Russell Brand is the guest editor of this week’s New Statesman, The Revolution Issue. Brand’s own contribution to the magazine, a 4,500 word polemic on the state of a political system that serves a very few at the expense of the rest is recommended reading.

Brand’s essay was impassioned, righteous fury aimed at a broken system. More poetry than prose and full of uncomfortable truths and high ambition.

Brand wants a “genuinely fair system”, and I’m delighted to hear he would be prepared to give up some of his “baubles and balderdash” in order to get it because that means we can’t call him a hypocrite.

A genuinely fair system, Brand says, requires us “to be inclusive of everyone, to recognise our similarities are more important than our differences and that we have an immediate ecological imperative.”

His optimism for achieving ‘utopia’ is premised on his ”knowledge that this total social shift is actually the shared responsibility of six billion individuals who ultimately have the same interests. Self-preservation and the survival of the planet.“

As far as I can see this is every reason to be pessimistic. Is this not Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons writ large? As individuals we each act according to our own self-interest, even though we know that depleting the shared resources the planet is at odds with the groups’ long-term best interests.

Brand argues that we have a political system that “no longer represents, hears or addresses the vast majority of people”. Yet, ’people’ resist simple binary division into those who are served by the system, and those who are not. What is more, even if six billion minds were on the cusp of a collective ‘revolution of consciousness’ they would not share a common conception of Utopia, let alone Brand’s version. Twenty-five centuries of political thought has failed to produce a consensus on the nature of ‘the good life’.

Neither, do I agree with Brand that we are all apathetic. Let us not forget, it is still the case that more people vote than do not and our national civic life is alive, if not positively vibrant, with social action. It is simply untrue to say “most people do not give a fuck about politics”. Colin Hay argues in Why We Hate Politics that we don’t hate ‘politics’ at all, rather it is the politicians we’re not fond of. We increasingly see them as self-interested. Whilst we have become irritated or outraged by the political process (Newsnight, that forum for unedifying political debate, is a case in point) we are not apathetic.

Brand chose the theme of revolution for the New Statesman because, “imagining the overthrow of the current political system is the only way I can be enthused about politics”. Well, imaginary it must remain. ‘Most people’ do not perceive their interests to be in common. ‘Most people’ do not share a vision of ‘the good life’. There can be no revolution.

WE have lost confidence in our democratic political culture, that is if we ever had it. I wonder if complete satisfaction would give us equal cause for concern? In short, society changes, and the political process will forever be behind the curve. In the scrabble to appeal to the ‘middle voter’ politics has become less conviction-oriented. ”Today, it is no longer enough to manipulate, transport, and refine belief; its composition must be analysed because people want to produce it artificially; commercial and political marketing studies are still making partial efforts in this direction. There are now too many things to believe and not enough credibility to go around.” says de Certeau. A cynical public sees promises made today and broken tomorrow.

Parties have been sidelined as we have become ‘consumers’ of good causes. But what other than a political party can aggregate all of our diverse interests into a coherent political entity?

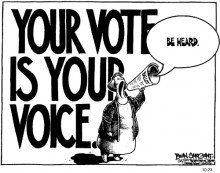

I suggest there has never been a greater need for representative politics and therefore for the politicians themselves. Renounce the system and don’t vote, says Brand. But British general elections are won or lost on a handful of marginal constituencies where staying at home can make a real difference to the outcome. Brand makes the mistake of believing that voting and revolution are mutually exclusive. They are not. We can and must seek fundamental reform of the system.

But do vote. There will be no revolution but there will be many elections.

Alison Smith