In the century since 1914, The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists (RTP) has had 117 printings in the UK, plus one braille version, 15 printings in Canada, Australia, the USA and Russia, and translated printings in Russian (3), German (6), Dutch (2), Polish (2), Slovak (1), Czech (1), Bulgarian (reportedly) (1), Japanese (1), Persian (1), Chinese (2), Korean (1), Turkish (1) and Spanish (1), plus several often inaccurate and overpriced print-on-demand versions in English, and various plays, radio programmes, TV films, tapes and CDs. Most book-publishers will not disclose their print runs, yet several million copies of RTP must be in circulation, but why?

Generations of workers have taken the book to their hearts and it is one of the most frequently loaned books of all time. True, it was the first lengthy account of how capitalism operates at the point of production, from the point of view of a skilled British worker, and it has humour, parody, pathos, irony, rage, little victories, defeats, arguments and ideas; but while it is brim full of hatred and contempt for the capitalist ‘System’, the ruling class and their hangers-on, it is very hard on workers, and it is not quite as realistic as ‘Robert Tressell’ claimed.

Understandably, Robert Noonan used a pseudonym to protect his identity and he set his story in ‘Mugsborough’, ‘a small town in the south of England’, though its coordinates of ‘about 200 miles from London’ and 100 miles from the coast would put it near Milford Haven in South Wales! However, why was Mugsborough’s climate different to the rest of southern Britain, since winter takes up three-quarters of the year, and where are the sea, the beach and the holidaymakers? Where are the author’s fellow Irishmen and women, the people who built Victorian and Edwardian England, and the recent workers’ victories, like those of the ‘match girls’ in 1888 and the dockers in 1889? Why does RTP highlight the bloody defeat of strikes in Featherstone in 1893 and Belfast in 1907, but not the massacre that sparked a revolution in Russia in 1905, and where are the past political struggles in Sussex, including ‘Captain Swing’ and the Chartists? Above all, where are the Hastings suffragettes, the nationally-famous trade union activists, like the docker, Ben Tillett, who ‘Tressell’ may well have heard speak in Hastings, and where are Mugsborough’s organised trades unionists and socialists?

Frank Owen, the nearest person to a ‘hero’, is ‘one of the damned’ from the start, because of his poor health. He rarely mentions the ‘Society’ – the painters’ union – or the Trades Council, while male workers give the liberal ‘Dr Weakling’ the ‘dirty kick-out’ in the council elections and they discount ‘Them there Labour members of parliament’. Owen patronises his workmates and is arrogant. When one tells him that ‘you think your opinion’s right and everybody else’s is wrong, Owen says ‘Yes’, and his response to ‘wot do you reckon is the cause of poverty, then?’ is abstract propaganda.

The present system – competition – capitalism … it’s no good tinkering at it. Everything about it is wrong and there’s nothing about it that’s right. There’s only one thing to be done with it and that is to smash it up and have a different system altogether.

Yet when the foreman cuts the less skilled workers’ wages by from seven pence an hour to sixpence halfpenny downstairs, Owen carries on doing skilled work upstairs at eight pence an hour. Owen was well aware that ‘People always take great care of their horses’, but effectively tell employees to ‘Submit or Starve, Eat dirt, or eat nothing’, yet Owen blames the workers.

As Owen thought of his child’s future there sprung up within him a feeling of hatred and fury against the majority of his fellow workmen … They were the enemy! They were the real oppressors! …They were the people who were really responsible for the continuation of the present system … No wonder the rich despised them and looked upon them as dirt. They were despicable. They were dirt. They admitted it and gloried in it.

Owen tells himself that they are backward: ‘willing to oppose with ignorant ridicule or brutal force any man who was foolish or quixotic enough to try to explain to them the details of what he thought was a better way’. They are ignorant: ‘Our children is only like so much dirt compared with Gentry’s children’. They are plant pots for capitalist newspaper propaganda: ‘seeds … cunningly sown in their minds, caused to grow up within them a bitter undiscriminating hatred of foreigners’. They are mad: ‘If these people were not mentally deficient they would … have swept this silly system away long ago’. Some are depraved. The horse-drawn carriages full of ‘drunken savages’ taking the workers to and from the annual ‘Beano’ are like ‘so many travelling lunatic asylums’. Evidently, there is no hope for ‘the likes of us’ on Planet Mugsborough, so ‘Truly the wolves have an easy prey’. Eventually, in comes Barrington, a wealthy outsider, who tells his workmates that ‘you must fill the House of Commons with Revolutionary Socialists’. Yet he assumes that the state is a neutral machine and that democratically elected revolutionaries could steer society towards socialism, through reforms, unmolested by capitalists, the armed forces, the judiciary, the civil service and the Established Church. Yet when a renegade propagandist shakes his faith in the working class, all Barrington can think to do is to fit out another propagandist ‘Socialist Van’. RTP was close to the cutting edge of reformist socialist thought in 1910; but it was not revolutionary in a Marxist sense. Almost all of Marx and Engels’ works were unavailable in English, except for a few imported from Chicago, and Noonan may well have taken ‘The Great Money Trick’ from a visiting speaker from the reformist Independent Labour Party. Like Noonan, Tommy Jackson was a member of the Social Democratic Federation, though he later joined the Communist Party and recalled that his SDF comrades had

thought their duty done when they had told the workers with reiterated emphasis that they had been and were being robbed systematically, and given them an exposition of how the trick had been worked. From this the workers were to draw a moral conclusion that the robbers ought to be stopped, and to reach a practical decision to wage a class war upon the robbers. When their audience didn’t reach this decision … [SDFers] Here wont to conclude that ‘the bastards aren’t worth saving’.

Of course, ‘Tressell’ was not Lenin – who had only 20 émigré intellectual supporters in Switzerland in 1910 – and Noonan died in Liverpool in February 1911. Yet in August, after the revolutionary syndicalist Tom Mann agitated 100,000 workers outside St George’s Hall, just down the road from where Noonan died, police charged repeatedly and injured and arrested many. After 3,000 workers tried to free those being taken to Walton Goal, troops shot and killed two of them. A city-wide strike began and the ‘Great Unrest’ was underway.

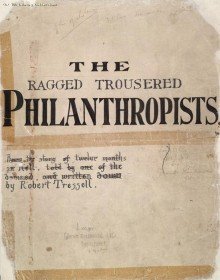

In 1913, Noonan’s daughter, Kathleen, was a servant in London, and showed her father’s manuscript to her employer. She asked Jessie Pope, the well-known writer for Punch, to read it, and she convinced Grant Richards to publish a shorter version. By spring 1914, Pope had cut around 110,000 words of what she called ‘surplus matter’ from the 300,000-word manuscript, including much of the socialist propaganda. She also renamed the author as ‘Tressall’ and ended the book with Owen contemplating suicide. On 23 April, Richards published it in London at six shillings – around two days’ pay for a male industrial worker and four days’ pay for a woman – and he had to reprint it in May, when there was also a New York edition; but British sales ‘died’ in August, as many Western European trade union and reformist socialists abandoned their former internationalist rhetoric and got behind their ‘own’ ruling classes in the ‘Great War’.

After the Russian Revolution of October 1917, and years of imperialist slaughter, some socialist workers in Britain cottoned on to the propaganda potential of RTP, and just before the war ended in 1918, Richards published a one shilling version – under a day’s pay for a male industrial worker, but twice that for a woman – for the working-class market. What one reader called ‘Pope’s bloody mess up’ included only 90,000 words, and Owen still contemplated suicide at the end, but it sold well.

By 1926, when union leaders were terrified of offering a winning strategy in the General Strike, the 1918 RTP was in its fourth printing; and by 1931, when Ramsay MacDonald, the first Labour Prime Minister, helped the Tories make workers pay for capitalism’s crisis, three more printings had appeared. Soon after, when Hitler came to power in Germany, many British socialists joined the Communist Party, and in 1935, as Stalin moved rightwards towards a Popular Front perspective, and then began murdering around one million ‘enemies of the people’, including most of the Bolshevik leaders of 1917, The Richards Press (which Richards no longer controlled) reissued the 1914 RTP. In 1940, Penguin published the 1918 edition as a paperback for sixpence – around half an hour’s pay for a male industrial worker, but twice that for a woman – and The Richards Press carried on reprinting the 1914 edition. From 1941, after Hitler broke his pact with Stalin, and Russia joined the capitalist Allies, British Communists and Labour left-wingers pushed the Penguin RTP in the armed forces and trade unions, and it was in its fifth printing by 1944. Reportedly, sales were massive, and the book contributed to the Labour Party’s landslide election victory in 1945; but the Labour cabinet went on to make an economic and political alliance with the USA, carried on with rationing and sent troops to break dockers’ strikes, so the Tories got back into office in 1951.

In 1955, just before Stalin’s crimes were acknowledged in Russia, and after years of dithering, the British Communist Party publishers, Lawrence & Wishart, issued Fred and Jacqueline Ball’s reconstructed version of the RTP manuscript. A ‘De luxe’ hardback of this ‘complete’ edition cost £1.10s. – around £33 at today’s values, and the highest ever price in real terms – and 10s.6d., or two hours’ pay for a male industrial worker and twice that for a woman, for one of the 3,500 copies of the ‘limp’ ‘Special Trade Union Edition’. In 1965, when the Lawrence & Wishart version had had its third printing, Panther published a paperback of the 1955 edition for 6s.3d., or around £5 at today’s values, and RTP became part of many trade union and socialist propagandists’ ‘tool-kits’.

The book offered a socialist critique of some of the key ideas that seek to justify class society, and it rarely let the bosses and ‘Idlers’ off the hook, but while it retained a rhetorical faith in the coming Co-operative Commonwealth, it did not tackle (let alone solve) the problem of how to get there. Some Mugsborough workers get ‘some of their own back’, some of the time, yet the book stressed that do-it-yourself reforms were temporary and that unorganised workers were powerless against bosses, and while it exhorted workers to ‘Blame the System’, the odds were stacked against them.

A few supercilious individuals have argued that RTP appeals to isolated workers, mainly in periods of working-class defeat, because of its ‘pessimism’ and ‘elitism’; and yet most of the negative outbursts about workers are not speeches by the socialist characters. Instead, especially after they have won an argument but made no converts, the narrative voice ‘reports’ on how they deal with their frustrations ‘privately’, sometimes in bitter monologues, but usually by rehearsing previous dialogues with workmates. In the 1920s, Valentin Volosinov argued that this ‘dialogic’ technique was an effective way of representing ‘class struggle in the head’, and RTP targets the heads of readers, so almost every page encourages us to take sides in the dialogic arguments.

Today, workers face the same political choices as those in 1914. Do we give in to ‘sophisticated’ despair, blame others for their gullibility, convince ourselves that they cannot change and settle, at best, for a few crumbs from the capitalists’ table? Or do we carry on, like Owen and Barrington, patiently explaining how the ‘Great Money Trick’ works, but, unlike them, go on to organise fighting unions and build a fully democratic socialist party, rooted in the working class, which may try to send revolutionaries to Parliament for propagandist purposes? RTP continues to offer readers this fundamental choice and so it remains highly relevant to ‘the likes of us’, as we struggle to put socialist ideas into practice in the 21st century.

Dave Harker

Dave is the author of Tressell: The real story of The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists (London: Zed Books, 2003. Manila: Ibon Books, 2004).