BY ANDREW CHRISTOPHER MILLER

Chapter 8

Pecking Order

When I was nine years old my father surprised me by agreeing to the conversion of half of our shed into a pigeon loft, an action forbidden under the terms of our council tenancy. The shed was partitioned with wooden struts covered with chicken wire and into the roof a ‘trap’ was fitted whereby bent lengths of strong wire allowed entry into the shed from the outside but no return.

The true wonder of this shed, however, lay in the homing instincts of its occupants. Other kids gave me pigeons from their families’ sheds and I soon established my own collection of five blue bars and one red. I was told that they would probably ‘home’ after being in their new coop for around three days and, despite fearing ridicule for my lack of patience, I risked my flock to the sky after two and a half. Not just to the immediate space where sunshine and light winds played against our own red brick walls, not just the line of rooftops curving away as Cheviot Road bent gently up hill, but to the whole sky, as vast as the estate and the town, and the open boundaries of the sea and hills that contained my sense of human scale and home.

And they came back. Although I had shaken the corn tin, whistled and called while they executed their swift, swerving patterns between the houses and their joyous high arcs against the blue sky, I knew they returned of their own volition. Some perched on rooftops overlooking the shed for a while, others delayed on the board outside the trap, jerking their heads back and forth. But they all stepped through the trap, the zinc-coated prongs rising across their shoulders as they entered, then falling shut with a thin clank behind them. I showered them with the corn mixture, spraying their floor with my gratitude. Their freedom and captivity, my beneficence and control.

The greatest event though, something which seemed unsurpassed in my life, was the presence one morning of two white eggs in a clumsily constructed nest box. The slightly-built hen bird sitting on them seemed more alert than usual, and I willed these eggs to hatch, knowing from other boys that patience would be required for a full twenty one days.

When had these been laid? Whilst I was asleep or indoors eating a meal?

Despite every warning about disturbing the nest too much, I checked these eggs for fractures a number of times a day, at breakfast time, after school and before going to bed. When a small chipped crack did eventually appear at the apex of one egg, I returned it quickly to the nest, but was back in the shed early the next morning. The crack had developed into fault lines forming three sides of a tiny, ragged square. I held the egg, willing the moment when this tiny trap door would creak open. I imagined my own limbs being folded and aligned, compacted inside exact curved surfaces. Suffocation and terrible constraint. Too tight to breathe, too tight to lever any force against the wall. And then I snicked away the flake of shell with the nail of my little finger.

Horrified at having interfered, instead of a chick bursting with a swagger, beak first out into the open, in the tiny aperture I could see only membrane and pink, under-prepared life. I placed the egg straight back with the other, asked the mother bird to return to the incubation and waited at the door until she did. After running home from school at the end of that day, I felt huge relief at seeing a much larger hole and a yellow beak, new and shiny like plastic, and I left well alone. By the next morning, the baby bird, with sealed eyes and heavy clumsy beak was half out, sitting in the remaining shell as if its broad bottom were wedged inside the bowl.

Both eggs hatched, and nothing in my days equalled the thrill of watching the industry of both parent birds, back and forth, filling their crops with food and regurgitating it into the open beaks of their offspring. Whilst the other pigeons strutted on their perches, even squabbled occasionally over ascendancy, and took the flights I offered them, this all now seemed perfunctory. The up-turned beaks, the screeching at the approach of the parents, the unconsidered purpose in the short repetitive journeys, these seemed to me the obvious priorities of the community.

Almost from hatching, one chick grew bigger than the other. Blind, with only rudimentary stubble where their feathers would grow, their lumpy bodies were more fluid than flesh. The larger bird, at first, had the air of a protective companion, as both were squashed beneath the nesting mother’s feathers or were left looking out into the loft, awkward and lost, while their parents flew or fed. But within the nest box itself, a pecking and trampling order was quickly established. As soon as a parent bird alighted on the edge of the box, both necks extended upwards, straining and crying. But as they struggled, the larger bird more and more frequently pressed down on the other in order to stretch higher. Its creased and elderly-looking legs belied their dispassionate strength, the scrawny, elongated toes and their developing claws, gaining purchase wherever planted, on the body, neck or face of the other. And the parents continued to supply the most prominent beak.

After a week or so, the smaller chick, an albino beautiful with all white feathers, was showing signs of weakening. It asserted itself less and less when a parent arrived, fell beneath the tread of the other more quickly, even looked as though its neck had less strength in the struggle for the food. I removed the larger one at times and held it in my hands, hoping the other would thrive if allowed occasional, exclusive access to its parents. But this made little difference. Sustenance of a more fundamental nature was missing. Each time the claws descended and its face was pushed down into the straw, each time both parents continued to disgorge the contents of their crops automatically into one beak but not the other, the hideous differences between the two chicks grew. I tried removing the albino and feeding it milk through a pipette from my chemistry set. Its neck and wings seemed slack and unable to compose themselves. It seemed reluctant to open its beak, it choked and was unable to retain much of the milk. Back in the nest box, there was no alteration of routine among any of the birds, no compensations, no recognition.

‘It’s dying’. ‘It’s had it, y’ better ring its neck’. Other kids offered their advice, and I listened especially to those with older brothers whose worldliness I admired. ‘Do you know how to?’ ‘It’s dead easy’. ‘Our Malcolm will do it if you can’t’.

‘All it needs is food, and not to be trodden on all the time’. I knew this but had been unable to have the slightest effect on the course of its decline. My parents did not know what to do either. I wanted to kill the bird myself, to do it swiftly and carefully, to be in contact with it when it died. The procedure had been explained to me, I held it as I would a larger bird, my forefinger behind the legs, the other three in front cradling the stomach and restraining it, my thumb across its back. The small, slack body almost oozed between the gaps in my fingers. I knew what I had to do, place the first two fingers of my other hand either side of the neck then firmly and definitely, twist and pull at the same time. One turn, at least a quarter of the way around, further would be better. I felt its neck, the hopeless lack of strength, no sense of bone or structure for me to definitively crack and break. I was determined to be the executioner, to submit its body to one brief, last act of violence and free it from the daily round of humiliation and abandonment back in the loft.

Pull and turn; pull, twist and turn. I muttered the manoeuvres, holding the flaccid body and rehearsing. I was almost ready, one tiny instant away. Twist, snap, and pull, the baby bird’s death groan, a saddened gargle of bubbles in the throat or a frantic final wheeze of breath. Twist and pull.

What if I failed, made half a move and then panicked, desperate to repair the destruction? What if I did all I was supposed to do, and it still didn’t die but instead the neck, more hopeless still, just dangled further down the body? I couldn’t do it. Pull, snap, done. I could not carry out this one quick, efficient act and become grown up – decisive and compassionate and unafraid.

My friend said his father, who kept pigeons himself, would do it that evening when he came home from work. I made further futile attempts with the pipette and it was still alive as I walked up later, alert to the rows of vegetables in the back gardens and a radio letting slip a pop song through an open window. I handed over the box feeling abject and not able to say much. He saw it in me and said ‘Leave it with me, son. I’ll take care of it when I’ve had my tea’.

Chapter 9

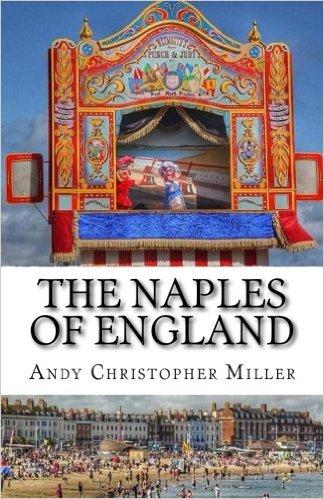

The Naples of England

The people of Weymouth, attentive to the horizon like predators weakened through a long winter, would muster their depleted energies during the first stirrings of Spring.

‘They’ll be flocking in if this weather keeps up’.

Shutters and awnings rattling, dust beaten out, accumulated pockets of sand swept from doorways, council vehicles parked up on the empty, pedestrians-only promenade. The clatter from lorry loads of deckchairs out of winter storage and being built into stacks on the beach. Canoes nestling like sardines. Huge floating craft across the backs of youths, their arms splayed as if in crucifixion, carried down to the water’s edge. Narrow strutted jetties wheeled into the sea, prodding the retreating nip of winter still residing in the sea’s temperature.

In the clear, exacting focus of a new season’s light, beach stalls creaking open, crockery clinking and cups chattering in wire trays, urns subjected to trial runs with bulky masses of steaming water, serving hatches prising open, chalkboards brought out into the daylight, rows of hooks weighted down with joyous trivia. From rooftops, balconies and empty, stale interiors, the broken orchestration of hammer and saw, fresh resin and the heady musk of tar and paint. All in preparation for the silver shoals, the flocks alighting, the herds stopping to graze. Survival and restoration, appetite and livelihood.

My father would be out shopping in the town centre on summer Saturday mornings as early as he could.

‘If you’re not done and home before ten, you might as well forget it,’ he would say.

We took in summer visitors, factory workers and their families from the West Midlands, women and children from South Wales with their huge men who hewed the coal there. ‘As long as they don’t start singing,’ my father once said, never completely happy with the opening up of our house in this way. My mother advertised in Daltons Weekly and selected regional newspapers. A neighbour had inducted her into the procedures but she secreted away what she believed to be the winning words with which she had constructed her three-line classified advertisement. This was the only way we could afford a holiday, my mother said, ‘working my ruddy fingers to the bone,’ fried breakfasts every morning carried on a tray into our best front room, sleeping arrangements in weekly flux, my box room the first to be requisitioned. Once I shared the pull-out sofa bed with my mother for the only time it was ever used. And on another occasion my father and I were in the kitchen on camp beds that had to be dismantled and packed away by 7.15 ready for him to shave at the sink and then for her to scramble pots and utensils ready for the daily conflagration of bacon, eggs, tomatoes and sausages.

Sometimes families were split between neighbouring houses, pot luck holidaying among the empty or vacated rooms along Purbeck Road. Others occasionally arrived unannounced, on the off chance. Their cases would be brought discretely inside our privet hedge and the people left standing in the garden, while my mother worked her way along the neighbouring doors, permutations being reckoned and resolved in the emergency negotiations. Sometimes there seemed to be transfers after dark, movement between safe houses. And whoever was found a bed, whatever their pairings or combinations, they were to be without trace on Tuesday mornings when the council rent collector made his rounds, for fear that he might note any tell-tale irregularities, clues to contravention of our tenancy agreements.

As a child the physical appearance on maps of my home town and its surrounding coastline gave me a thrill each time I saw it. The Naples of England. That was what people called Weymouth, my father told me, because of its perfect bay. I took pride and pleasure in this.

Our town was situated at the meeting point of two huge tracts of water that curved in from opposite directions. To the east, the direction that our seafront hotels and esplanade faced, was Weymouth Bay, a perfect arc of golden sand leading first northwards and then round towards deserted, inaccessible cliffs and headlands that on fine days – and most were fine days – we could make out dipping and rising all the way to exotic destinations such as Durdle Door and Lulworth Cove. At the southern end of the town’s beach, where the gently shelving sands dipped into a sea that seemed especially warmed in the bowl of the bay, was the Pleasure Pier which formed one of the two arms protecting the entrance to Weymouth Harbour.

And in the harbour, the ferry boats, passengers embarking to the Channel Islands, huge crates of tomatoes obscuring the sun as they were swung by cranes from the decks of cargo ships down towards us watchers on the dock. On still summer nights lying in bed a mile away in Purbeck Road I could hear the boat train clanking along tracks down the centre of Commercial Road carrying its passengers from the railway station to the waterside or screeching and grinding to a halt at some obstruction. If they passed us during the day, stopping the traffic, we could look up at the people in the carriage windows, sitting self-consciously looking down at us. With us but not of us, like the thousands who covered our sands at the height of the season.

Across the harbour, towering above the Stone Pier, was the Nothe Fort. From the ornamental gardens beside the fort, one could look in one direction down into the harbour and on towards the Pleasure Pier, sands and seafront. In the opposite direction was Portland harbour, battle grey ships, breakwaters with tiny lighthouse buoys, gates and railings and padlocks, access restricted to naval personnel, and then, throwing it all into scale, the huge bulk of Portland squatting in the sea some five miles away.

Along the Pleasure Pier, a huge platform with pontoons sunk into a dark and sunless sea, holidaymakers paraded in their numbers. My parents had met in their youth through the Swimming Club out at the end of this pier. I could just pick them out among the smiling young people, some tentative, others more defiant and self-assured, staring out from the old photograph. Ignore the hair styles and bathing caps, the one piece costumes. Ignore a war looming across Europe, and those faces in the strong summer sunshine could be looking out from the 1960s.

As the sands curled around to meet the Pleasure Pier, about a quarter of a mile from the Nothe gardens, there were the donkeys. When I was young, there was no greater treat than to ride in procession down the sea’s edge on one of their backs. The warm, sweet smell from the dung dropped outrageously onto the sand, the creak and resinous scent from the saddle as I shifted position, the hardened bony back beneath the sparse wiry hair, all gave rare textures to being alive.

Right beside the donkeys, the sand modeller’s enclosure, Frank Dinnington sculpting huge versions of Salisbury Cathedral, every transept, spire and window precisely fashioned. Or, the tableaux of the Last Supper, Jesus and the disciples, rounded shoulders and compassionate foreheads, their bodies leaning in towards each other. ‘All made entirely from local sand and water,’ said the scrawl on the board, and the pennies, threepenny and sixpenny bits trickled down from the promenade into the collecting buckets. Every so often, regularly it seemed, the local paper would carry a photograph of a collapsed cathedral wing, a mighty structure reduced to sand, and a story headlined something like ‘Smashed by vandals’. And the coins would flow in a heavy torrent.

A further one hundred yards or so along the sands, you would reach the First Aid and the Lost Children’s huts, a pair of semi-detached white painted wooden huts with an enclosure formed by a white picket fence. These dispensed disinfectant, ointments and a sense of protection.

Most summers we holidayed at home, or rather my brother and I ran full bodied between the thousands grouped in deckchair communities, squeezing between their encampments, in and out of the warm shallows, a whip of bladder wrack, if one could be found, lassoing the air.

‘Be careful what you’re doing with that around people’s faces,’ my mother might warn.

‘Look out for that yellow dinghy,’ or something similar she would explain so that we could eventually find our way back to her deck chair. ‘And if all else fails go to the Lost Children’s Hut’.

Another visitor attraction – why would we ever want to travel any further into England? – was the tall thin box painted in red, white and pale blue stripes, Frank Edmunds’ Punch and Judy stall. Taking my penny for the collecting box as often as I could afford, I would ease my way in amongst all the visiting children who chanted when required or instructed. Singing through reeds or his huge curving nose, mad-eyed Mr Punch, with his stick to his shoulder, surveyed all below him seeing with a long, lingering look into each of our deceitful hearts.

‘Judy, where’s the baby?’

‘Downstairs’

‘Bring it up, bring it up’.

‘OK, here’s the baby’.

Thwack, thwack, thwack.

‘That’s the way to treat the old lady’.

One set of guests registered more than most with me when I was nine years old. A young couple, Paul and his fiancé, Marion, stayed one summer with his parents, occupying all three of our bedrooms A red haired, tubby and boundlessly enthusiastic young man, Paul asked my parents if I could accompany Marion and him on a fishing trip so that they could benefit from my knowledge of the choice locations. They also took me with them to the Fair. As much as the fishing, the Fair, the ice creams and the candy floss, I especially enjoyed evenings in our front room, which my parents had designated the ‘visitors’ lounge’. Just the three of us, Paul, Marion and myself while his parents went out, with me enlivening their stay with animated tales of local life.

‘You can’t keep going in that front room,’ my mother said, oblivious to the camaraderie we shared. ‘They’ve got to be allowed to have a bit of time to themselves’.

The next spring I was delighted when Paul wrote to my mother asking if they could again book a week’s stay in August. But her manner clearly showed that she did not share my sense of joy.

‘That Paul from Wolverhampton wants to come again, in August, peak season, with that fiancée of his,’ my mother told my father when he arrived home from work that evening. ‘Just the two of them’.

‘Great!’ I replied before my father could answer. ‘They can, can’t they?’

My mother waved the letter in an erratic fashion as if she was trying to shake it from her own grip.

‘Says they just want the one room,’ she added.

‘I told you this sort of thing would happen when you started all this,’ my father snapped. ‘You’ll have to write and tell them you’re fully booked.’

‘But we’re not,’ I said. ‘Mum said so.’

My mother held my father’s gaze, ignoring me.

‘But why can’t they come?’ I persisted.

‘They can’t and that’s that!’

‘But why?’ I asked one more time although I knew that by now the outcome was firmly settled.

Next week Chapter 10 Like Survivors and Chapter 11 Only a Book

If you would like to buy the book click here.