‘Is it still switched on? Come on Grandma, we’re all going to play’.

‘Our Dad says I shouldn’t have told you. I mustn’t say anything else’.

She came straight out with it the following evening as soon as I dared raise the matter again. All day, at mealtimes, in the park, around the house as life adapted to the presence of new toys and their demands – furniture and schedules changed to accommodate the Spectrum – I had been struggling to hold the questions in, not to risk intense and furtive enquiries a few paces back behind the rest of the family.

‘Dad says it was wrong to tell you. He won’t talk about it’.

It didn’t occur to me to wonder when this conversation between my parents had taken place. We had all been together in our holiday bustle almost all the time, with Dad and me sitting up late the previous evening drinking home-brewed beer, and Mum surely asleep by the time he and I made our whispering way upstairs. My mother and I could be interrupted again at any moment and a queasy awareness was growing that moments when family details could be exchanged had, in my life, been isolated between periods of silence somehow rigidly enforced over months and even years.

When the opportunity did arise to talk again, on that second evening clearing up after tea, I could think of no obvious or immediate questions. There was so much to re-configure, points of detail seemed potentially distracting and unhelpful. Instead I would have wished for the broad sweep of an account – pictures, words and colour – and, particularly, some explanation as to how I had never heard one hint or slip of the tongue, had never carried through my childhood even the faintest suspicion that, when the adults closed the doors, they communed together out of our earshot with secrets of such disruptive magnitude.

‘Why did she do it? When was this, how old was Dad?’

‘I don’t know. All those children, I suppose. Four children and Grandad away at sea for most of the time. Dad was only a little nipper. He won’t ever say anything about it’.

Four children and the back parlour, the room with the varnished panels, the stairs up into deep interiors that I had never seen and could not imagine, the outside toilet, the squashed-in back yard and the small strip of earth supporting Grandad’s rows of vegetables. Granny Miller fitted there in Newbiggin Road with Grandad in a way that some new, indefinite presence would not. The lens could not focus and no defining outline would emerge from any amount of further facts and figures.

‘What about your mother, then? I never knew her either, did I, but I do remember your Dad, Grandad Shergold?’

‘Can you remember my father?’

Of course I remember him, I used to have my tea with him. But what about your mother? When did she die?’

‘When you were little’.

‘What of?’

The past I had never questioned or investigated, even in my fancies, was unrolling a sensational carpet right in front of me.

‘She did it as well, didn’t she? She did herself in!’

‘She what? She did herself –‘

‘She did herself in. In the house where we lived, Purbeck Road. When you were a little nipper. They lived with us’.

‘But how did she –‘

‘In the gas oven. Stuck her head in one morning. Before everyone was up. It was awful. I scrubbed and scrubbed but I could smell it for ages afterwards. It was in the walls. It was terrible, it made me feel sick. I don’t like to think about it. Even now it makes me go all funny’.

How could any of this be true – one grandmother in the sea, another on the floor in the kitchen? All my mother’s stories, all the family characters in a loosely-formed tableau, all my persistent questions as a child piecing together the links. We had been revisiting them for thirty-five years. How had we managed to weave around these two women, to sidestep them as we galloped or dawdled along? My mother would often lose herself in the stories, becoming gruesomely vivid and engrossing to me as a child. She re-lived the parts, sometimes became one character after the other, the events tumbling out beyond her control. Lost in another time and body, she would be pulled back into the present by my father. ‘Steady on now, mother, come on’.

It seemed like a kindly, family joke. Well, almost. ‘You were getting a bit carried away with yourself there’. My mother’s animated account would die away and she would ease back into the room, returning to us far more subdued, offering perhaps a parting comment to her companions – ‘a proper matelot he was’ or ‘poor old Granny’.

And then my sons came in one by one, drawn back to the Spectrum.

‘Grandad says he wants a rest from Scrabble. ’

‘Are you ready for a go on the computer yet, Grandma? Grandad’s going to read the paper for a while’

‘Oh I don’t think I can do that, my dears, I can’t seem to get the hang of it’ Why had it never occurred to me to wonder or to ask? If there were stepmothers, then there must have been mothers. It was obvious, but it was also an inaccessible thought. If this was true, then my father had lost his mother as a little boy, possibly with his own father on the other side of the world, far away at sea. There had never been one reference through all the years, no name, no slip of the tongue – no photograph. The things children shouldn’t hear, I never heard. My curiosity had always pursued every corridor and room it encountered, there could be no locked door let alone a secret wing left unnoticed and unexplored.

Life could not possibly have been so ordinary. My parents could not have been the safe, predictable people they so clearly were, if any of this were true. I had been insulated from these deaths so completely by a protection almost chilling in its effectiveness. My mother offered nothing more, these huge family dramas from either side of the Second World War fading back into wherever it was that they were so securely accommodated. And yet that War itself had not been put to rest, it had been a daily talking point all through my growing up. I could feel no connection with the bereaved little boy in the panelled back room or the young woman in the tiny kitchen reeling from the sulphurous stench. This could not possibly be true. I could not have been so fundamentally wrong. I would have known. I would have had some inkling.

But there was no more time to question my mother, even if I could have found any focus and remained out of earshot of my sons. My father then walked into the kitchen carrying a small pile of empty plates that we had missed.

‘This is what I like to see, people working. Don’t stop on my account,’ he said. ‘Everybody alright out here then?’

‘Oh yes, we’re alright’ my mother replied. ‘We’re just chatting’.

‘Just putting the world to rights’ I added, the words coming automatically.

‘As long as everybody’s alright, that’s the main thing’ he said, carefully inspecting the brown quart bottles with thickened glass necks and tightly secured stoppers that held in the final fermentation of my home brewed beer.

‘I suppose it’s a little too early for you, isn’t it Andrew? What about you, Mam, not too early for you, is it?’

Chapter 20

Neither Shape Nor Shadow

After my mother’s revelations, my whole understanding of the rooms of our house in Weymouth had to stretch to accommodate another person, not some visitor at our door but an extra unsettled presence, my Mum’s mother, already intimately within.

Neither shape nor shadow had remained. I had not retained the faintest remnant of a whisper, a cry or a sharp command. In our compact house, among the right angles, there were no corners or hideaways, no incubation spaces for disease, misery or secrets.

Somehow, if my mother’s revelation was correct, a slumped human body had sprawled across our kitchen floor, an awful anonymity all around her despairing death, and then she was gone. No memory of brushing together in tight places, no waiting for an extra adult to take her turn, no prior claim on Grandad’s attention and no disturbing of the peace. Somehow, the stories, the characters, the turnings of the year fitted perfectly together. There were no missing connections and no persisting hint of sulphur in my nostrils.

In 1987, after a professional conference in Bournemouth, I made a return visit to the Shorehaven estate. I parked in Cheviot Road around the corner from Purbeck Road and walked back and forth through the streets and lanes, weaving loops and patterns as I covered every familiar step, going nowhere in particular until I stood on the opposite side of the road looking at our old house. The privet hedge was gone, the garden paved over and open to the road to allow car parking.

All that work, our boundary with the outside world. Every leaf in the hedge had been kept in check, groomed as carefully as any stabled horse. The vegetables that fed us, the chrysanthemum petals in their thousands that my Dad seemed to inspect individually for signs of pests. Obliterated.

I wanted to march up and knock on the back door, to be shown around, to have my story acknowledged and to hear the history of the last twenty years. Instead I set off around the block, cutting in through The Rec, the huge municipal beasts having been replaced with smaller slides and swings, underlain with spongy safety materials. Around the block, down Pennine Road where I had walked to and from junior school twice a day, little seemed to have changed. Some gardens were scruffier. Nobody would have tolerated a waterlogged newspaper strewn across their front garden in my childhood years. But some also asserted self-improvement with small front porches and nameplates. The substance, however, was unchanged, the warm red bricks flaking only a little more, the tarmac road perhaps a little more substantial and less patched, the quiet pace of neighbourhood undisturbed.

I stood again opposite number 100, willing myself to knock the door. This was not a place I felt I could tarry. Strangers were still noticed. Everybody I had seen during my walking had been unfamiliar to me. I would feel foolish undertaking another lap. And then I was somehow knocking on the back door. How many times had I knocked on doors around here and then run away as a child? Please let there be nobody in. What was I doing? What would I say if somebody answered? I could still run away. And then I knocked again. No, no, no. Please let there be nobody at home.

I looked down at the backdoor step and the configurations flashed into place. The concrete oblong, the chipped corner, the slight scoop about the size of a penny, and another a bit smaller, the sheen of an embedded pebble and two other smaller ones beside it. Not a memory, not some impression distantly familiar. More a template, vital and right at the forefront of my mind but never fired or triggered through all the intervening years. The exact pattern – instantaneous recognition and delight rushing up through my body with an intensity that all the walking and other nostalgic musings of the day had come nowhere near to matching.

I had come right down to eye level with my soldiers on this step as a child. The saucer of milk had been placed at one end to tempt Timmy, the ginger tomcat from across the road. Prince, the mongrel from Mendip Road, had arrived here every morning one summer holiday, pawing the door to be let in before I was even out of bed. Arriving home from junior school in the winter, to tomato soup or occasionally a boiled egg from our neighbour’s hens. Sitting out here in summer before Sunday lunch, the radio coming through the open kitchen door. Jean Metcalf in London and Bill Crozier in Cologne. ‘From all of us over here to all of you over there’. BFBO. Brough and Archie Andrews. The Billy Cotton Band Show. My Dad, ready to carve the meat, appearing at the door to sharpen the knife. ‘Come on now, let the dog see the rabbit’ – my cue to move so that he could swish and scrape the blade back and forth, faster almost than the eye could see, scissoring the step.

‘And if you can’t find a partner, use a wooden chair, but let’s Rock!’

I couldn’t run and the door was opening. A man with a large belly, his vest swelling over the top of his partly unbuttoned trousers stood rubbing his eyes and trying to recognise me.

‘I’m sorry. I was just passing and – um. I used to live here’

‘Used to live here? Come in. I’m sorry’ he said scratching his dishevelled hair. ‘I work Saturday mornings, I’m a plumber, and I have a drink lunchtimes. Come in. I was just sleeping. You must be – What’s your name?’

I told him.

‘That’s right. There was that suicide. Your mother wasn’t it?’

‘My grandmother!’ I forced out in alarm.

He knew. I was hardly back in the kitchen after twenty years and he had come straight out with it. I hadn’t considered this aspect, somehow supposing that, when my mother had told me at Christmas a few years earlier, the catastrophe had been tidied away from everybody’s memory in a day or two, that nobody else had paid it much attention if they had even noticed at all. But he’d blurted it out within seconds, whereas they had held it within themselves each and every day of the nineteen fifties and the nineteen sixties. Or, at least, in my presence they had.

Round the corner in Pennine Road, Aunt Hilda had known but I had never heard her speak. Across from her, Mrs Symons held sway, a woman not to get on the wrong side of, my father said. She sold toffee apples from her kitchen door around bonfire night, her Alsatian dog eyeing each of us customers as if making a mental record, and we knew not to complain that the sticks splintered in our mouths, or to try to see past her in case there were any bigger ones on the tray inside her kitchen. She had known. She had sons older than me, one of them, Shorty, not having been right in the head, my mother said, since he fell out of a tree collecting conkers on Southwell Avenue. He wouldn’t have known, or at least he wouldn’t have remembered after his accident, but his older brother might have. I admired Alan Symons, he was tall and confident and I used to watch him chasing girls with stinging nettles up at The Rec, threatening to brush their bare legs. He might just have been old enough to know.

Across the road from us, Mrs Devaney would have known. When I was in the sixth form I heard her expressing exaggerated surprise to my mother that I would be staying on at school for yet another year, her Robert being the same age and already half way through his apprenticeship. Next door to them, Mr and Mrs Shilitoe, marooned with their daughter Alice who had Down’s Syndrome, kept their quiet counsel. And they had known. Boys sometimes congregated at their front gate and as Alice sat moon-faced at the window they shouted ‘Monkey!’ and put their hands to the sides of their temples, wriggling their fingers and making sounds of disgust. ‘Poor Mrs Shilitoe, with that Alice. It’s a shame,’ my mother said, the source of the pity a daily presence.

Next door again, an old man we called Fogey Dyke, grumpy and red faced. One summer evening in my early teens, I led my brother across the road to his yellowing laurel hedge, armed with unwanted, over-ripe tomatoes. Once the first one had been thrown at his front door, we disgorged the rest with fire in our limbs, vulnerable now with our cache still in our hands, the soft thuds still falling, trails of juice and seeds sluicing down his door and walls. The neighbour who had observed us running back home and informed our father and old Fogey Dyke himself – they may both have known, they may have made allowances or taken quiet note of early slips into deviance.

Clive Varney’s Dad, cycling past the house and whistling on his way to work, steering his bike with one hand. His loss, his other arm blown off in the War, was there for us all to see. Away from his cheerful progression along our road, in a garden shed or beside an allotment bonfire perhaps, he may have occasionally weighed his severed bone and flesh against a terrified exit from life by means of a gas oven.

Mary Brownlow, two houses down from Mrs Symons, gave me a lift on her Vespa scooter once or twice in my teens when we both worked on the bingo stall in the seafront amusement arcade. Like most of my neighbourhood contemporaries, swiftly through secondary modern school and out into work whilst I still walked to and from the grammar school through our estate in my blazer, cap and tie, her queries seemed to be without envy. ‘Are you still squatting for exams?’ she once yelled over her shoulder as we jumped a ragged gear change and wobbled with screaming revs into the attack on St Martin’s Hill. Mary might not have known but, hemmed in behind a small front garden of wayward couch grass and wild barley – no hedge, just cast concrete posts and broken strands of rusty wire – her reclusive mother would have secreted this knowledge away somewhere in her gloomy living room.

But my brother and I heard no word, never a slip of the tongue nor a mysterious allusion. There was no malicious barb from the kids at The Rec, no overly condescending care or concern from the adults around us.

So, where and how had secrets been archived in these streets and houses? The immediate reference to the suicide showed that the trace was still charged and undimmed. The story was alive, the account still jumped the dislocations between person and time. The impact of the kitchen step, dull and ordinary but able to trigger an unstoppable carnival of colour and sound, screamed an unanswered challenge to the other doors that could be seen from our back step, as close and closed as they always had been.

The plumber opened the kitchen door wider.

‘You’d better come in. I’m sorry, I’m still a bit asleep’

‘No, I’m sorry. I really shouldn’t have disturbed you. I was just walking by, visiting, and I thought – you know’.

‘Do you want a cup of tea? How do you like it? It’s a bit tricky tea isn’t it, sometimes. I’ll put the kettle on’.

There was no under stairs cupboard in the kitchen, no structure at all. Instead an alcove had been constructed and this now housed a small, bronze-topped telephone table and a stool. The walls were sculpted white in textured paint and the kitchen appeared at least twice its former size. I remembered that my mother had sometimes been sickened by the thought that a mouse was living in the boxes of junk at the very back of the cupboard and we had interacted only with items stored near the front.

‘God. That used to be an under stairs cupboard, all that. My Grandad used to keep his…’ and I was unable to speak, taken over by the life we had lived in that room.

‘It’s alright, son’ he said, although he was little older than me. ‘This tea’ll be ready in minute. Got to let it boil though, haven’t you? Do you want a look around?’

‘Sharon!’ he called and a young woman, blonde-haired and wearing jeans and a white T-shirt, appeared from the living room. ‘This chap used to live here before us, before you were born. Show him around will you, while I sort this tea out’.

‘Alright’ she said ‘but you haven’t forgotten that I’m going out though, have you?’

I wanted to apologise again for intruding but I also wanted to be left alone to rummage, not to be escorted in what had been my own home, the place where all my childhood had been spent. Sharon too had lived almost all her life in 100 Purbeck Road shocking me from my assumption that, apart from my brother, I had to be the only person to have come from birth to adult independence here. She was casually territorial, while I stared into the bathroom, the toilet, and her bedroom, deeply severed from what had once been mine.

‘It’s just incredible that somebody else has… I mean, my whole childhood… I can’t really…’ I fumbled.

Sharon herself might well know. If so, had my grandmother’s death become part of some spooky tale she relayed to her friends? Or did it elicit reserve and a quiet privacy?

‘Dad!’ she suddenly shouted, unsettling me as I must have unsettled her, ‘’I’m staying over at Kelly’s tonight. You’ve remembered, right?’ A blue holdall was lying open on her bed, curling tongs and a toilet bag showing through the half-zipped top. In my old bedroom, there was a dressing table and mirror, with lipstick, make-up, necklaces and earrings spilled across its surface.

My teachers! Had they all been aware of our circumstances? And doctors. Did they keep records of such things in their files back then?

‘Tell that chap his tea’s ready,’ the man shouted and I welcomed the chance to join him back downstairs, away from rooms preserved for me in the mustiness of memory, the windows now flung wide and aired by youth and femininity. My brother and parents, my grandparents even more so, were no more than minor echoes in the last floorboard still to creak and in the stale atmospherics of awkward corners up near the ceiling. A new, careless modernity had usurped it all.

‘I used to lie on that landing floor upstairs with our new transistor radio,’ I told him ‘Between the two main bedrooms. Trying to tune into Radio Luxembourg. My Dad said the reception was good because the electricity cables ran down inside those walls. It was the only chance to hear pop music most of the time. ’

‘You couldn’t get the signal,’ he said. ‘Mind you, it’s not much better now sometimes’.

Sometimes. Cliff Richard had sung ‘Living Doll’ and the Beach Boys ‘Barbara Ann’ with warm, rounded depths and razor-edged harmonies. But then the sound would fade becoming blunt and undernourished. Sometimes foreign languages, urgent and gabbling, would surge over the border, cutting across each other, growing louder and unchecked. At other times, I would attempt to tune the dial through an absolute minimum and be met by sounds from between the planets or the bleak anonymity of a Morse code signal, like some last message from a mass of black Atlantic rock, guano-caked and devoid of vegetation.

The tea was milky and very weak with a film on its surface.

‘That alright for you?’ he asked.

‘Yes it’s fine,’ I replied. ‘Thank you’.

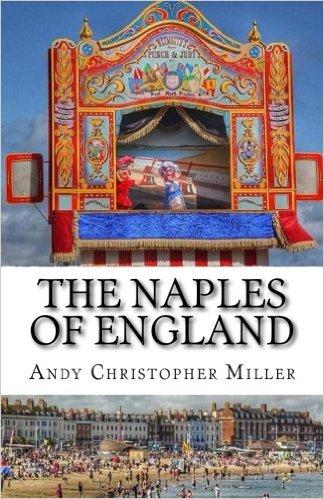

Acknowledgements

The facilities and support provided by Nottingham Writers Studio have made the writing of this book a far more sociable enterprise than it would otherwise have been. In particular, I have enjoyed and benefited greatly from the critical insights of Paul Anderson, Gaynor Backhouse, Angela Barton, Megan Taylor and Frances Thimann. I am also extremely grateful to Alan Appleby, a school friend from sixty years ago (!), for permission to use his photographs for the cover.