BY ANDREW CHRISTOPHER MILLER

Chapter 5

Every Sparrow Fallen

Lizards, snakes, frogs and newts.

We were custodians of the hedgerows, the waterlogged bomb site and the waste ground. Inside the old air raid shelter, erratic movements up the wall. In the dark, among the rubble underfoot, something slithering resentfully away. Turning over large rocks or abandoned sheets of galvanised roofing panel, millipedes, spiders or slow worms writhing and dissipating in all directions into the surrounding grass. If we were really lucky, a lordly grass snake or evil-eyed adder.

For me, an implicit and approximate understanding of the evolutionary ladder was also my yardstick for empathy. Molluscs, insects, things without legs, if they did not cause me fear, elicited contempt. One of my earliest memories was of playing in a friend’s garden and setting out to rid his parents of the pestilence of cabbage white caterpillars. We enlisted the help of other kids in picking them from the stems and undersides of wrinkled brassica leaves while I climbed onto their garden shed, a brick built construction with a rounded metal roof and a chimney. I bent to receive each offering from the others with cupped hands and then, for some reason, dropped them down the chimney. After every half a dozen or so such manoeuvres I also dropped a rock or broken house brick after them with a grandiose sense of adult importance. I found this complicated method of dispatch thrilling, my sense of dispassionate and mechanised efficiency grossly alluring.

Ants, by contrast, were a far more advanced and civilised species than caterpillars, spectacular though the cycle of cocoon, dry chrysalis and eventual, flowering emergence as a butterfly always proved to be. Colonies of ants lived under the path in our back garden and I was intrigued by their intricate collaborations. They dragged objects in convoy and patiently reorganised, without a visible language or method of signalling, to surmount the various obstacles with which I sought to test their invisible ingenuity.

Occasionally though, I showered them with cascades of boiling water. They were a pest and I willed myself insensitive to their imagined screaming and gloated in the adult conversations I had with myself – thinking about it not getting the job done, being cruel to be kind. At one moment entranced with being omnipotent and alive. Later, shamed, disgusted and frightened by the delight and the delusion of necessity with which I had carried out such unpitying destruction.

Set against this though, I was capable of being deeply distressed by the suffering of animals and birds. At nine years old I carried a badly wounded house sparrow in a shoebox on two buses, one to the seafront then another along Dorchester Road, to secure its relief from a vet. I returned empty-handed biting back tears, wondering whether the bird really could be saved by the gentle professionalism of the staff – ‘they always die’ was the view I heard often enough, – but also reliving time and again their warm and reassuring attention towards me.

Separated from adults, we children shared a different sentient world with creatures of the wild. We patrolled the hawthorn, bramble and sedge. Rare sightings were rumoured, the secret locations of nests traded. We depleted the clusters of warmed and speckled eggs responsibly, just one for a collection, secure in Nature’s effortless abundance and its unending replenishment.

But to be included, or at least to wander the estate and fields free from ambush and attack, required the suppression of some sensibilities. The older kids with air rifles could serve as protectors or as patrolling vigilantes. I became craven, wretched in muted collusion, behind Victor Critchley’s hedge one night as his older brother lined up his sights with the ridge along their roof top. Like a pack of hunters finely attuned to each other’s silences, we watched the line of sparrows and starlings squabbling and chattering along the tiles. Pfft! An instant space in the line as the other birds shrieked into the air. Not the zing of spinning tin as at the Fair, rustlers with sly grins in neckerchiefs or Indians with tomahawks. Just a puff of feathered life no more, the slick reloading routine, the muttered acknowledgement of the shot among the older kids.

Greater horrors were related though thankfully never witnessed. The boy, a friendless, spiteful character plucking out the eyes of live baby birds from the nests. Like picking winkles to eat from their shells with a pin but cruel, merciless and cold. After I had been told this, the image would sometimes resurface as I tried to get to sleep at night. I believed that if I never solidified these awful images with my own spoken words then their intrusions would eventually cease. But although unvoiced they still returned and some nights I had to press my own eyeballs in hard with my knuckles to suppress the thoughts and hold myself intact.

When I was nine my Aunt Jocelyn came to stay with us for a few days. On other occasions, Uncle Sid came by himself because they were unable to both leave behind their dog on its own. My aunt’s visits were anticipated by my parents with a dizzyingly high degree of anxiety. My father seemed to increase the amount of overtime he worked when she visited and I was aware of the snatched conversations between my mother and her, worrying away in corners, fast, hushed and watchful, biting back into silence if I approached.

On this occasion, Aunt Jocelyn asked if she could bringthe dog with her. She warned us that it could get ‘over-excited’ but I saw this as no impediment. The vagaries of animal nature were a daily wonder to me and the search for authoritative but reassuring responses one of life’s more welcome challenges. I assured my parents that I would be privileged to take on the major responsibility for the animal’s welfare and amusement if it was allowed to come.

Whether or not this was a deciding factor, I never learned. But the visit took place, aunt and dog together, and on the second night of their stay I was granted a wish greater than I could have hoped for. My aunt and mother had tickets for a show on the pier and had to be out of the house half an hour before my father returned home from work. I assured them that my brother and the dog would be safe in my charge and my mother insisted I locked the door immediately they left and opened it to nobody until my father arrived.

As they stepped out and closed the door behind them, I shivered with pride and a giddy sense of autonomy. But before the door could click closed behind them, before I could shoot the bolts, the dog ran at it and then along the hall to the front without stopping. It hit each door with a full force thud, scrabbled back to its sliding feet, claws flailing against the lino, and wailed dementedly. It barked sharply then careered straight into me, unreachable by command or consolation. As I struggled to my feet to follow, it was upstairs in three bounds, skidding at speed through the landing, bouncing in flight momentarily on my bed like a trampolinist garnering momentum, and then on sailing out through the open window into the warm evening air of Purbeck Road, a howling, convulsing mess of limbs, rigid and broken, down before me on our front lawn.

Chapter 6

One for a Jack

My mother used to say that I wasn’t to go bothering Mrs James, that we had to leave our neighbours in peace sometimes, but every time I knocked on her door it was obvious that she was pleased to see me.

I always asked whether she would like a game of ‘Beat Jack Out of Doors’ and every time she stopped what she was doing and beckoned me into her gloomy back room which was heavy with large and serious furniture. She always brought a plate of luxury biscuits in from the kitchen, macaroons with rice paper or chocolate digestives. She would play her hand carefully and lay down any cards she had to forfeit in an unhurried fashion – one for a Jack of mine, two for a Queen and so on.

‘Come again, Andrew. I’m always pleased to see you, my dear,’ she would say when I left. Or something like that, definitely proving my mother wrong.

I had known Mr James too before he died. I used to watch him over our back garden fence, a respectable and kindly spaceman in his beekeeper’s apparel.

‘Don’t get too close now,’ he once said. ‘They can get upset if there’s any change to their routine’.

And they certainly could. It was actually something as small as a bee sting that ended up killing him one Sunday afternoon when I was ten.

I was playing with some of the other kids up on The Rec. Three of us were lying flat on a swing each and twisting the chains so that we would be swung round and made dizzy when we raised our feet from the ground. Because it was a Sunday I wasn’t allowed out for so long but I had been to church that morning with my mother so there was no Sunday School and I knew I could stay until four o’clock.

That’s why it was a surprise when my Dad appeared at the corner before it was even three.

‘It’s your Dad, Andy,’ Ricky said and I ran to him, curious about his presence. It wasn’t teatime, there were no visits planned and I had fulfilled my religious observances.

‘Come on home,’ he said ‘Right now, I want you at home’.

My father always walked at a furious pace and when I sometimes accompanied him to or from his bus stop on workday lunchtimes, I enjoyed the absurdity of trying to move at such a speed, the sight of his arms and legs in such animation, me having to burst into a run to keep up and maintain our conversation.

But that Sunday afternoon he was so clipped in his speech, with the sense of a coldness only one unnecessary question from me away. I walked as fast as I could behind him, as he powered himself back along the pavement to our house, wondering what misdemeanour of mine had been detected. With an increasing sense of fear, and desperate to confess and relieve the tension, I ran through the various arenas in which I might be at fault – school, the spelling test, my brother, my mum. But I couldn’t think of anything serious enough to warrant this, anything that could have come suddenly to light in the middle of a Sunday afternoon.

Indoors my mother looked at me but said nothing. There was no way I could get her alone to ask her what was happening, to tell her that I had done nothing wrong.

‘Go up to your bedroom,’ my father said and, as he caught me looking towards my mother, trying to demand her intervention, he seemed sharper still.

‘Do what you’re told. Right now!’

From my bedroom, I could hear no sounds within the house. Silence and a sense of absence played about the walls, carpet and linoleum. I had seldom been punished in such a way and was unable to predict the likely duration nor what might happen next.

Then later there were quiet voices in the street, or possibly in our garden. I heard the door of a vehicle being closed, these muffled sounds coming to me through the airbrick high up in my bedroom wall. I opened the door handle through the smallest of fractions, trying to avoid the sprung click of the latch echoing through the hallway like the smack of a stick on a snare drum. Pacing around the creaky floorboards that I knew could be heard from downstairs, I made a careful journey all the way to the window at the end of our L-shaped landing.

There was an ambulance outside next door’s gate, outside Mr and Mrs James’ house, and the discrete conversation and business-like movements of the two uniformed men seemed adult and thrilling. Next door’s back door was ajar. I could hear my parents downstairs. I knew that I should retreat to my bedroom with care but moved with a faster foot, taking more risks. I lay on my bed, drawn deeply into the mystery. The solemnity and the ruptured Sunday afternoon were clearly bound up with the presence of the ambulance. There was an agitation in the air – ambulances glided through our estate only in the most serious of circumstances – but also the beginnings of happiness and relief, a growing expectation that I was not in trouble after all.

When my mother came and told me that I could go back downstairs, she hurried on ahead of me, not available for my questions. In the kitchen the electric oven was heating up. The earthenware mixing bowl was on the side and my father was making a Victoria sponge. He excelled at these, and made great play about the necessity for the oven to be hot enough. My brother had been in his bedroom too and my mother told us both that Mr James had had an accident, that he had been stung by one of his bees.

Stings, cuts, grazes and bruises were the currency of my childhood explorations, a commonplace among the fields and brambles. The oven hummed, its loose handle buzzing as the temperature crept upwards. My father’s jollity and busyness lifted any remaining gloom. The electric light was switched on, obliterating the last trace of dinginess. The oven’s warmth enriched the kitchen and the smell of the rising cake, the sense of a nourishing presence, cheered the whole room, passing on into the passage, the stairway and even the upstairs landing.

A day or two later I was informed that Mr James had died – from a bee sting – or, more precisely, from the heart attack it had triggered. The hives that bordered our back garden were dismantled and removed by men from the council while I was at school a few days later. And, although I dreaded meeting Mrs James across the fence straight afterwards, it felt very important to see again the spot where the colony of bees had lived, to know the exact coordinates of death. Only two rusty wires sagging between cast concrete posts separated this fundamental event from the unstoppable germination and growth within our own garden.

Chapter 7

In Scarlet Town

‘Andrew Miller, go outside! Outside that door! Immediately!’

‘What did you think you were doing?’

(There had been no thought.)

‘Whatever were you trying to do?’

(No intention either. No plan.)

‘Whatever possessed you?

(Nothing had taken hold of me.)

Except, perhaps, the rush of the music and the pounding of the dance. Like a dog biting the wind or barking at the intensity of the moment.

I had been taken up in the immediacy, the impulse, and couldn’t say why I had tripped Julie Dyson. I certainly couldn’t explain it then and I’m not sure I can offer anything more tangible even now.

I do know that I was extremely ill at ease during our singing lessons. It was something about the language, arcane and respectable, and the constant reproaches.

‘Hold your head up when you sing. And stop slouching and mumbling!’

In Scarlet Town where I was born

There was a fair maid dwelling

‘Pull your shoulders back. And smile. For heaven’s sake, smile!’

Made every lad cry ‘Well a-day’

For love of Barbara Allen.

Far, far worse though was the country dancing.

Boys and girls on opposite sides of the hall in equal numbers.

‘Now choose a partner. Quickly, and without any fuss.’

The one or two boys who had a cousin in the class were the most fortunate. They approached quietly and claimed a hand to the relief of both partners. Next the footballers, their easy confidence less prominent indoors but still pronounced enough to lead them towards the prettier of the girls. And last of all, the biggest group in a desperate, uncertain scramble to avoid being left with Dora Bartholomew. Poor Dora, picking her nose, her regulation grey pullover clumsily darned at the elbows and hanging in stringy threads at the cuffs. Her pleated, bottle green skirt stained from a lunchtime spillage. And her smell. Resignation in her big, dull eyes, like an old, sad beast in a pen, selected for slaughter.

Then the positioning, boys with their arms around their partner’s waists.

‘Count the beats and listen to the introduction. Wait for your cue. And … dance!’

Round we clumped, the music maintaining our momentum.

‘Lift your knees up. Skip properly. Look as if you are enjoying yourself!’

Despite my distaste for the whole business, I found myself able to skip in time with the music if I gave it my full concentration. My partner’s waist, however, kept slipping from my sweaty grip and I feared the impropriety of exercising too firm a hold on her. The fixed smile proved to be an additional challenge I was unable to meet.

After a long period of red-faced grimacing and galloping, we boys were asked to sit on the gymnasium benches around the side while the girls practiced their particular segment of a dance. Although I was relieved to be out of the arena, my pulse was still racing. We watched the girls circle the hall. More compliant than us, more genuine enjoyment in their step, more diligent concentration. I stuck out my foot.

Julie Dyson’s sudden impact with my leg and then her two or three step stagger caused me panic. Her knees and hands crashing onto the springy floorboards reverberated through the hall, a terror choking my desperation to confess and be punished. Of all the girls, I had felled beautiful, straight-backed Julie Dyson. Julie who spoke in accents clear and still. Julie whom I sometimes stood behind in assembly admiring the clean symmetry of her neck muscles and the confident hang of her pony tail.

Oh let me see Thy footprints and in them plant mine own.

My hope to follow Julie is in Thy strength alone.

Outside the hall our teacher told me that my act would have serious consequences. Very serious consequences.

‘You will be banned from country dancing lessons from today onwards!’

Banned.

‘You will certainly not go to the country dancing county championships at Castle Carey in the summer. Everybody else will be going and you will be staying behind’.

The county championships.

‘And I want you to come and see me at the staffroom at the end of afternoon playtime when I’ve had a chance to talk to the other teachers. Do you understand?’

Trembling inside and with my feelings hollowed out, I waited through the afternoon fearing the cane or the slipper. But instead, it had been decided that, while the rest of my class danced after lunch each Tuesday, I was to be Miss Chamberlain’s sole companion in her classroom where I would write lines in silence and help her to make the teachers’ tea before playtime.

I was ten and had never before made a cup of tea, at least not one that was drinkable. All I knew was that a procedure known as warming the pot was key. My mother gave me lessons at home while I implored her not to tell my father what we were doing or why.

Miss Chamberlain was an imposing woman who, in summer, wore large and shapeless floral print dresses. With a pronounced, masculine jaw she reminded me of Desperate Dan’s wife. Her stoical manner suggested that she might not be the most popular of staffroom colleagues and the prospect of having to spend a weekly three quarters of an hour together, just her and me, was a worrying one. In the event, however, although she hardly spoke during our first session we seemed to find a comfortable distance as we pursued our separate endeavours. She was not unduly abrupt about my lack of competence when we made the tea in a large, aluminium teapot and as the weeks passed I settled into a relaxed and almost reassuring routine with her. Two outcasts going about our duties.

Removed from practice for the county championships, far away from the bright white plimsolls, the straightened socks, freshly-ironed white shirts and school ties, I was able to draw strength and a sense of engagement from a very different music caught occasionally on our radio at home – Bill Hayley, Elvis Presley and Chuck Berry.

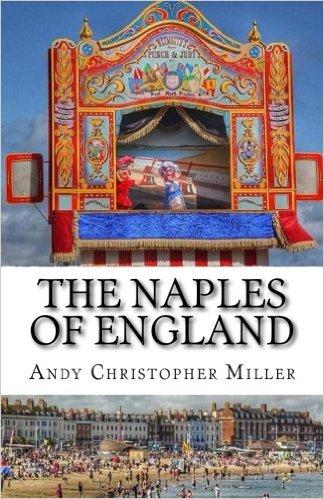

Next week Chapter 8 Pecking Order and Chapter 9 The Naples of England

If you would like to buy the book click here.