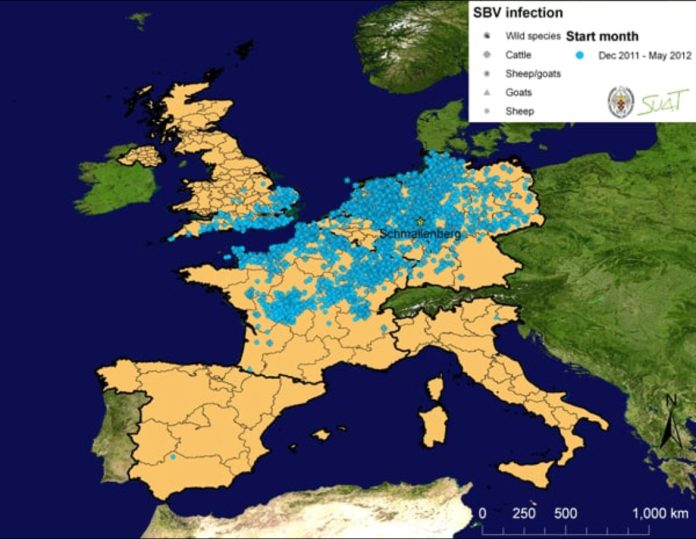

In August 2011, a mysterious disease appeared in adult cattle in the west German town of Schmallenberg, situated some 70 miles east of Cologne and hitherto best known for its textiles. From there, it spread into Holland and Belgium. Initially manifesting as fever, loss of appetite, reduced milk yield, and occasional diarrhea lasting for a few days, by November it became apparent that afflicted animals, which included cattle, sheep, and goats, were giving birth to young with severe deformations of the limbs, including fused joints, and damage to the nervous system. Many such animals were stillborn. The adult animals themselves usually make a normal recovery with no lasting effects, although the loss in body weight and reduced milk yield reduce their value.

By December 2011, it was apparent that a novel virus species was involved, and it was placed putatively in the genus Orthobunyaviridae. This is a large group of viruses, containing some 170 species, most of which are spread by biting insects and which cause diseases of cattle. Hitherto, probably the best known virus in this genus was La Crosse virus (California Encephalitis Virus) which is spread by a mosquito vector, and causes encephalitis in children and forestry workers in wooded areas of the United States.

Schmallenberg virus in the United Kingdom

On 22 January 2012, it was confirmed that the virus had reached the United Kingdom and was formally identified on four sheep farms in Norfolk, Suffolk, and East Sussex. By 27 February 2012, the disease had been reported on the Isle of Wight, Wiltshire, West Berkshire, Gloucestershire, Hampshire, and Cornwall, all in the south of England. It is considered likely that the virus was carried from mainland Europe to eastern England by midges, probably during the autumn months. This is also the mechanism by which the bluetongue virus (of sheep) arrived in the UK in 2007.

Could the Schmallenberg Virus be transmitted to humans?

Scientists at the Robert Koch Institute, Germany, have been monitoring sheep farmers and so far have found no evidence of the Schmallenberg virus being passed on to them, although some have reported such non-specific clinical symptoms as fever and cold-like symptoms. Since, as has been explained above, a small number of Orthobunyaviruses are zoonotic (capable of transmission from animals to humans), scientists from the Netherlands RijksInstitut voor Volksgesondheid en Milieu (RIVM) have carried out a risk analysis and concluded that transmission to humans is unlikely, although, of course, it cannot be excluded.

Midges

Research has shown Schmallenberg Virus to be present in midges of species Culicoides dewulfi and C. obsoletus, collected in Belgium, Denmark and Italy. These are biting midges.

In the following extract available on the internet, Dr Doug Wilson, a vet from Bristol, describes how a midge bites a horse:

“After alighting on a horse, midges crawl down the hair shafts to the skin surface. Their mouth parts are too short to probe for a blood vessel like their larger cousins, the mosquitoes, so they have to chew their way through the tough outer layers of skin.

To assist their efforts, they secrete saliva containing a mixture of enzymes that digest and soften the skin tissue as well as agents to encourage extra blood to flow to the site of the bite and several factors that will prevent the blood clotting. A small pool of blood forms just under the skin surface and is then sucked up by the midges.

The whole process takes about 15-20 minutes and, over the course of an evening, a horse may be bitten by hundreds or even thousands of midges, each one injecting a small amount of saliva containing foreign proteins into the horse.”

This is also the process by which viruses could be transmitted to an animal

Midges are attracted by carbon dioxide gas exhaled during respiration, and by other chemicals released from the skin, and can detect an animal from a range of up to 100 metres. It is estimated that a swarm of midges can deliver approximately 3,000 bites an hour.

The present situation

To date (13 April, 2012) Schmallenberg virus has still not spread beyond the south of England and is still restricted to the North West of Europe as a whole.

Interestingly, however, scientists from the Friedrich Loeffler Institute in Germany have reported finding antibodies to Schmallenberg Virus in both red and roe deer. This could be of interest to those of us living in close proximity to the New Forest, which contains five species of deer.

The three counties most severely affected in the UK are East Sussex, West Sussex and Kent, all with just over 40 farms affected. Dorset is escaping very lightly, with only 5 farms, and only sheep being affected. The situation has been stable since the end of April.

Alan Crooks